Drama Tuesday - What is distinctive about Drama teaching!

/From time to time in reading research you find succinct encapsulations of what we do as drama teachers. The following comes from an article by Coleman and Thomson (2021) in a discussion and reflections about an experienced drama educator who recently transitioned from the drama space she ‘made do with’, into a purpose-built ILE (Integrated Learning Environment) school.

In the opening sections, as good researchers do they declare their positionally.

Positioning Our Pedagogy

We approach teaching and learning in the arts and the generation of knowledge as a shared responsibility between students and teachers. This sociocultural approach emphasises the significance and development of the social competencies most likely to engage students in creative, flexible learning. Competencies likely to prepare them for the complexities of living in a time of rapid change and uncertainty.

Drama relies upon dialogic and relational pedagogy and the creation of a community of learners. Teaching episodes in drama often involve flexible, active creative processes that invite students to determine and reflect upon their own work. While teachers require curriculum knowledge, it is their ability to foster creativity and criticality in students through this complex human art form, that is of central importance to facilitating drama (O’Connor et al., 2016). As a collaborative art form, drama requires a high level of emotional safety. Participants, through drama, enter into a creative partnership (Eisner, 2002). The alchemy of quality drama teaching and learning rests upon the interdependent and relational nature of these elements.

So many points of resonance for my practice.

They also provide an effective “definition” of drama education which I was particularly taken with. It is a useful echo location beacon for contemporary thinking about our field.

Drama Teaching drama is unlike teaching any other school subject; it is experiential learning involving each of the senses, body language, and emotion and is often a way of engaging students who have been otherwise alienated by the rest of the curriculum (Hatton, 2020, para 9).

Drama in schools incorporates both drama as an aesthetic discipline and as a

pedagogy for exploring and creating. As a pedagogy it is often valued in schools for its ability to engage students with other curriculum areas (Wilhelm, 1998). Drama invites participants to explore complex responses through fiction and employ both their affective and cognitive faculties to engage, resist and act (O’Connor et al., 2016).

As a pedagogy, drama welcomes play and experimentation for possibility thinking and problem solving, aligning it with the current educational focus upon creativity, resilience and flexibility (DICE Consortium, 2010). Educators acknowledge that drama elicits the playful, critical, the collaborative and the opportunity-seeking behaviours essential to the unpredictable future of our twenty-first-century learners (Pascoe, 2015). Drama can activate soft skills and engage diverse learners through integrated learning experiences in an imagined setting (Anderson & Dunn, 2013; Jablon, 2017). As Luton (2016) acknowledges, when drama entered the Aotearoa New Zealand curriculum in 1999 as a distinct subject, a number of schools were unprepared. Years later, drama classes continue to struggle for space, resources and expertise. Despite these hurdles, as an active and embodied medium, drama remains inclusive and accessible to a range of learners (Stinson & O’Connor, 2012).

In Aotearoa New Zealand, drama practice is underpinned by a strong ethic of manaakitanga (the shared values of integrity, trust, sincerity, equity) and ako (to teach and to learn). These two Māori concepts facilitate the shared negotiation of a kawa (etiquette or protocol) and provide a living agreement for praxis (Cody, 2015; Te Kete Ipurangi, 2011). Ensemble building within drama classrooms relies upon the creation of whanaungatanga or sense of family connection. Such a connection is supported by the dialogic relationship of teacher and student, which upholds ako through the provision of a space in which students are valued and validated (Cody, 2015). Enhanced by the physical, drama spaces work towards the ongoing development of learning communities that are democratic, and inclusive in which participants are heard and repositioned learners (Leggett & Ford, 2013).

As noted earlier, the majority of Aotearoa New Zealand drama teachers are particularly adept at flexible pedagogy and the challenges of adapting spaces. As detailed by Luton (2021), drama teachers have a greater reliance upon open spaces than others’ and accordingly make space for groups, rearrange furniture, or get rid of it. When teaching the default position of many drama teachers is alongside students in a circle to ensure interactions between both teachers and students (Kariippanon et al., 2017) This provides an embodied commitment to a collaborative pedagogy and the creation of an inclusive, democratic space (Vettraino & Linds, 2018). The drama classroom and its capacity to be open, transient and responsive lends ‘itself to transformation by participants and the teacher’ (Nicholls & Philip, 2012, p. 584).

Absent from the drama teacher’s classroom are the obvious distinctions between the teacher space and student space. As Lambert, Wright, Currie, and Pascoe (2015) explain the drama classroom is one dedicated to students’ becoming and offers a flexible space that can adapt to ‘varied pedagogical approaches and purposes’ (Nicholls & Philip, 2012, p. 586). It operates as a brave space for learning and creating that welcomes the ‘strengths and weaknesses of participants’ (Nicholls & Philip, 2012, p. 584) and is negotiated in partnership (Rands & Gansemer-Topf, 2017).

While there are parallels in the pedagogical strategies of the drama teacher and those advocating for ILE’s, little research currently exists on ILE classrooms and teaching in the arts. Designed to cultivate flexible, adaptable and mobile citizens for the competitive global economy (McPherson & Saltmarsh, 2016) the utilitarian goals of the ILE classroom remain problematic for the arts practices.

Does this resonate with you?

The contextualising for New Zealand is also interesting as Australian educators, take more notice of First Nations ways of thinking and knowing and being.

References

Coleman, C., & Thomson, A. (2021). No Drama: Making Do and Modern Learning in the Performing Arts. In N. Wright & E. Khoo (Eds.), Pedagogy and Partnerships in Innovative Learning Environments. Singapore: Springer Nature.

