Drama Tuesday - A Primer For Arts Education

/A quick Primer on teaching the Arts in schools

Sometimes it is useful to restate fundamental principles about teaching and learning the arts. You answer questions about:

1. Being clear about why you are teaching the arts

Teaching the Arts begins with a choice on your part: you choose to teach the arts so your students can know and understand the arts in their own lives and can use the arts to express their ideas and feelings and communicate them with others.

But your teaching always begins with a choice on your part.

While Curriculum Authorities can provide syllabuses and mandates, you need to ultimately see the purpose and value of your students following those curriculum mandates. You begin by answering a fundamental question: why am I including the arts in the priorities I make about what is important for my students to know, do, value and learn.

2. Being clear about what you are teaching your students to know, do and value in the arts

There are often misconceptions about what you teach in the arts.

Let’s start with the BIG IDEA.

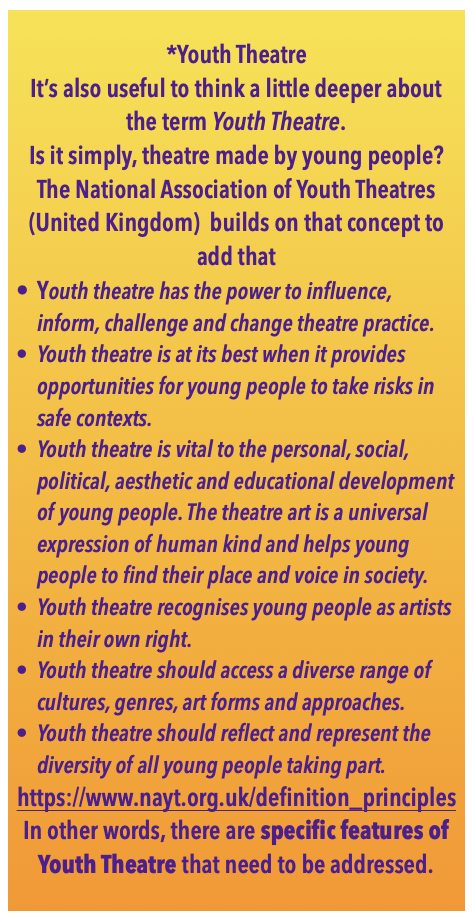

You are teaching students to be artists and audiences for the arts in their own lives, cultures and societies. You are teaching students how they find their personal, social and cultural identities through making and responding to the arts.

To achieve that BIG IDEA:

You provide opportunities for students to experience the arts. They use their senses to see and hear and feel arts experiences. They experience a wide variety of arts immediately, directly and relate them to their own lives.

In that context, you provide students opportunities to make their own arts - to express and communicate ideas, feelings, experiences directly through the mediums of the art forms.

What you teach in the arts is therefore something more than singing a song or improvising a dance or drama or making a colour wheel, or recording a video – it might involve those activities but not on their own or in isolation. What is being taught to students is how the arts provide ways of expressing and communicating and why that is an important life value. They are applying their learning about the arts from experiencing the arts, to making the arts. They are being taught to be artists and audiences.

Another way of thinking about what students are learning is that the chosen arts activity for a lesson, is a vehicle for the broader learning, rather than just an activity to complete. For example, how does the song being song in the lesson, add to or develop what students know about the elements of music and the role of music in people’s lives. This is, after all, the question we ask ourselves as teachers about any learning activity in any curriculum area: how does this chosen learning activity contribute to students’ learning? The activity must always be the vehicle for the learning.

3. Being clear about how students learn in the arts

Learning in the arts is experiential, hands-on and practical.

Students learn the arts by making the arts, by experiencing and responding to the arts, by applying their knowledge and skills – what they have learnt – to their own making and responding in the arts.

Learning the arts is experiential. It is through direct hands on experiences of the arts as audiences, and as makers and artists, that students learn.

That does not mean that there are not times when you are directly teaching students about the arts. It might be that you are demonstrating a specific skill or technique. It might be that you are sharing knowledge about the history and cultural, social and personal contexts of specific arts experiences tracing continuity and change over times, places and cultures. These are the times when you, as a knowledgeable other share your knowledge to provide “zones of proximal development” (Vygotsky) with your students.

Learning in the arts is also progressive.

It is developmental, recognising that students learning needs are different according to their ages and their physical, social, emotional development. In choosing arts activities they need to be age and developmentally appropriate for your students.

It is organised and structured. Students learn in the arts through a widening spiral of experiences that provide increasing challenge. A spiral curriculum model that is not haphazard or random. Students have a clear understanding of how what they are learning today builds on what they have already learn – and which also is leading to further future learning.

4. Being clear about your role in in your students’ learning in the arts

Your role in your students’ learning is clear.

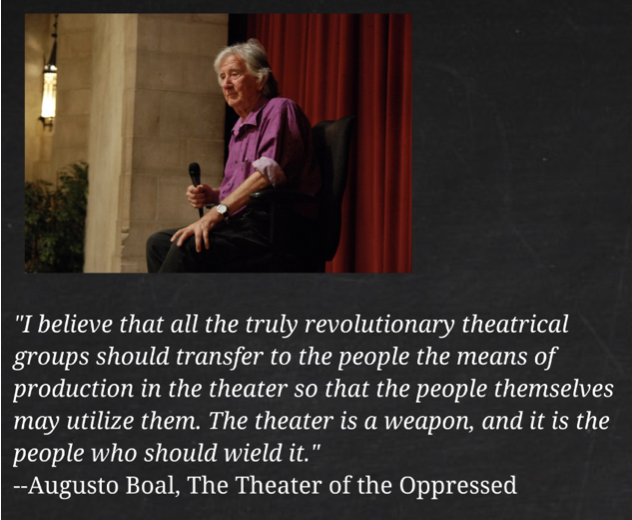

You guide. You inspire. You model. You share knowledge. You facilitate. These are overlapping not mutually exclusive roles.

You can sum up your role as the co-creator of learning. Your provide contexts, materials, knowledge as required, supportive and safe environments. You provide guidance. But, you are not the director of the show, the invisible hand wielding the brush, the composer of the music. You model your own creativity alongside your students as they create, but you given them voice and agency – while modelling your own.