Drama Tuesday - What is distinctive about Drama teaching!

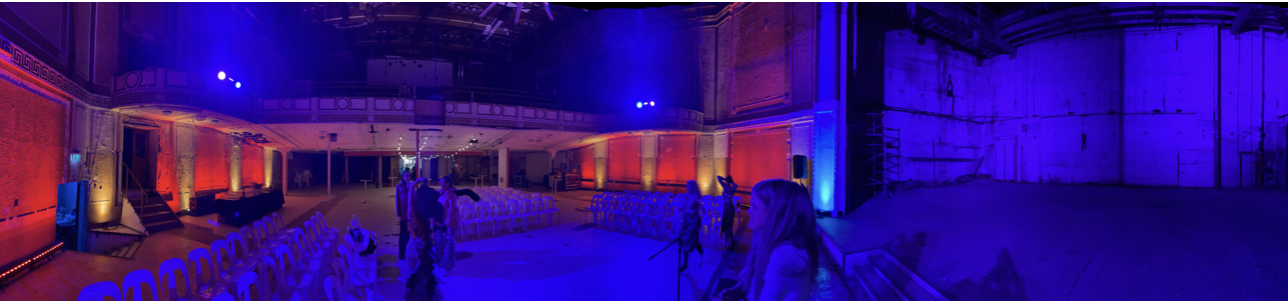

/From time to time in reading research you find succinct encapsulations of what we do as drama teachers. The following comes from an article by Coleman and Thomson (2021) in a discussion and reflections about an experienced drama educator who recently transitioned from the drama space she ‘made do with’, into a purpose-built ILE (Integrated Learning Environment) school.

In the opening sections, as good researchers do they declare their positionally.

Positioning Our Pedagogy

We approach teaching and learning in the arts and the generation of knowledge as a shared responsibility between students and teachers. This sociocultural approach emphasises the significance and development of the social competencies most likely to engage students in creative, flexible learning. Competencies likely to prepare them for the complexities of living in a time of rapid change and uncertainty.

Drama relies upon dialogic and relational pedagogy and the creation of a community of learners. Teaching episodes in drama often involve flexible, active creative processes that invite students to determine and reflect upon their own work. While teachers require curriculum knowledge, it is their ability to foster creativity and criticality in students through this complex human art form, that is of central importance to facilitating drama (O’Connor et al., 2016). As a collaborative art form, drama requires a high level of emotional safety. Participants, through drama, enter into a creative partnership (Eisner, 2002). The alchemy of quality drama teaching and learning rests upon the interdependent and relational nature of these elements.

So many points of resonance for my practice.

They also provide an effective “definition” of drama education which I was particularly taken with. It is a useful echo location beacon for contemporary thinking about our field.

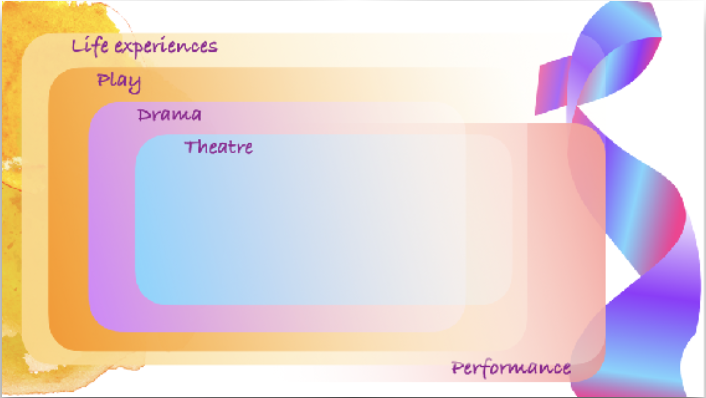

Drama Teaching drama is unlike teaching any other school subject; it is experiential learning involving each of the senses, body language, and emotion and is often a way of engaging students who have been otherwise alienated by the rest of the curriculum (Hatton, 2020, para 9).

Drama in schools incorporates both drama as an aesthetic discipline and as a

pedagogy for exploring and creating. As a pedagogy it is often valued in schools for its ability to engage students with other curriculum areas (Wilhelm, 1998). Drama invites participants to explore complex responses through fiction and employ both their affective and cognitive faculties to engage, resist and act (O’Connor et al., 2016).

As a pedagogy, drama welcomes play and experimentation for possibility thinking and problem solving, aligning it with the current educational focus upon creativity, resilience and flexibility (DICE Consortium, 2010). Educators acknowledge that drama elicits the playful, critical, the collaborative and the opportunity-seeking behaviours essential to the unpredictable future of our twenty-first-century learners (Pascoe, 2015). Drama can activate soft skills and engage diverse learners through integrated learning experiences in an imagined setting (Anderson & Dunn, 2013; Jablon, 2017). As Luton (2016) acknowledges, when drama entered the Aotearoa New Zealand curriculum in 1999 as a distinct subject, a number of schools were unprepared. Years later, drama classes continue to struggle for space, resources and expertise. Despite these hurdles, as an active and embodied medium, drama remains inclusive and accessible to a range of learners (Stinson & O’Connor, 2012).

