Arts and drama educators mostly get on with their day to day teaching. This week ACARA, the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority launched The Australian Curriculum Version 9. On the whole, the focus of this major revision, politically driven, has been on strengthening Phonics in English and on headline grabbing issues amongst some such as “strengthening and making explicit teaching about the origins and Christian and Western heritage of Australia's democracy” (once again reinforcing the deep seated suspicion of dark motives in curriculum writers, sensed by some conservative Australians.

There are changes for the Australian Curriculum: The Arts – I will write about them in a later post.

For now I focus on the relative quiet amongst the media and public about the changes in Version 9. Where is the uproar. Where is even the ripple of recognition that a change has been made that has consequences to teaching and learning?

Put simply, there is nothing showing on the Richter Scales of Education.

The new version, despite the consultation that happened in 2021, is sinking like a stone unnoticed.

In fact, Arts Education is not on many people’s radar this election.

Not surprising given the focus on cost of living (petrol prices rising; inflation figures burgeoning) and the bickering and scrapping tone of the election and going for the jugular gotcha moments that dominate the media feeds.

But is anyone noticing that Arts Education is floundering in the quicksand of Australian education. Passionate few struggle to lift it up. But generally, as an education community, our focus is elsewhere. Not waving, but drowning.

I share the media release from the National Advocates for Arts Education NAAE in full.

Is anyone listening?

Certainly, this call falls on deaf ears of my rusted-on local representative.

ACARa advises. Version 9 will be implemented by states and territories according to their own timelines. ACARA will maintain the current Australian Curriculum website with Version 8.4 curriculum and both websites will remain live until such time as there is no need for schools to access Version 8.4 of the Australian Curriculum.NAAE statement about the 2022 federal election

Who we are

The National Advocates for Arts Education (NAAE) is a coalition of peak arts and arts education associations representing approximately 10,000 arts educators across Australia. NAAE members are Art Education Australia (AEA), Australian Dance Council – Ausdance, Australian Society for Music Education (ASME), Australian Teachers of Media (ATOM), Drama Australia and the National Association for the Visual Arts (NAVA).

NAAE advocates for every Australian student in primary and secondary schools to have access to quality Arts Education across the five arts subjects: Dance, Drama, Media Arts, Music and Visual Arts. We ask all political parties to endorse this principle.

Why arts education?

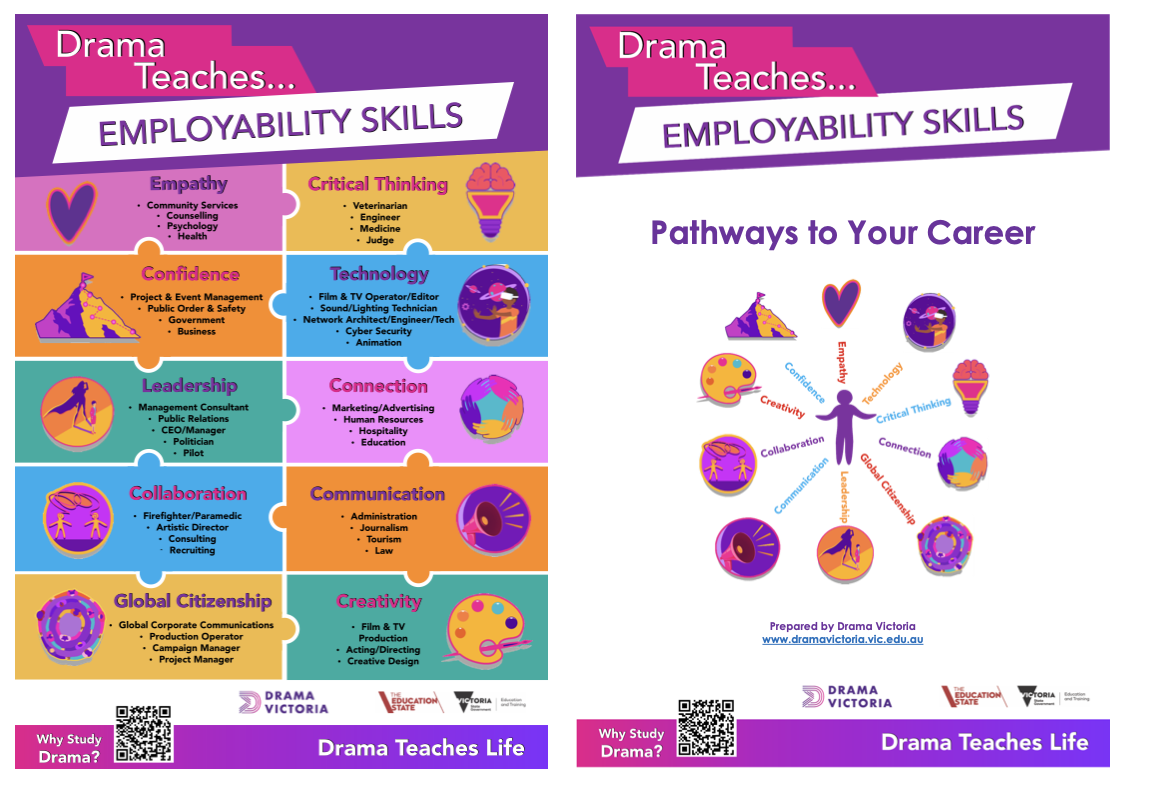

Australian and international research has continued to show the multitude of benefits that The Arts can have on student academic and non-academic outcomes. Arts Education not only fosters the development of artistic skills for art making, but it also teaches skills in collaboration, innovation, experimentation, resilience, confidence, problem-solving and communication. Research finds that students who engage in The Arts do better academically in their non-Arts subjects than those students who do not participate in The Arts (Martin et al., 2013).