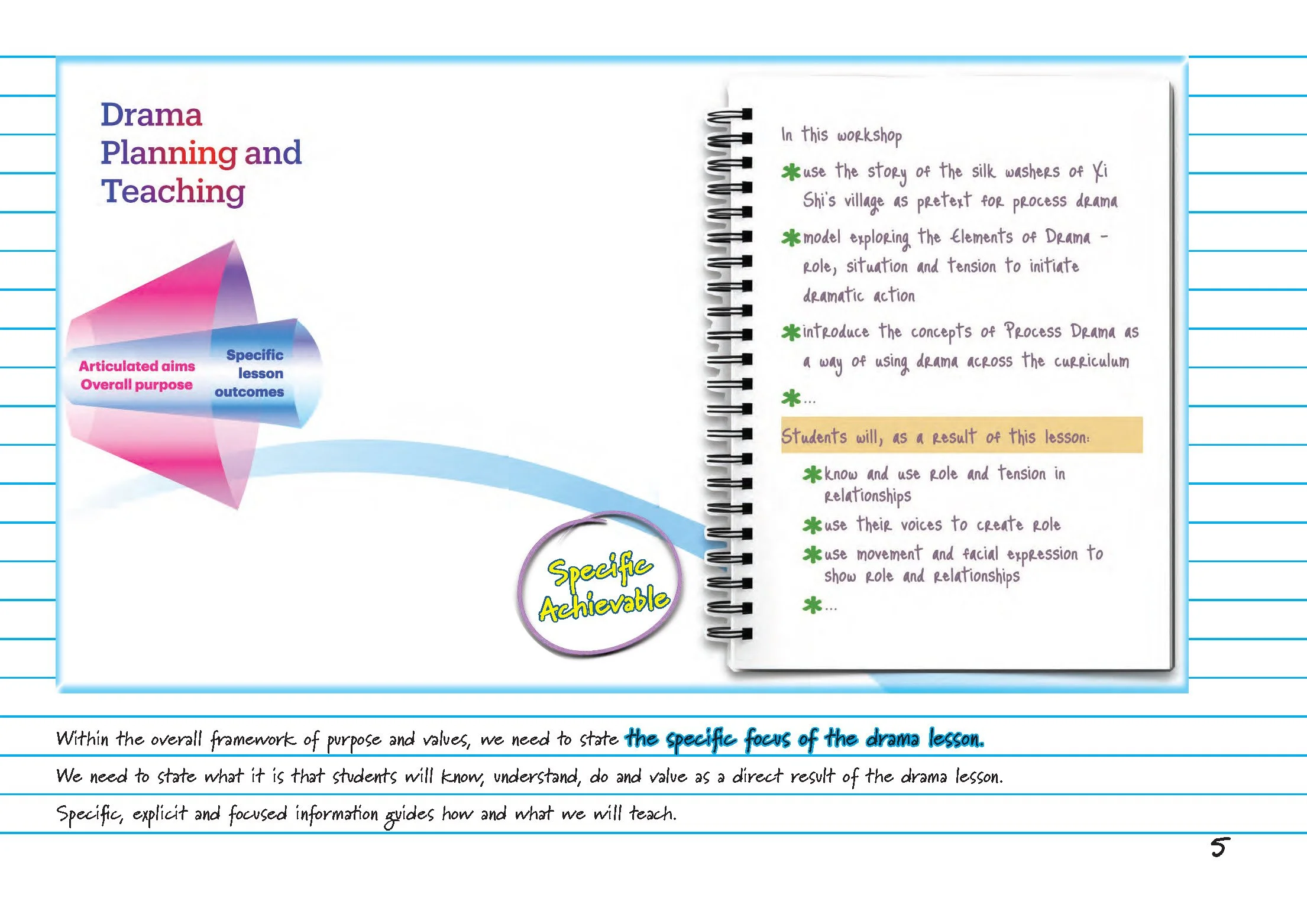

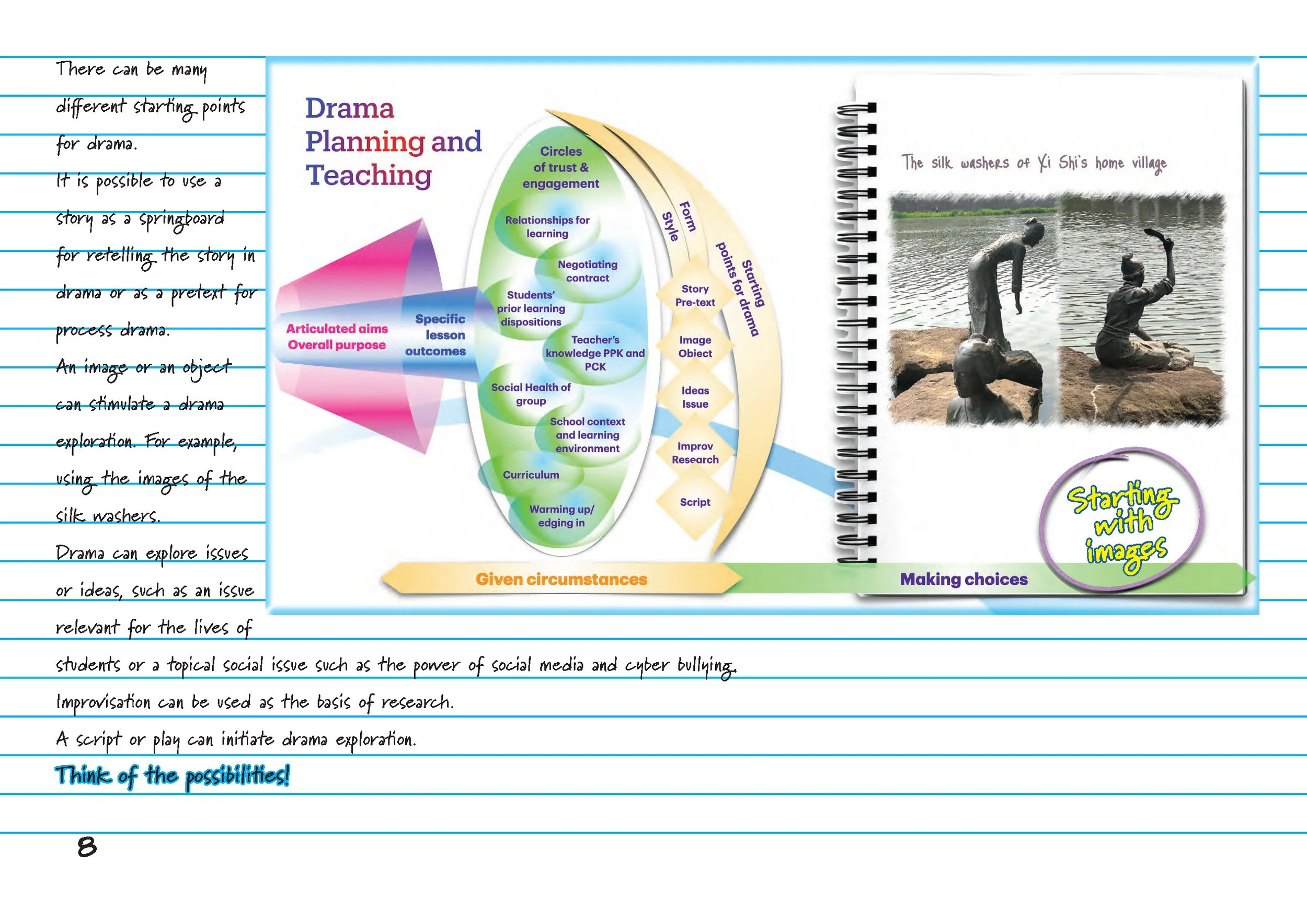

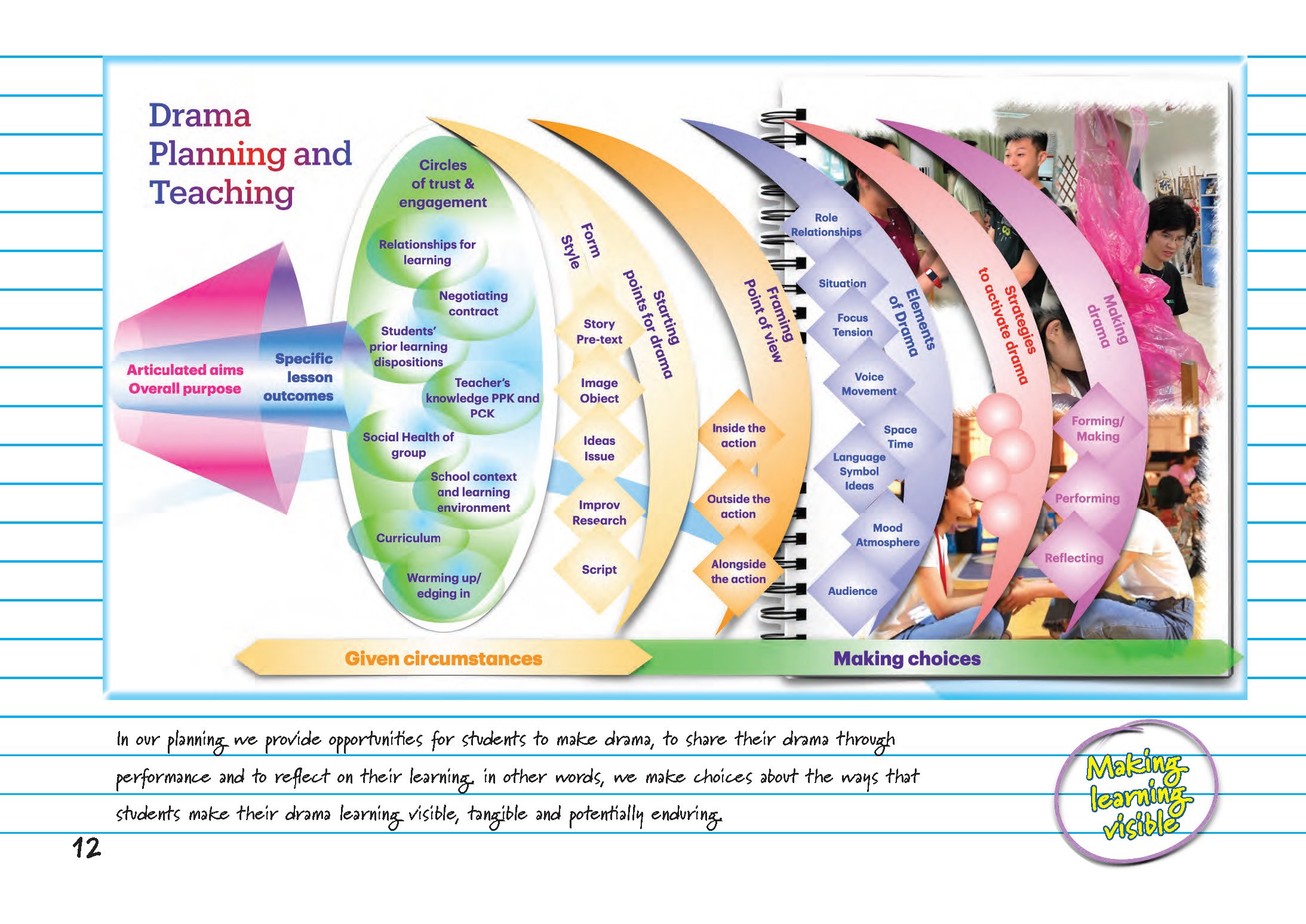

Drama Tuesday - Understanding what we do in drama lessons

/with a little help from emerging cognitive science.

Often as drama teachers we work from an intuitively felt and understood knowledge about what we do and why it works.

I have cherry-picked some ideas from a just published article by Rhonda Blair (2024) about the underlying processes of thought and action in the drama classroom.

Stanislavsky’s work in his final phase in the 1930s, his“last words”,if you will, is known as Active Analysis

Active Analysis…requires actors to “discover the underlying structures of actions and counteractions in a play before memorising dialogue. Analysis is ‘active’ because cast members examine the play ‘on their feet’ through improvisations that test their understanding of how characters on the page relate to each other and confront each other in performance. The technique encourages deep communication between partners and spontaneity; it also fosters simultaneous activation of mind, body, and heart, which Stanislavsky sees as necessary in performance” (Carnicke 2009, 212). The actors read the play, get up and improvise scenes, return to the text to see what has been missed, then improvise again and again until the improvisation captures it, at which point the text is memorised.

Stanislavsky’s work intuitively foreshadows what we now know about the emerging field of cognitive science.

Cognitive sciences support what theatre practitioners intuitively know: we are holistic beings, inextricable from our environments, which include each other.

In line with Active Analysis, we must stop imagining the body, feeling, thought, and action as being separate "containers" of aspects of ourselves: “Bodies are better conceived as processes, practices, and networks of relations…”

The argument in Blair’s article goes beyond this simple analysis and I commend the whole article to you.

Amongst the complex ideas about cognition and human experience, the work on “4E” cognition caught my attention for its resonance to my own practice.

Bodies and action are central in all of this, just as they are in Stanislavsky’s thinking.

This means creating an "authentic" character, following Stanislavsky, is an exploration, a process.

Bodies are shaped and affected by their encounters with each other. The key to who we are "is not in our heads or in our genes, but out there in the world" (8); we are "precarious autonomous systems" that make the world by coupling with our environment and each other (17).

This is what is going on with Active Analysis - engaging the text with others, entering the space, exploring, reengaging, and examining what’s happened in order to move ahead together. The actors read the play “today” and then get it on its feet “tomorrow”. As Stanislavsky writes, “What can we rehearse? A great deal. A character comes in, greets everybody, sits down, tells of events that have just taken place, expresses a series of thoughts. Everyone can act this guided by their own life experience. So, let them act. And so, we break the whole play, episode by episode, into physical actions. When this is done exactly, correctly, so that it feels true and it inspires our belief in what is happening on stage, then we can say that the line of the life of the human body has been created” (SS IX 1999:655, in Carnicke 2009, 194).

