Features of Good Practice in Drama

Some of the following features will always be present in all successful drama lessons. Others may be more relevant to particular contexts. Together they go a long way towards ensuring purposeful and satisfying learning.

Drama is at the centre of the learning

Drama is the focus; all the activities that students undertake have a basis in drama. There are many other things being learned in successful drama courses . These are significant. However, the focus of this course is on a range of drama experiences, the practical exploration of taking on role and using the elements, traditions and conventions of drama.

Students understand the connections between the different aspects of drama

Students make sense of the course. They explicitly articulate and recognise that there is a connectedness between all the aspects of the course: for example, through a study of text and heritage students understand drama forms and styles which they can use in making their own drama or when responding to the drama of others.

Students use drama in expressive, creative and interpretive ways

Drama is not the application of formulae. It is an expressive, creative and interpretive art form rather than a mechanical process. Successful drama is characterised by sensitivity as well as attention to accuracy

Drama activities are matched to students’ development, age and abilities

Activities and resources used are appropriate to the students’ levels of development, to their interests and to their levels of experience. Experiences and interests of individual students are recognised and extended to benefit the development of the class as a whole

Students clearly understand what they are doing and why

The plan for the course is published and understood by students. Plans for sections of the course are explained and connections made explicit for students. They should also be given an understanding of how the current lesson or series of lessons fulfills the longer term plans.

In addition, students can articulate the immediate purpose of the work they are doing. They can use sets of strategies for tackling the tasks at hand: for example, in a group improvisation task they are familiar with and use strategies like brainstorming ideas, trying out ideas in practice, group direction of improvisations, structuring devices that may be used in improvisation, and so on.

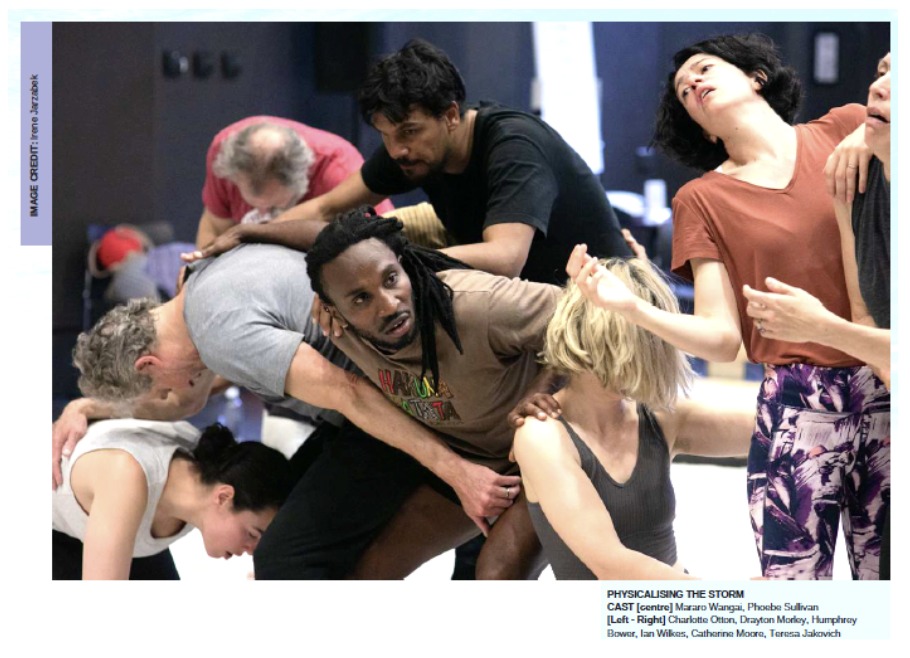

Activities are varied, are taken at an appropriate pace and are planned to involve a range of skills

The type of activity determines the amount of time, the pace and the sense of purpose given to it. Some activities - such as exploring and developing ideas in character scoring - need quieter and more reflective approaches than, say, exploring the dynamics of relationship in dialogue, which needs a more active approach.

