Drama Tuesday - Flowering in unlikely places

/There are many characters in my teaching career but one of them I remember with mixed feelings was the Deputy Principal of Western Australian Secondary Teachers College.

Somewhat typically of my generation we found his leadership was blustery and bureaucratic and not always warmly accepted. Intolerant lot we were, I know. But there is one story about him that continues to endear him to me.

If still from the deserts the prophets come (A.D. Hope Australia)

Early in his career - so the story goes - he was a teacher in what in Western Australia were called “one teacher schools”. That’s a school out in a rural community where all of the students are taught in one class. All ages from the youngest to the oldest (remembering of course that the age of leaving school was somewhat younger in those days). If you are familiar with the Anne of Green Gables stories, you may remember a similar school was featured.

As the single teacher of the school the person I’m talking about decided that he would mount a production of Shakespeare’s Hamlet. This involved all the students in the school. The littlest students, in homemade costumes stitched together from flour sacks by willing mums, were the guards on the battlements of Elsinore. The production was staged in the school room with rudimentary lighting and makeshift scenery put together in woodworking Friday afternoon classes the hammering alongside the line memorising. The roles were shared across all the students according to their capacities but everyone, including the teacher, had roles.

Maybe rough and ready. Maybe not the Bell Shakespeare. But, according to legend, it had energy and verve. And heart.

When you think about all the incidental applied learning and the bringing together of community involved, there’s a kind of rough magic to the teaching.

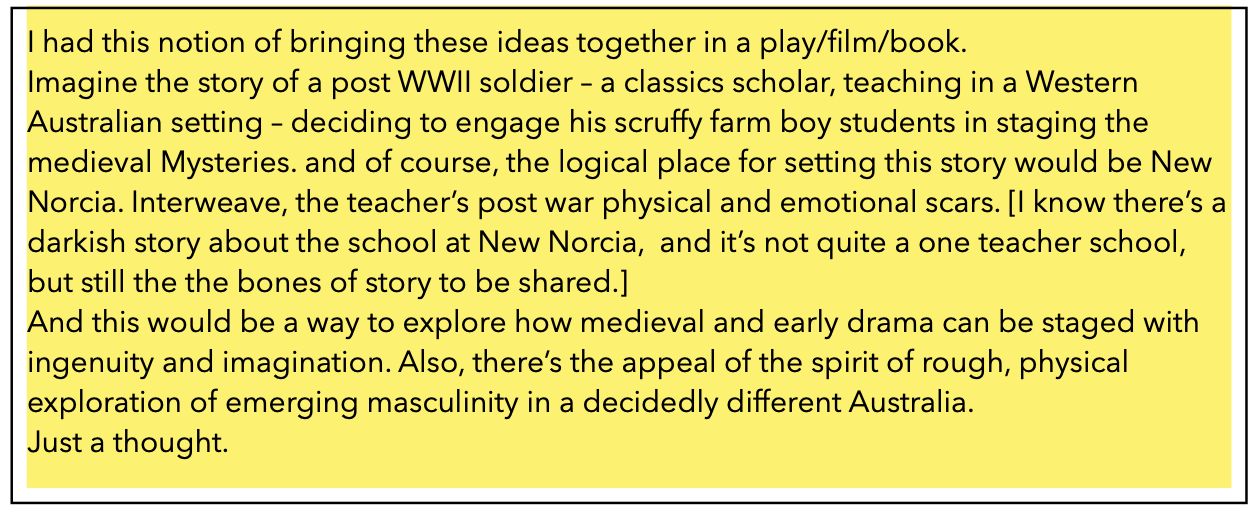

Edward’s Boys ensemble in the 2013 production of Shakespeare’s Henry V, directed by Perry Mills. Photo by Gavin Birkett, courtesy of Edward’s Boys.

Let’s not over romanticise this. It’s the sort of thing that happened in the straightened years after the Second World War when there was a flood of returned soldiers and airmen adjusting to the recovery years. This story seems incongruous with the image I have of clashing impatiently with him in his role as Deputy. But we should give credit where credit’s due.

On this unworthy scaffold to bring forth (Shakespeare, Henry V Prologue)

Cambridge University Press

978-1-108-81023-4 — Performing Early Modern Drama Beyond Shakespeare Harry R. McCarthy in the Elements in Shakespeare Performance series

This story came to mind today as I read about a contemporary drama production project in the King Edward VI Grammar School (KES), reputed to have been attended by Shakespeare. Over time within the school there’s developed a theatre project known as Edward’s Boys dedicated to ‘striving to explore the repertoire of the boys’ companies’ under the direction of the school’s deputy headmaster, Perry Mills. Edward’s Boys is an amateur troupe composed entirely of pupils (aged 11–18) from the school which has been in continuous operation since 2008. They have performed at the grammar school in Stratford on Avon, as well as on tour in venues as varied as Oxford college dining halls, the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, St Paul’s Cathedral, a chapel in Montpellier, and a ducal palace in Genoa. “These productions constitute the largest corpus of early modern boy theatre in performance available for examination by twenty-first-century scholars.”

The focus of this company is a range of early

modern dramatists such as Marston’s The

Dutch Courtesan and Antonio’s Revenge, extracts from Lyly’s Endymion and Mother Bombie, Middleton’s A Mad World, My Masters and A Chaste Maid in Cheapside, and, Dekker and Webster’s Westward Ho!. They also have produced Shakespeare’s Henry V

As McCarthy observes,

“these unique productions had been distinctly shaped by the company’s institutional context and their development of a vigorous, contemporary performance style … in the hands of Edward’s Boys, early modern drama becomes a site of sport and play, of physical experimentation, and of exploring contemporary boyhood.”

There is something quaintly and quintessentially English about the notion of exploring the early repertoire built on a company of “scholar actors” in the spirit of the companies of boy actors in Shakespeare’s times.

It’s also inspiring. And thought provoking.