This then gives us clues about how we should/could think about the process we call rehearsing. More importantly, there are direct implications for the sort of drama teaching that is valuable.

Drama teaching should be embodied, embedded, extended and enacted.

What do you think?

Drama Tuesday - Teacher Education: Once more unto the breach…

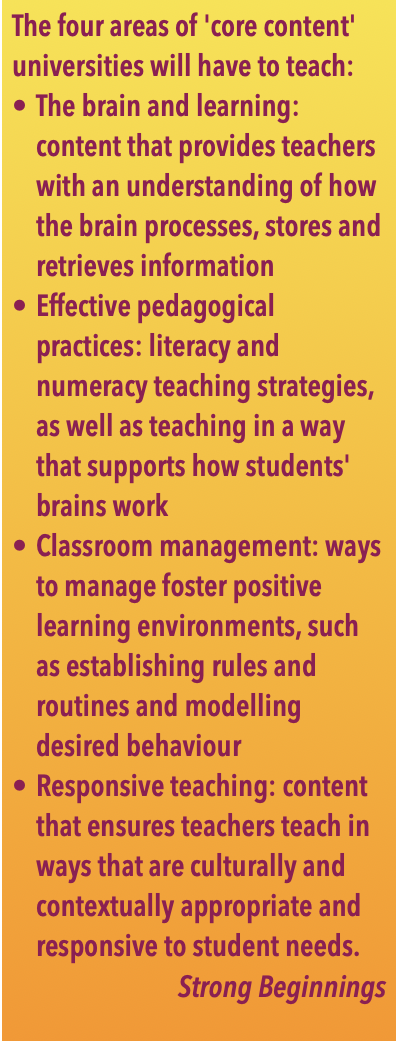

/Everyone, it seems, has opinions about what’s wrong with teacher education. I have lost track of the number of reports. The latest, Strong Beginnings, is by the Teacher Education Expert Panel chaired by Professor Mark Scott (2023).

The Report provides a series of detailed recommendations and draws on research of current ITE (Initial Teacher Education) students.

What are the gaps identified?

Harris and Grace in the Sydney Morning Herald sum up: “many beginning teachers were under prepared to teach in several key areas, including reading, cultural responsiveness, classroom management and family/carer engagement.” (2023).

Bita (July 06, 2023) draws from the report:

“One in three final-year teaching undergraduates surveyed for the Scott Report complained that their degree had been “too theoretical and focused on teaching philosophies’’.

Some 60 per cent of trainee primary school teachers said they had not been given many opportunities to practise the explicit teaching of phonics in classrooms – essential for children to learn to read and write.

Only half said their degree had given them opportunities to evaluate students’ progress, adjust instruction and provide targeted feedback.

One graduate called for “less information on learning philosophers and more information on practical activities/lessons to teach curriculum areas”.

“More hands-on experience would have been more beneficial than constantly writing essays,’’ another trainee teacher said.

“I would have liked more instruction on behaviour management and how to build my skill set when dealing with children with defiant or destructive behaviours,” they added.

There are echoes of the populist litany of deficiencies and eduspeak catchphrases: phonics, explicit teaching, classroom management. The use of terms such as “old school” and “back to the basics” reflects a limiting way of thinking about teacher education. But graduates are painting a grim picture and the remedies are being spelt out..

Young teachers will learn the old-school skill of explicit instruction” by clearly explaining to children what they are expected to learn, chunked into small and manageable tasks.

Teachers will be taught to plan a sequence of lessons that include repetition and practice, so that children can retrieve their past learning and consolidate it into long-term memory.