There is ample global evidence (including Australia) that speaks to the explicit value and benefits of an Arts rich society. This enrichment begins and is contingent upon access to quality Arts Education. Arts Education plays an essential role in preparing young people and industry professionals to respond holistically, meaningfully, and purposefully to the impacts of global events. The long tail of COVID, coupled with catastrophic climate events and significant global conflict all point to the necessity of and need for Arts education in Australia.

It is now time to halt the erosion of support for arts and arts education that has occurred over the past decade. We ask for meaningful investment in quality Arts Education across all levels of Australian society. This means making a tangible commitment to providing increased support for rigorous and sophisticated opportunities for teaching, learning, making, producing, and creating into the future.

What we are calling for

The National Advocates for Arts Education are calling for all political parties to consider and endorse the following policy imperatives.

NAAE urges all political parties to commit to the development of a National Cultural Policy that includes Arts Education and is developed in consultation with artists, arts educators, the community, and peak arts bodies to ensure a well-supported arts and cultural sector that is serving the Australian community.

NAAE calls for support for implementation of arts curriculums across the five Arts subjects in each state and territory in Australia from Foundation to Year 12 with targeted professional development, training, and education programs.

Halt the erosion of arts specific education training in Initial Teacher Education (ITE) to increase curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment course allocation time for The Arts. This extends to specialisations and time for arts learning in early childhood and primary education courses to ensure teachers are well equipped to teach at least one Arts subject in depth. See NAAE’s submission to the Quality Initial Teacher Education Review here.

Undo the current government’s university fee increase to Creative Arts courses. We call for an equitable tertiary education system that does not target Creative Arts degrees with increased fees on the false basis that this area of study does not lead to employment. See our August 2020 statement and September 2020 statements for more details.

Increase funding to the Australia Council for The Arts to specifically include funding for teaching artists in schools for existing and future programs, as well as support for arts engagement programs with students and for teacher professional learning.

The National Music Teacher Mentoring Program (established by Richard Gill and implemented through the Australian Youth Orchestra) be expanded with additional funding to ensure early childhood and primary school teachers also have professional learning support across the other four Arts subjects: Dance, Drama, Media Arts, and Visual Arts.

NAAE calls for the removal of political interference in Australian Research Council (ARC) directions for Australian research. Earlier this year we raised concerns about the increased level of government interference in independent peer-review processes, and major implications for the type of research that will occur in years to come.

Given the concerns raised above, NAAE calls for a federally funded Review of The Arts in Australian Schools. Within the past 15 years, two federally funded reviews have been conducted into two arts subjects; National Review of School Music Education: Augmenting the diminished (Pascoe, Leong, MacCallum, Mackinlay, Marsh, Smith, Church, and Winterton (2005) and First We See: The National Review of Visual Education (Davis, 2008). These have been significant, important, and valuable reviews that were completed before the Australian Curriculum: The Arts was endorsed in 2013.

It is now timely to recommend another review that will include the five arts subjects (Dance, Drama, Media Arts, Music, and Visual Arts) included in the Australian Curriculum and how various national, state, and territory arts curriculum is being implemented and taught in Australian schools. NAAE has proposed a draft terms of reference for the review which include:

Relevant Australian and international research published in the last ten years, on national arts curricula in schools focusing on best practice delivery and resourcing models.

Map current curriculum provision (intended curriculum) and implementation of curriculum (enacted curriculum) across the five Arts subjects in each state and territory in Australia from Foundation to Year 12 to ascertain: which Arts subjects are implemented in primary and secondary schools; which teachers implement the five arts subjects; how schools manage the time required to provide quality Arts learning experiences for students; and, what is the ‘actual’ time provided for each Arts subject. An analysis of the differences between the intended curriculum and enacted curriculum is required to investigate the elements that nurture and hinder implementation.

Map current Initial Teacher Education (ITE) and Early Career Teacher support offerings nationally in education courses (across early childhood, primary education, and secondary education) and identify lecturer expertise, assessment types, number of units, and hours allocated to Arts education.

Examples of effective primary school programs that provide sequential foundational learning in the five arts subjects.

Provide recommendations for:

future iterations of arts curriculum and implementation at a national and state/territory level.

provision of Initial Teacher Education for The Arts (and any implications for AITSL to consider).

improving Initial Teacher Education programs in Arts curriculum and pedagogy, across early years, primary and secondary pre-service teachers. o

ongoing professional learning for primary generalist, primary specialist, and secondary specialist teachers. Recommendations for the Commonwealth, State and Territory Governments, Teacher Accreditation Boards and Universities to consider.

a range of best practice delivery models of The Arts in Australian schools.

NAAE acknowledges the extensive research and industry evidence pointing to how and why Australian society looks to Arts Education to foster individual and collective resilience in crises. We ask our policymakers to do the same.

Meaningful investment, proper resourcing, and support in the form of sustained professional learning and adequate initial teacher education for Arts teachers are essential for how we leverage the unique skills and understandings obtained by the field in recent years. This is going to be essential for how we work together to understand how change is experienced on the ground, and deliver on the ambitions of version 9.0 of the Australian Curriculum.

For further comment contact:

John Nicholas Saunders, Chair, NAAE at contact@naae.org.au