The Ghost Theatre

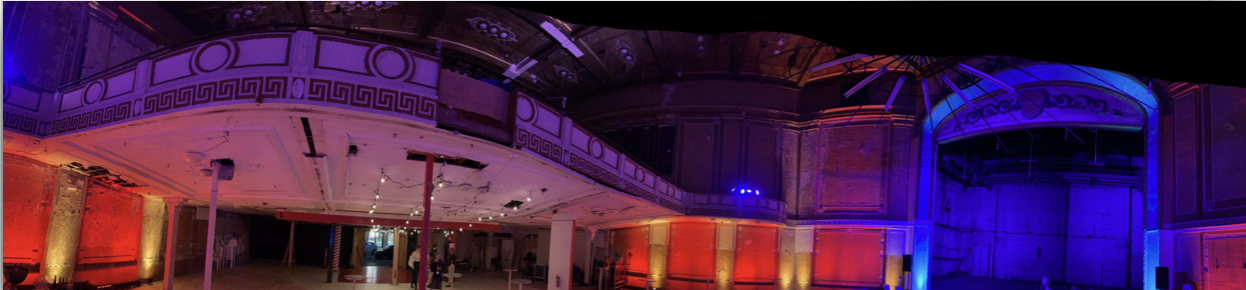

A girl from the marshes of London is thrown into the role of being prompt for the boys playing at Blackfriar’s Theatre. 1601. (pages 19-21)

‘If they skip a page or two don't worry; but let them know afterwards.' She gestured with her lantern. 'Keep your eye on Trussell, the boy who brought you here. He’s playing Julius and I have a bet with Lord Nonesuch that he won't get through a single act this year without making a mistake. Easy money.'

‘And what about Nonesuch?’

Her sniff was one of pleasure. 'Him? He is absolutely guaranteed to go off script, I think it's a point of principle with him. But that doesn't mean he needs prompting. Drying up is not that boy's problem.' Alouette settled herself. 'A prompter and curtain-up only a quarter-hour late. It must be my lucky day.' She locked her eyes on Shay's and said, ‘Sharp eyes, blunt knives.' Shay repeated it back, self-consciously.

Conversations were snuffed out with the candles and there was a weight to the darkness then, like the room had filled with oil. A wedge of scenery was wheeled onto stage before eyes got used to the dark.

There was a last, delicious moment of calm before Alouette lit the lamp in front of them.

There it was. The prow of a ship, cresting and burrowing into waves.

Aquamarine silk undulated across the floor. It was at once profoundly unrealistic and utterly beguiling. Alouette worked a bellows laid sideways with its spout angled towards the bow and she sent up a glimmering spray of water. Shay caught the smell of deep sea with no land in sight.

The ship curtseyed to meet the waves and when it rose again Nonesuch was on deck with his hands on his hips. He was Cleopatra. Bird-eyed and horse-maned. Black silk that captured ripples of sea-light and gold at his ankles and wrists. Gold that was too plain for jewellery, but too rich for shackles. He turned a degree so that the light split his face in two. His first line, according to Shay's script, was, The waves know my fate, and Caesar's too, but he continued to stare out in silence. There was a reverie to it: the creak of wood and the smell of salt, the candle light and hushed breaths. Shay tugged at Alouette's hem, Should I? but Alouette shook her head.

Our hearts are ships.

He didn’t say it the way she was used to hearing players talk. Rather he threw the line to the front row of the audience, quietly enough that they had to lean in a little closer.

Our hearts are ships; he said again, and when life’s weather is fair we tell ourselves that we are our hearts’ captains. It is us who steer the course. We set sail for new lands. We explore.

He flung his arms wide and turned so that he was almost entirely in darkness. There was the tiniest glint of light from his eyes. Aloute dimmed the lantern until he was little more than a voice and a glean of gold.

But that is an illusion. When true storms come, they pluck the ships of our heart up and toss them this way and that. We are no captains, Instead, we hang on for dear life, clinging to the mast as the winds rage around us.'

He blew out his cheeks against the squall of the spray. His hair was damp and flustered.

Our hearts are ships, he said, louder now as Alouette worked the bellows. And tonight the tempest is here. The storm is upon us and my heart is lost on a killing sea.'

Shay looked in vain at her script; not a word of the speech appeared there. Nonesuch stood taller, extended a hand, and blew. Tiny paper boats, as small as thistledown, streamed from his palm, and all over the theatre hands reached up into the light, and then, in one moment, Alouette killed the lanterns and a curtain fell.

Well, I suppose that was scene one, she said.