Universities must ensure that teachers can provide worked examples for lessons, and wait until children are proficient before expecting them to solve problems on their own. “Practices should include the use of structured lessons, clear and explicit instruction, effective questioning that encourages participation, reducing cognitive load and use of specific and positive feedback that acknowledges student effort,’’ the new standards state.

To be able to keep classes under control, teachers must be taught to “effectively model desired behaviour, such as respectful interactions, being organised, and being on time, to prompt positive behaviour by setting and reinforcing expectations”. (BITA, July 06, 2023)

I can imagine cohorts of university people clenching their buttocks and sharpening their defences as they tap at their computers.

With a touch of defensiveness I take a moment to question the perceptions presented by students and reinforced by those warriors of the culture and education wars.

When I look at my teacher education practice, how did my courses include explicit instruction, lesson and sequence planning, worked examples, assessment and classroom management?

Explicit instruction. My drama teacher education workshops begin from a premise: we learn drama by making drama and we learn to teach drama by participating in drama teaching activities. In other words, we learn by participating, we learn from the modelling provided, we learn from explicit instruction in and modelling about teaching drama. When we were learning about, say, improvisation, students were given explicit models of offer/respond/progress/build and then we modelled using this routine. When we learnt about Laban Effort Actions as a language of movement, we worked through ways of activating student learning in the and through them. That learning was tied to realising role, character and relationships and the other Elements of Drama. And I can add more examples of explicit instruction.

Lesson and sequence planning. Students in my workshops were provided with models and examples of lesson plans and sequences linked to both the Australian Curriculum (ACARA, 2014) and Western Australian syllabuses (SCSAWA). They were tasked with writing plans, sharing them with others and critiquing their own planning. When on school practicum, they were required to plan lessons and sequences of lessons.

Worked examples. When we worked with Process Drama, students were provided with worked examples that they experienced. They wrote their own Process Drama plans.

Assessment. In the Western Australian Year 12 syllabus, school students complete practical and written exams. To prepare students to teach the practical exam, my students also completed the requirements of the practical exam including writing and performing original solo performances, improvisation, scripted monologue performance and interview. My students completed portfolios of drama strategies, reflection and analysis. They wrote case stories. In other words, their assessment was tied to their future teaching of drama in schools.

Classroom management. Across all the workshops, practically, hands on and experientially, I model approaches to drama classroom management. Lessons are planned and shared explicitly. we modelled warm-up up, cooling down, edging into drama. We used methods of checking in, building relationships, providing feedback. We worked through protocols of setting high expectations, supporting diversity, being organised and positive learning environments. Our learning was tied explicitly to the AITSL Standards (2011)

It’s not possible to argue from one example that all teacher education addresses the issues outlined in the Scott report. Nor can we assume that all students understood the learning design in my curriculum (at the time). But you can perhaps gather that I sometimes rankle at ill informed criticisms of all drama teacher education.

Don’t get me wrong.It’s not that I don’t have criticisms of what was possible in my drama teacher education courses.

The need for more content. I was often frustrated by the lack of knowledge about drama that students brought with them to teaching drama. A desire to teach drama needs to be underpinned by active and expanding knowledge and ongoing professional learning.

The need for more time. To address gaps in knowledge needs time. Teacher education is time poor (and the constraints of universities and budgets kept cutting that time detrimentally).

The need for practicum experience with experienced teachers who know the curriculum and share a commitment to future practice.

But having acknowledged that the structural issues of Australian universities get in the way of the best possible drama teacher education, I do want to push back on the tabloid and politicised criticisms of teacher education. Of course, it can always be better. But sometimes the carping criticisms can be answered (if only people would listen!).

Bibliography

ACARA. (2014). The Australian Curriculum: The Arts. Retrieved from http://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/the-arts/introduction

AITSL. (2011). National system for the accreditation of pre‑service teacher education programs. Retrieved from http://www.aitsl.edu.au/verve/_resources/AITSL_Preservice_Consultation_Paper.pdf

BITA, N. (July 06, 2023). Old-school skills for new teachers as education ministers take control. The Australian.

Harris, C., & Grace, R. (2023, July 6, 2023 — 10.00pm). Universities who fail would-be teachers to be stripped of accreditation. Sydney Morning Herald.

Pascoe, R. (2022). Drama Teacher Education – A Long View Perspective. In M. McAvoy & P. O'Connor (Eds.), The Routledge companion to drama in education (pp. 471-483). Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Teacher Education Expert Panel (Mark Scott). (2023). Strong Beginnings: Report of the Teacher Education Expert Panel. Retrieved from Canberra: https://www.education.gov.au/quality-initial-teacher-education-review/resources/strong-beginnings-report-teacher-education-expert-panel

Drama Tuesday - Issues for Drama Teachers – consent, coercion, texts and the secondary school drama classroom

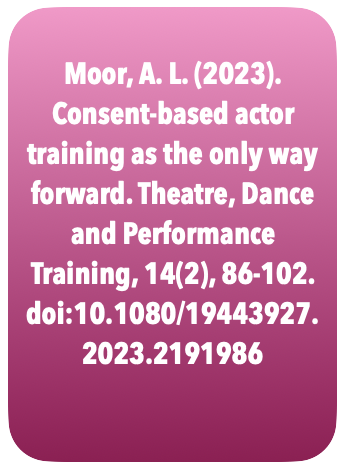

/ There is an increased attention to safe theatre practices resulting from the #BlackLivesMatter and the #MeToo movements. Reading the article by Moor (2023) alerted me to the impact on tertiary level Drama Schools and actor training leading to significant change. It then occurred to me to wonder about the implications for the secondary (or primary) school drama teacher.

What alerts do we need to have as drama teachers about ensuring our practice in the classroom and workshop is safe and appropriate? Drama classes include but are more than actor training. But how should we be considering the principles of consent-based actor training in the broader context of drama teaching.

Consent based actor training incorporates safe consensual agreement of touch, appropriate support in dealing with challenging material, non-biased casting, appropriate recognition of gender, safe acting practices, safe cultural practices, diversity of representation in teaching and directing staff and clear guidelines for discussion and complaint. In a nutshell consent-based actor training ensures the safety and agency of all actors in training (Moor 2023, p. 89).

These ideas prompt me to think more deeply about responding to these imperatives of drama teaching.

Consent.

As drama teachers we pay attention to creating engaging learning environments. We include warming up and edging into the drama activities to prefigure the lesson focus. We include cooling down and reflection activities to provide a frame for the learning focus. We include “rules’ about respecting ideas and opinions of others. In the wider framing of the learning, we need to also consider other ways of framing the boundaries of interpersonal behaviour. The Australian government has mandated consent instruction in all schools from 2023 (Leunen 2022). Awareness of consent, the setting or physical, social and emotional boundaries need to become part of our active protocols. This issue is more than sexual consent and focuses on principles of student agency and awareness.

What are the appropriate drama based activities for developing consent awareness in our drama students?

Coercion.

There is increasing attention to approaches to actor training (at all levels) where there are imbalances of power. There’s firm calling out of those acting teachers who claim that they “break then rebuild” their students. Nowhere is this responsibility of care more necessary than when working with younger students. How aware are we as drama teachers of the forms of subtle coercion we exert? How much pressure do students feel to “please the teacher” by doing what we suggest and direct.

I have often wondered when some drama teachers talk about “my vision” for the production, whether this is subtle coercive power at work (I could ask the same of any theatre director.) In a similar way, I wonder about practical drama exams where the expectation is that the students own original work is being shared – or supposed to be shared. Is this truly the student’s work or are they projecting the work of the teacher as director?

What awareness do we need to develop about the forms of coercion that can be found in the drama classroom.

Texts.