In Aotearoa New Zealand, drama practice is underpinned by a strong ethic of manaakitanga (the shared values of integrity, trust, sincerity, equity) and ako (to teach and to learn). These two Māori concepts facilitate the shared negotiation of a kawa (etiquette or protocol) and provide a living agreement for praxis (Cody, 2015; Te Kete Ipurangi, 2011). Ensemble building within drama classrooms relies upon the creation of whanaungatanga or sense of family connection. Such a connection is supported by the dialogic relationship of teacher and student, which upholds ako through the provision of a space in which students are valued and validated (Cody, 2015). Enhanced by the physical, drama spaces work towards the ongoing development of learning communities that are democratic, and inclusive in which participants are heard and repositioned learners (Leggett & Ford, 2013).

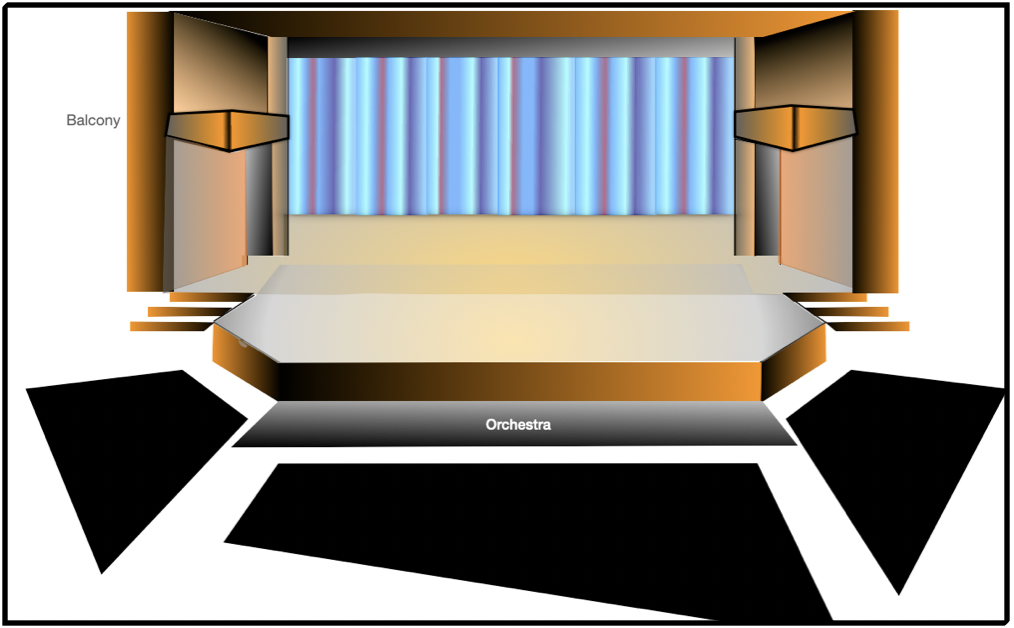

As noted earlier, the majority of Aotearoa New Zealand drama teachers are particularly adept at flexible pedagogy and the challenges of adapting spaces. As detailed by Luton (2021), drama teachers have a greater reliance upon open spaces than others’ and accordingly make space for groups, rearrange furniture, or get rid of it. When teaching the default position of many drama teachers is alongside students in a circle to ensure interactions between both teachers and students (Kariippanon et al., 2017) This provides an embodied commitment to a collaborative pedagogy and the creation of an inclusive, democratic space (Vettraino & Linds, 2018). The drama classroom and its capacity to be open, transient and responsive lends ‘itself to transformation by participants and the teacher’ (Nicholls & Philip, 2012, p. 584).

Absent from the drama teacher’s classroom are the obvious distinctions between the teacher space and student space. As Lambert, Wright, Currie, and Pascoe (2015) explain the drama classroom is one dedicated to students’ becoming and offers a flexible space that can adapt to ‘varied pedagogical approaches and purposes’ (Nicholls & Philip, 2012, p. 586). It operates as a brave space for learning and creating that welcomes the ‘strengths and weaknesses of participants’ (Nicholls & Philip, 2012, p. 584) and is negotiated in partnership (Rands & Gansemer-Topf, 2017).

While there are parallels in the pedagogical strategies of the drama teacher and those advocating for ILE’s, little research currently exists on ILE classrooms and teaching in the arts. Designed to cultivate flexible, adaptable and mobile citizens for the competitive global economy (McPherson & Saltmarsh, 2016) the utilitarian goals of the ILE classroom remain problematic for the arts practices.

Does this resonate with you?

The contextualising for New Zealand is also interesting as Australian educators, take more notice of First Nations ways of thinking and knowing and being.

References

Coleman, C., & Thomson, A. (2021). No Drama: Making Do and Modern Learning in the Performing Arts. In N. Wright & E. Khoo (Eds.), Pedagogy and Partnerships in Innovative Learning Environments. Singapore: Springer Nature.