The play unfolded with a dreamlike imprecision, Nonesuch the centre of every scene. Cleopatra came to Rome to plead for her country, truffling for power. One minute he rolled, untouched, from a carpet to land propped on an elbow, the next he flattered Rome like a courtier. Caesar's part was taken by a brute of a boy, six foot tall and wide as a door, whose toga rode up while his laurel crown bulged at his temples. No matter, he was pure foil. Nonesuch worked in and out of his shadows with a voice half for himself and half for the audience. He fitted between the sexes, sometimes in the space of a sentence. His body lied and cajoled, flattered and fretted, and Shay found herself tangled up in him. When his words tumbled like rainwater, her heart rate rose with his. When he dropped to his knees, it was Shay's gut that clenched.

She missed her first prompt. In the middle of a long speech, Trussell simply stopped. Shay had been watching four gentlemen who sat in chairs set on the edge of the stage, close enough to the action to reach out and touch the actors. Indeed, in the middle of a knife fight one had pulled out his rapier and offered to help Trussell out, a suggestion which won a smattering of weary laughter from the main seats. Two of the gentlemen were engaged in a game of dice and Shay was distracted until Alouette elbowed her in the ribs.

By the time she'd found her place another actor had taken over the speech. She checked the script and found that the cast had missed out chunk. She cursed herself. Alouette's expression was unreadable in the dark but Shay was sure that she’d moved away from her. She had other chances though. In a long soliloquy a soldier stopped for a moment and bit his lip. She whispered his line to him and he went on without pause for the rest of the speech. The next scene was riddled with corrections in her text and three times actors lost their way. Each time she nudged them back.

Near the end of the act Nonesuch went out among the audience.

He trailed fingers over bare shoulders as he walked. He whispered something into a gentleman's ear that won a blush and he sat in laps.

He looked so fragile among the heft and luxury of the noblemen that, when the interval came, Shay found she'd been holding her breath; she was damp with sweat.

The black-clad boys of the chorus slipped onto the stage as the musicians started up over their heads. Fiddle, lute and hand drum stepped around one another until a loose volley of trumpet notes sounded out, tiptoeing across the bridge of sound. It was the Moor from backstage, standing among his sitting comrades, sending forth curling breakers of frothy, bubbling notes.

Shay asked, Is Nonesuch really high-born? I can't place him at all.' Alouette turned the lantern onto her. It was blindingly bright. She scowled and then relaxed. ‘That is what they say. He's certainly as lazy as a gentleman. And he does have a taste for the finer things. But I've never heard him talk about his past. She considered the question again. There are whispers that he was taken from a very wealthy family.' There was a Nonesuch Palace in Ewell. A Nonesuch Hall. It was a name made of stone and glass. 'Surely a family of means would have the power to get him back. The owner, this Evans, he can’t be untouchable?' Alouette worked as she talked. Evans has the Queen's ear, More importantly, he has the Ole ent Warrant. Who knows what happened?

Maybe his people fell out of favour, maybe this was a warning, Still, I’ve, never seen Nonesuch with kinfolk so iy could all be nonsense. Don’t ask him.

Shay nodded and then felt the heat of the lantern back to her. Seriously don’t ask. They have so little, these boys.

The Moor’s trumpet stepped down through the scale to land, breatheless on the hush, and Alouete dimmed her lantern. This here is his family now.'

When second act began with a long speech from Nonesuch There was a weight to his words that she’d not noticed earlier. His voice was a blade returning to a sheath, a pigeon coming home to roost. And his power was doubled, trebled even, by Alouette's lighting. Her lanterns were mirrored and directional, throwing beams of light that always caught Nonesuchs face. She could dim and brighten, flattening his features or throwing him into the shadows. She played with the light the way Nonesuch played with words and the two of them warped the very air to their bidding. At one point, with Cleopatra alone on a storm-tossed hillside, Alouette slid a sheet of cracked tin in front of the lantern, dropped a greyish lump of something behind it and, as the scene reached its crescendo, lit it. There was a blinding flash and a throat-tearing pall of smoke in the box, but on stage the effect was unmistakable: lightning, splitting the backdrop from ceiling to boards and fixing Cleopatra's agony in an eye-blink of white light. Alouette's face was taut until there was a chorus of gasps and then a round of applause so loud that Nonesuch had to halt his speech. Shay was so caught up in the action that it was only when she turned over a page and saw the next was blank that she realised the play was over.

Even if she'd been up on stage, Shay didn't think she could be more drained. She sat, winded, as Alouette tidied and the chatter of the crowd drained away behind them. She loaded up a clever wooden box with drawers that folded out like a fan containing wicks as thick as fingers and others as delicate as thread. A drawer lined in lead was packed with twists of paper that smelled of gunpowder. The tin stencils slid into a series of slots and she read out the names as she replaced them. Dawn, Storm, Dusk, Battle, Hell! Once the last stencil had gone back into the box Alouette turned to Shay. 'So? How was it?'

'I loved it. It was true. She was thick with the weight of the drama, drunk on it. I'm so sorry that I missed that first cue.' Alouette nodded. You have to let them hang at least once otherwise they wouldn't bother learning the lines at all.'