In the current education climate (especially in USA schools – see our earlier posts on banned texts) there is much attention given to teaching appropriate and acceptable texts. This is having a flattening effect on choices made by drama teachers. There is a need to consider carefully the content of all play materials and supporting texts. Much of the literary and theatrical cannon is open to question. Do well-known texts need more thought. For example, just a few from Shakespeare: Othello and The Merchant of Venice deal with issues of racial discrimination. Is Hamlet a play about mental illness? Romeo and Juliet deal with the consequences of impulsive teenage infatuation and sexual impetus.

The flip side of this is the reliance on “safe” drama texts that provide sanitised versions of life experience. That is deadening the impact and relevance of drama teaching and learning.

Do we need activation and trigger warnings? Has it come to the point where there is no safe text for drama?

The issues of inclusion, diversity, gender, bias, culture also could be added to this discussion.

Teaching drama is complex. Living in contemporary society is complicated.

And there is always a danger of losing sight of the goal of drama education by being weighed down by the other considerations (what sometimes teachers call “paperwork and bureaucracy”). But we can no longer plead ignorance as a defence.

Bibliography

Leunen, S. (2022). Mandatory Consent Education is a Huge Win for Australia but Consent is Just One Small Part of Navigating Relationships, The Conversation. February 21.

Moor, A. L. (2023). "Consent-based actor training as the only way forward." Theatre, Dance and Performance Training 14(2): 86-102.

Drama Tuesday - The Victoria Theatre Newcastle

/More than a Ghost Light Glowing in Memory

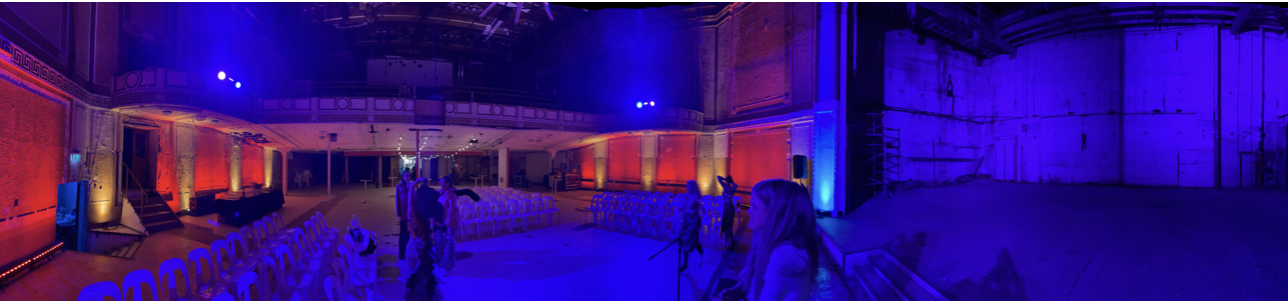

We are ushered into the theatre space after a long day of conferencing. It is the first time since 2018 that Drama Australia has met in person so we are happy to be with each other, catching up and sharing stories of what we have been doing.

The Victoria Theatre sits alongside the Crown and Anchor, a traditional beery smelling Australian pub, just off the famous Hunter Street (Bob Hudson sang of Hunter Street and the immortal refrain, Never let a Chance Go By, Oh Lord, to the top of the Australian charts around 1975; look it up on YouTube).

For the conference, we have been invited in to look and play before the building enters even more refurbishment.

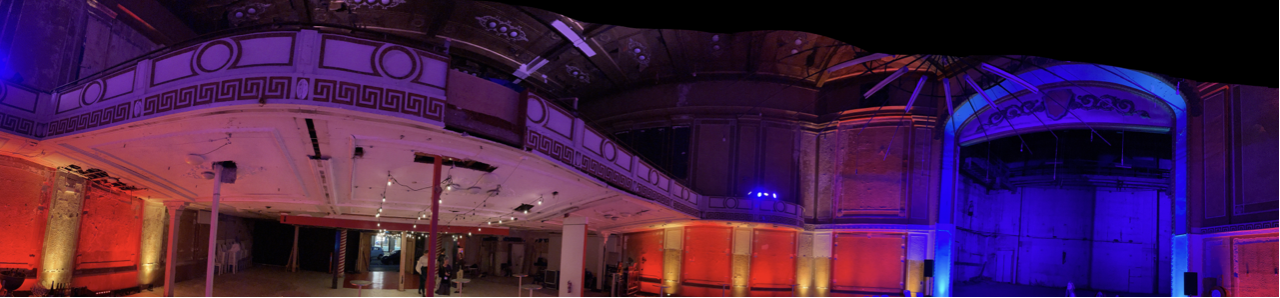

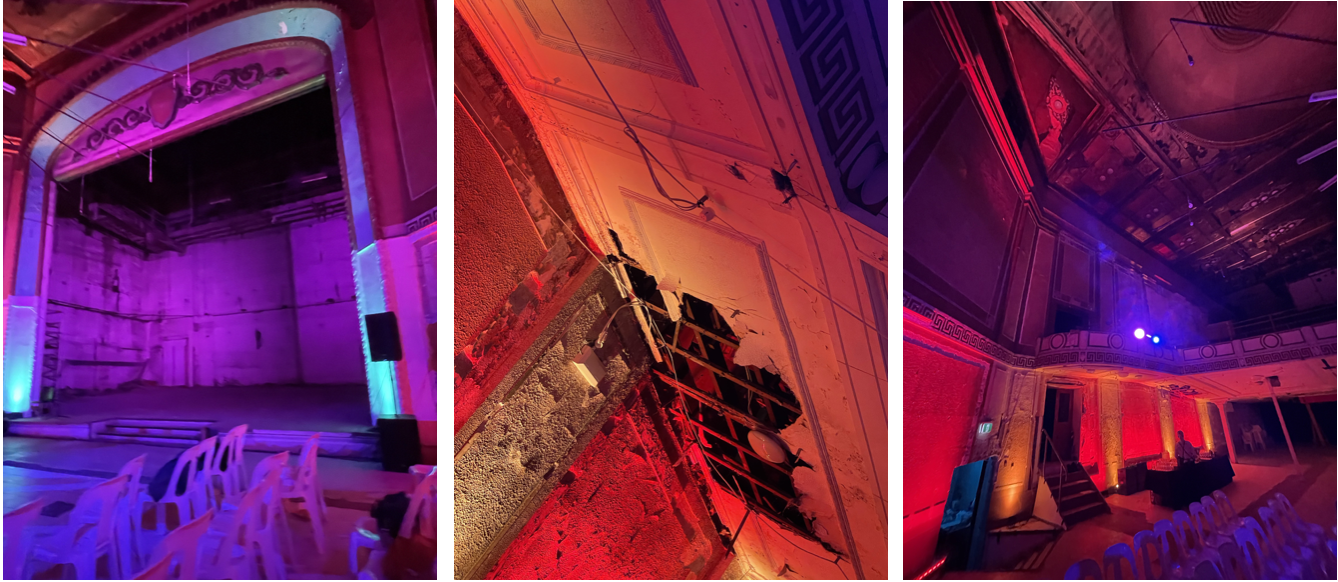

Stepping inside, the worse-for-wear space was lit with red and gold lighting in a sea of blue. Plastic chairs are arranged in the ‘safe space’ of the uneven floor. A table for drinks sits to one side. Above us a weird relic of perhaps a rock band era fades into the rococo plaster panels on the ceiling.

The once raked auditorium was long ago levelled so the floor sits a small step to the stage. But the stage rakes up with what looks like to be one in three and above the stage is a cavernous, darkened fly tower, the wooden scaffolding in shadowy darkness and eerie whistling wind.

I am entranced.

Atmospheric/ Beautiful in grungy splendour. Broken. Beautiful in tatters. Rough pockmarked scar tissue surfaces. Grime, ground into surfaces. Soft mouldy smell of age and decay. Panoramas of forgotten dreams.