Teachers need to be particularly aware of the tendency for some students to participate passively in drama. While recognising the need for quiet and reflective opportunities, drama is energetic and energising. It is not passive (even when still); students need to be encouraged to participate and their learning experiences need to be chosen to support engagement. In other words, students should not be allowed to “hang out”; in improvisation, for example, teachers should side coach when students don’t make offers.

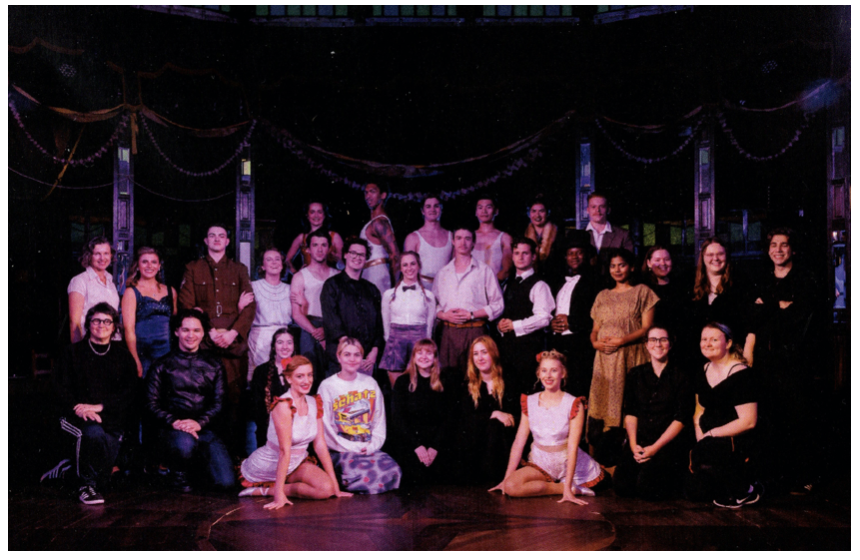

Students work in a variety of groupings

Drama is almost always collaborative. However, students need a variety of approaches to working. Not only do they need to understand the principles of working productively together, they also need to understand individual goalsetting and reflection.

Students use a variety of learning styles

Students have a range of learning styles. Effective teaching and learning programs in drama recognise a range of learning styles - including, rote learning, narrative learning, visual learning, verbal learning, analytical learning, multi sensory learning, symbolic learning, numeric learning - and use these styles according to the needs and development of the students in particular classes.

Teachers use a variety of teaching styles and interactions

Just as students have a range of learning styles, so teachers need to use a range of strategies. Drama lessons should not settle into an too-predictable pattern (which doesn’t preclude there being a sense of routine and purpose to drama lessons)

Resources are used selectively

There are many useful drama resources published and available. Some provide a theory base and others are “recipe books” of drama activities. Any drama resource used - a visiting performance, an in-theatre performance, a drama text, a textbook - needs careful consideration.

Teachers need to identify how the resource supports the planned program. They need to recognise how the resource complements their strengths as a teacher and how its use will add value to the learning of students. They match materials to the capabilities, ages, development, needs and interests of students in the particular class. They work with the resource beforehand, wherever possible, and relate it to the program.

Students need resources that challenge them; they need, for example, to work beyond the familiar, to have dramatic texts that broaden their experience especially when their life experience is relatively narrow.

Particular care needs to be taken when using resources that may be of a controversial nature. In choosing performances for students to see, in choosing dramatic texts for students to use, teachers need to be aware of the particular contexts in which they are working: for example, the religious or social background of students. There is also a need to recognise community standards. While drama has in its long history often challenged values and beliefs, it has also reinforced and confirmed them.