History. Around 1857 the first Victoria Theatre with basic timber and iron construction was built on Watt Street behind the Commercial Hotel by Mr J. Croft (Mayor of Newcastle and licensee of the Commercial Hotel). But in 859: Croft's Victoria Theatre was destroyed by fire.

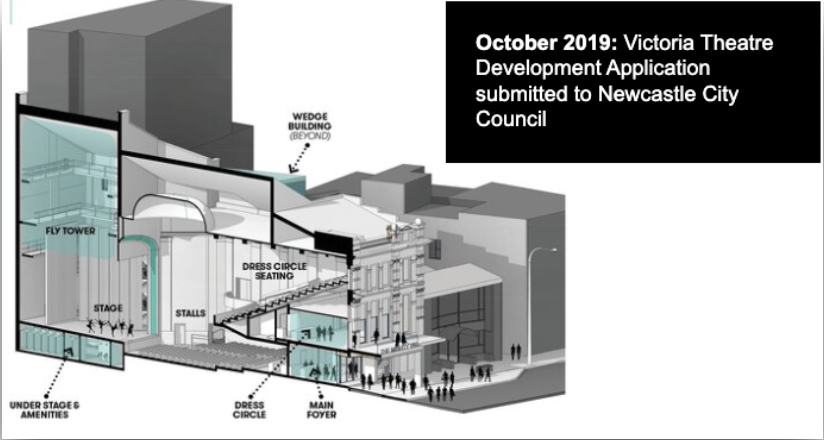

In 1876: a new Victoria Theatre owned by Mr John Bennett of Sydney opened on 8-10 Perkins Street and was Newcastle’s first purpose built theatre. It was built in 9 weeks with a timber structure and seated up to 1200 people. IN 1890 two new buildings were built 'over' existing building and then the existing building was razed. There was a hotel on the Perkins Street frontage with theatre auditorium in rear. Designed by architect James Henderson the Victoria Theatre as a four storey brick and iron building with fly tower and a Corinthian style facade seating 2000.

1906: Victoria Theatre reopens again after remodelling. 1921, reopens to accommodate cinema and in 1929 saw the arrival of talkies. 1930-60: Film dominates program although there were significant live performances throughout this period. 1966, closes as a movie theatre and place of entertainment; becomes a clothing store.

2015 local action saves the derelict theatre and attracts funding for refurbishment.

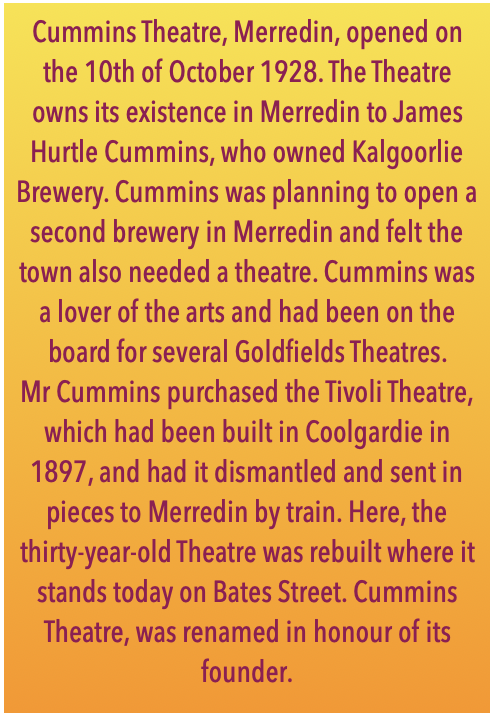

Theatres of the soul. We all have somewhere in our drama teacher souls, memories of theatre spaces. My first teaching appointment was to Merredin in the Wheatbelt of Western Australia. Arriving there in 1975 (to echoes of The Newcastle Song), I eagerly joined the Merredin Rep Club who had taken possession of Cummins Theatre.

It had been a cinema but still had a full fly tower and stage. Over 4 years 1975-79 (and one baby), we staged school productions and the annual dinner show with the Rep Club. When Liz and I married we moved into the Brewery House, or part of it. It had been built by Miss Cummins, the owner of the Brewery (long gone). I have fond memories of building sets and working in the rickety tin lined backstage and even climbing into the fly tower (something I wouldn’t be doing today!). I cut many a theatre tooth in that space.

The Victoria resonated with my own experience.

In those days, the Rep Club hosted (and manned security on) visits by passing rock bands – ACDC and bourbon fuelled raging Bon Scott. Production from the Playhouse in Perth followed by a drama workshop run by Aarne Neeme. The legendary touring production of Godspell when teachers from the High School refused to get off the bus as the company left town.

A little of my soul was left in that dusty theatre in Merredin. I found traces of it in The Victoria.

The opening Keynote by Associate Professor Gillian Arrighi (UNSW) challenged drama educators to think about why drama curricula give precedence to Western European legitimised theatre over the popular entertainments of music hall, magicians, singers, tap dancers and animal shows. This theatre was a wonderful answer to that provocation.

Send in the Clowns! And tap dancers. And Slapstick Comics. Blue jokes stinking of Mo (Roy Rene)/ The smell of the orchestra. The roar of the crowd.

A short report for IDEA from Ankara University where I am for the 31st Çağdaş Drama Derneği Congress.

/During the congress I made some notes to share with the IDEA Community.

The Congress theme was ‘change and transition responding especially after the Covid 19 pandemic when most things have changed in human life and in the drama field.

International workshop leaders

Joining the local participants were workshop leaders familiar to the IDEA Community. Patrice Baldwin, Juliane Lenssen from Berlin, David Allen, Dr. Christina Zoniou, University of the Peloponnese, Nikos Govas also from Greece.

Once again, we are reminded of the richness of shared knowledge within the field of drama education.

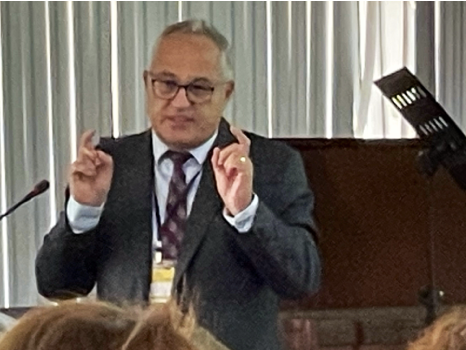

The congress included workshops and presentations from Turkish drama educators as well as keynotes. Of course, I had only a small window into those presentations, but share a couple of points that I think are of international interest.

Congress theme image: chameleon

A crisply articulate keynote from Prof.Dr. ÖMER ADIGÜZEL focusing on the Congress image of the chameleon. With a firm sense of humour Ömer noted that chameleon signal their social states responding to changing environments.

“Every action of a chameleon symbolises change, development and transformation - the Congress themes.”

He then noted the discrepancies between guidelines for schools and the realities of what happens. He highlighted the categorisation of drama and acting as “entertainment services” that gives the impression that the field of drama is limited to that category. And he concluded with discussion of the situation for training teachers to teach drama.

Chameleons also tell us about camouflage. I wondered about the times when we as drama educators needed to work our magic under the cover of camouflage.

Thoughtful and challenging ideas to explore.

A familiar controversy that IDEA needs to again address

Following a lecture from a German professor a member of the audience opened up a demarcation dispute: Drama pedagogy/Theatre pedagogy/Acting pedagogy (an issue that lingers in the very name of IDEA as an association – in English)

Are we seeing a world of education rent apart by unhelpful distinctions and marking out of territories. In the very title of IDEA as an association there’s a potential fault line that we dance on uncomfortably.

These terminologies niceties catapult us back to the so-called civil wars in drama/theatre education in the UK in the 1980/90s. They were not helpful then. Scar tissue still evident amongst some. I wonder if there are similar disputes in, say, music education.

Now may be another time to start a project that sets out to focus on describing key term and concepts. Such a project must not be about homogenising the field. Rather it is about acknowledging differences. There are differing conceptions philosophies and practices within the field we share.

Of course the aims and focus of training actors are vocationally specific. We are generally speaking not training young people in school or community workshops to be professional actors. Yet we must acknowledge that underpinning both is a fundamentally shared knowledge and learning about how we express and communicate ideas and stories for others. There are age and developmental differences but seeing past them, there is a fundamental need to use bodies and voices as resources for taking on roles that tell stories in embodied ways.

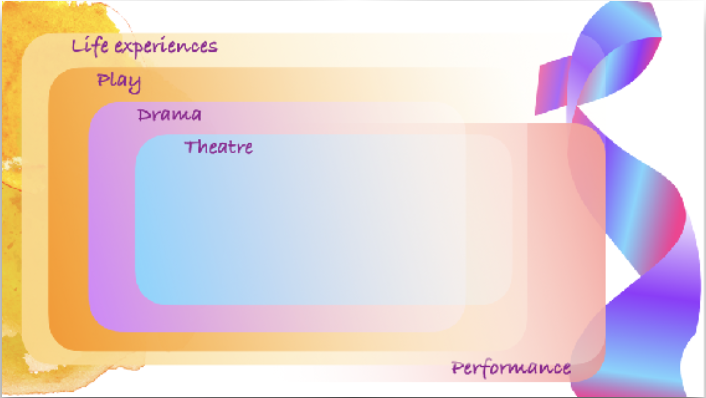

There is a fundamental relationship between related and interwoven fields of play, drama and theatre (drawing from he work of Richard Courtney (1988) which guided my approach to curriculum writing).

I have long relied on an image that helps me understand these relationships. Our field of drama education exists within the broad field of experience as learning. In life we have experiences of play that are further shaped into the broad field of drama in which we shape and shapers meaning through taking on roles. Within that wide field there are specific ways of making drama called theatre. They overlap with other forms of performance.

Lifetime Achievement Awards

At the opening of the 31st Congress of Çağdaş Drama Derneği I was honoured and humbled to be awarded a Lifetime Achievement Award.

I share a few words that I made in accepting the Award.

Shakespeare’s Hamlet told us that the “purpose of playing” is “to hold as 'twere the mirror up to nature”. That is an idea I hold closely in my life as drama educator. It has drive my career in education and in drama .

In accepting this award I thank you warmly and sincerely.

In turn hold up this award as a mirror to you and your work.

I have great admiration for your work as an association. Truly impressive. Inspiring. World leading. And I also warmly remind us that in our work as drama educators we are involved in the process of transforming lives as the Congress theme so strongly echoes.

I accept this award acknowledging my deepest respect for your work in transforming lives.

At the same ceremony Patrice Baldwin (also a former President of IDEA) was awarded a Lifetime Achievement Achievement Award.

Congratulations Patrice. Richly deserved recognition.

In my role as Immediate Past President of IDEA, I also passed on the message of congratulations from Sanja Krismanivic Tasic, current IDEA President (who couldn’t join the congress because of other commitments).

Workshop for Congress CABINET of DREAMS

For the Congress I developed a new 6 hour process drama that set out to tell a Brechtian Fabel to illuminate our understanding of teaching drama.

The participants in the workshop are invited to join a company of travelling players.

First we built the company – the Capocomico of the acting troupe and his family and their life on the road. Then they perform in a village that has never had a visiting troupe before. The nature of belief in performing is explored. The people of the village reject them but one of the villagers runs away to join them.

In the third part we explored how you learn to become a performer through an exploration of commedia roles. In the final part we hear of another troupe called the Cabinet of Dreams based on work that Liz Pascoe and I created with the Western Australian Youth theatre Company. That play asked questions about what is real and what is illusion in our work.

Interspersed with the drama making are moments reflecting on the approach I have used to planning this workshop. We talk about the Elements of Drama and the Strategies used to activate them. I presented this workshop twice: Thursday 26 and Saturday 28 October. Each group bring their dynamic and each time we will work from the same structure but make different drama.

I will make available to participants my planning on my web site www.stagepage.com.au where I also regularly/occasionally post about teaching drama.

The participants were enthusiastic, focused, knowledgable and exciting to work with. We had a great time (and again I thank and acknowledge my translator/co-teacher who enables me to do this work).

A reminder to us all as teachers

The impact of any teachers work is long term.

One of the participants in my process drama workshop here in Ankara, sidled up in the lunch break with the translator in tow to tell me that he was in my workshop in Mugla in 2015. He proudly told me that he had used some of the ideas in his practice with children and old aged people.

As a fly in/fly out visitor you never have opportunity or time to follow up on the workshops you do. So it gives a little heart flutter of satisfaction to have this feedback.

Thank you for taking the time to talk with me about your work

Opportunities to sightsee

There were opportunities for some sightseeing in Ankara. and on the return journey I was able to spend four nights in Istanbul. Although i have now been to Turkey for CDA four times, this is the first time I have been able to spend some time outside the congress walls. A fascinating into the local particularly because I was in Istanbul on the day that the 100th anniversary of the founding f modern Turkey was celebrated. An overwhelming sea of flag waving and colour and people on the streets celebrating.

I also made the pilgrimage that many Australians make to Gallipoli.

Robin Pascoe

4 November 2023.

Bibliography

Courtney, R. (1988). To Currick (Verb Intransitive) (1986). In D. Booth & A. Martin-Smith (Eds.), Re-Cognizing Ricjard Courtney Selected Writings on Drama and Education (pp. 86-90). Markham, Ontario: Pembroke Publishers Limited.

Drama Tuesday - Closely observed detail

/Creating role is paying attention to the details.

Feet on a plane - See observations below.

When we step into role we draw on our powers of observation of human behaviour. We use our bodies to symbolically represent someone else. We overlay our physical self with details of others drawn from lives observed.

I was struck by this idea when waiting in a call to jury duty recently ( Jury duty is another whole topic to explore. Remember the television drama that became a film Twelve Angry Men and female versions.)

Every Monday about 500 West Australian citizens of a certain age are called to be balloted onto the weeks juries for the District Court. With nervousness we sat waiting to be called. As I was sitting there (trying to read my novel but unable to do so) I was fascinated by the ways different people placed their feet. It occurred to me that the detail of feet told stories about those people.

Some had their feet firmly placed on the ground, knees spread open, exuding a kind of open confidence.

Others had feet and knees tightly bound together.

Yet another one had one foot twisted and resting on the other.

Someone has one foot placed ahead of the other implying they are about to spring forward.

There’s the foot tappers. Twitchers. Shufflers.

A long time ago I read an author’s notebook that was full of observed details with the advice to keep a similar notebook. And that habit of looking stuck with me. Maxine Green talks of wideawakeness to the senses.

There’s an important point for us in drama. We draw on these closely observed details to represent the roles we create. The term is psychophysical acting. By that we mean using a physical form ~ gesture, posture, facial expression or vocal inflection ~ to re-present to others the imagined or interpreted psychological state of the role.

That’s a big set of words for a simple process that is sometimes intuitively felt and realised. At the heart is the choices we make to move beyond the default language of our everyday bodies to show the role we become.

Theory has meaning when we clothe it in an immediate example. In this observational vein I am sitting in Dubai Airport waiting for QF8123 to Istanbul (heading to a conference run by Cagdas Drama Derniki, the Turkish drama education association.) Crowded. A middle aged wife has an argument with her husband about duty free when he asks her to hand over his passport and boarding pass.

An impassive African woman swathed in blankets, huddled against cold.

Despite the heat in the waiting area she is shivering cold.

Beside her an Asian woman slumps in fitful sleep.