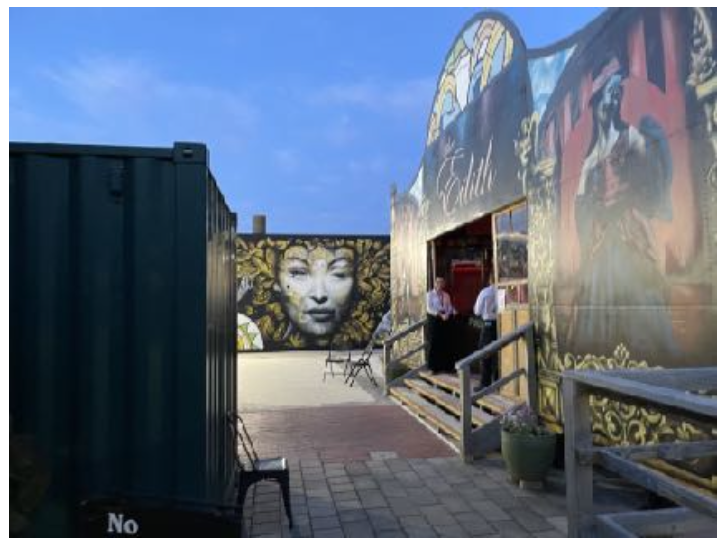

Equipment, resources and facilities are used productively

While, at one level, drama is bare boards and a passion, many schools have access to purpose built spaces and sophisticated drama equipment. These need to be exploited as fully as possible.

Some activities are planned in conjunction with other Arts forms and learning areas

Increasingly there is recognition in education of the connections between the arts forms of dance, drama, media, music, visual arts and multi-arts. While keeping drama at the centre of the teaching and learning program, there are opportunities to enhance learning through making connections between drama and the other arts forms.

Cross curricular themes are explored in drama as well as other learning areas.

Diversity in drama is recognised

Students develop a sense of their drama making in relation to wider community contexts beyond the confines of the classroom. Teachers need to actively assist students to understand the diversity of drama in Australia and other cultures. They can use their local communities as resources for drama learning.

Programs acknowledge the potential for development of both personal identity and Australian culture through drama

The broader implications of drama learning programs are recognised and supported.

Students experience a wide range of drama including professional drama.

It is sometimes easy for the drama of students to becoming self fulfilling prophesies; in other words, they work within a narrow range of known drama forms and expectations.

Students need not only to see and experience a range of drama performed by professionals and to professional standards, but also to connect their own drama making to the wider community of drama.

Assessment and evaluation are integral to teaching and learning

Students and teachers are involved in assessing the nature and quality of drama. Through discussion and exploration they come to a shared understanding of standards of drama. Teachers help students to extend their drama ideas and explore other choices and possibilities. Students actively participate on making their own judgments about the effectiveness of their drama rather than passively waiting for the teacher’s assessment.

The portfolio is particularly useful in that it provides a record of the development of the student and articulates the processes that underpin drama activities - many of which are performances that are not available to be recorded in the way that an essay or mathematics problem may be.

Where summative assessments are made, they are done so on the basis of clearly stated criteria and transparent processes; in other words, students clearly understand why and how a particular mark or grade is given.

Work done out of class supports the overall drama curriculum

Pupils have access to facilities, for instance during lunch breaks. This enables them to pursue their drama interests individually and in groups in relaxed circumstances. Appropriate safety measures must be taken.

Homework is planned and purposeful, providing consolidation and reinforcement; students, for example, may explore characterisation in detail and learn dialogue.

Where students have relevant experience from other learning, this is actively included in the program; for example, a student may have taken dance classes out of school or been in a television series. This experience can be drawn on in the drama program to enrich the learning of other students.

In particular, there is recognition that drama often involves rehearsing and other work outside the confines of the classroom - and outside the hours of school. Not only is this recognised by students, there is also due credit given for this work.

Teachers are reflective about their practice and the learning of their students

Effective teachers use metacognitive processes to articulate the learning of students and to inform the ongoing planning processes.

Teachers are reflective about their practice and the learning of their students

Effective teachers use metacognitive processes to articulate the learning of students and to inform the ongoing planning processes

In Part 3 the focus is on Safe Practice.