On QF8123 to Istanbul, there was more to observe.

QF8123 has a completely different vibe.

Passengers with a sense of swagger trading in entitlement.

Three hooded young women are shuffled to upgrades seats.

In the vacant space a forward young man in a black tracksuit gathers three or four flight blankets and makes a nest his bare feet swung up into the arrest wriggling and intruding into the aisle.

There is a young couple beside me. He has a long flowing scrappy beard and he wears traditional long over shirt and loose fitting trousers. He pulls skinny legs up and bare feet scrunch up on the seat beside me. There is a strong smell of male urine. His wife is heavily closed. Together they share a vegan meal. When the other meals arrive he takes his wife’s meal, cherry picks, and tucks into the biscuits and non vegan cheese.

There’s a tour group from Hong Kong with an officiously efficient team leader with an autocratic iPad.

A young African woman with heavily braided henna red hair sits so the ropes of hair cascade in the space between seats and over the vegan meal.

The statuesque woman sitting in front of me struggles to collapse the handle of her roll on case. It won’t fit in the overhead locker (which Emirates quaintly call the hat rack). So she starts taking other people’s luggage out and moves it. No polite asking. Entitled.

Look. The world is waiting for the stories you tell.

Drama Tuesday - Making mistakes and taking risks

/Challenging perfectionism

We live in a world that sometimes sets us up for failure.

We see on social media Instagram Perfect Classrooms. We are told to strive for the best. Sometimes my university students are reluctant to submit their assignments because they are afraid that they are not “perfect”, not yet “as good as it is possible to be” (or read the subtext, I won’t get an HD!).

With some of these ideas in mind, I am presenting a paper workshop at the Singapore Drama Educators Conference in a few days. I am challenging the urge to be the perfect drama teacher.

The title: Mistakes, I’ve made a few. Reflection, Reflexivity and Drama Teaching

The proposal.This presentation/ workshop invites you to share stories of your memorable drama teaching moments as the basis of focusing on the role of reflection in drama teacher education.

Through the shared stories, we will explore the learning involved through processes of structured personal reflection. We will explore using Critical Incident Methodologies (Tripp, 1993/2012), case stories (Norris, McCammon, & Miller, 2000) as reflective tools for drama teacher education. The necessity of articulating Theoretical Frameworks for effective reflection and reflexive practice will be key outcomes.

This will provide an opportunity to consider approaches to drama teacher education: apprenticeships, mentored partnerships, university-based courses, and alternatives provided on-line or by associations.

The workshop is an invitation to share in a Community of Practice.

There’s a line in an old song that goes “mistakes I’ve made a few”. The line continues, “but then again, too few to mention!”

In my drama, teaching, I’m afraid the added line isn’t quite true.

One of the things that I could honestly say to my drama education students was that when it comes to drama teaching, I am able to speak from experience from the mistakes I’ve made. I don’t say that to beat myself up, but I do say it to indicate that it is important in drama teacher education to learn from our mistakes.

I heard about this idea of T-I-R Teacher in Role. I thought it would be easy. Without warning or preparation I launched into the role of a drill sergeant (modelled on my own school experiences of army cadets.

My poor year 10 students, ever compliant and ever hopeful, did their best. But the experience I offered was so far removed from their imagined and real worlds that the lesson limped along to a sagging conclusion. The activity had no specific purpose or connection to the lives of these students in a different time, place and school culture. What on earth was I thinking!

That of course is not the end of the story. Like every good teacher, I spent time thinking, reflecting, and doing something differently.

Peter Duffy (2015), initiated one of the books that he edited with the provocation to experienced drama educators: what was I thinking? This brought forth a succession of shared stories of drama teaching. Each of them have an insight into the thought processes, what Morgan and Sexton (1989) usefully called DramaThink.

In this workshop, you are invited to share your ‘’drama mistakes.‘’. Not in a mea culpa way but to stimulate reflection and reflexivity.

What are your “mistakes” in drama teaching?

Risk taking

In life we often advise people to avoid risk where risk is seen as something dangerous and potentially harmful. It’s risky to play with fire or to climb too high in the tree.

In drama we talk about physical risk and psychological risk. We do what we can to prevent students pushing each other around the drama room while they are on top of the lighting scaffold. We advise students to avoid negatively criticising other student performances or disclosing personal and private information.

Yet, it is important to also recognise that sometimes in drama teaching we have take risks in the sense of stepping into something that is new of different, trying something where the outcome is uncertain.

In this sense Risk Taking is a component of the decision-making process in situations that involve uncertainty and in which the probability of rewards and/or negative consequences are unknown. (Front. Psychol., 08 March 202. Sec. Personality and Social Psychology. Volume 12 - 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.562381)

In this sense, mistakes then are less failures and more risk taking with potential for learning fore future practice.

When are you a risk taker in drama teaching?

How do we slay the fiery dragon of perfectionism?

We are all human and that is what we must celebrate.

I am publishing the slides from this presentation alongside this post. You can find them here.

Bibliography

Duffy, P., Ed. (2015). A Reflective Practitioner's Guide to (Mis)Adventures in Drama Education - or - What Was I Thinking?, Intellect.

Morgan, N. and J. Saxton (1989). Drama: A Mind of Many Wonders, Nelson Thornes.

Norris, J., L. A. McCammon and C. S. Miller (2000). Learning To Teach Drama: A Case Narrative Approach. Portsmouth, Heinemann Drama.

Tripp, D. (1993/2012). Critical Incidents in Teaching: Developing Professional Judgement. Abingdon, Oxon, Routledge.

Drama Tuesday - Teaching is learning twice (and so is writing a keynote!)

/This week the Universe sent me a curved ball. The IDEAC hosts of the conference I am presenting for in Zhuhai, China in May sent an email. They asked me to change the topic of the keynote from their originally suggested one – on community and connection, the role of traditional stories in drama. Now, they thought it would be of interest to talk about the Australian Drama/Theatre Curriculum. Apart from my heart dropping at the thought of the sunk investment in a keynote written and the slides prepared, the new topic is interesting.

Given that I have spent almost my professional life knocking around in the curriculum writing and policy implementation field and that I have a passionate interest in drama curriculum and teaching it, I am happy to re-focus. But there is also the realisation that the challenge is not simply outlining the published words.

Curriculum is contested territory – everyone it seems has an opinion about what should be taught – and how it should be taught.

The Australian context needs to be sketched in. How do you explain 8 states/territories with primary responsibility for curriculum and teaching balanced against a national curriculum construct? Unlike some places where there is a top down national curriculum approach, the implementation is nuanced and can be variable (never forgetting that what happens in the classroom or school can also be mercurial and idiosyncratic.

Curriculum is coded. Curriculum is written in subject specific jargon (and must be necessarily so or is written in terms that don’t make meaning).

Curriculum is compressed information. When curriculum documents are written, they compress large amounts of information; they make assumptions about the knowledge and experience of the reader (and often overlook the need for specific terminology and concepts in an effort to be “readable”.

The “easiest” approach to this sort of task is to download and dump on the audience the words of the curriculum documents. But years of working with teacher education – preservice and those already teaching – tell me that we need to find ways of translating core curriculum concepts into user friendly language. Usually, this also means finding ways of visualising information to accompany the readers of the curriculum document. Beyond that there is the added challenge of transforming concepts into practical ideas. In other words, the task is to step beyond the curriculum on the page.

All of which is a preamble to thinking through the challenge: how do you explain Australian drama education to an audience who live in a different worldview, have different experiences and yet who are keenly interested in learning.

What would you write about the Australian Curriculum? (And which version?

Bibliography

Vaughan, N., Clampitt, K., & Park, N. (2016). To teach is to learn twice: The power of peer mentoring. eaching & Learning Inquiry, 4(2). doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.4.2.7