Drama Tuesday - Swimming in the infinity pool of drama education

/Reflecting on the status of drama education

Robin Pascoe, Honorary Fellow, Murdoch University, Perth, Western Australia

An infinity pool is a swimming pool in which water continuously flows over one or more of its edges. This produces a visual illusion of water without a boundary, appearing to be vanishing or extending to infinity.

Drama explorations are powerful ways of engaging students in possibilities, creative opportunities to enter worlds where they have options. In taking on role, we ask students to be simultaneously themselves and others. They can make choices to explore ideas and situations beyond their immediate lives. Students living in suburban Perth can, for example, become group of refugee children on a boat from Sri Lanka. Students can imagine themselves confronting plague in other times and pandemic in their own. Students can question, wonder and challenge. They can explore their own lives and situations as well as imagined ones.

Teaching and learning drama – like the infinity pool – does move towards unlimited possibilities. In taking on role and exploring situations through creating productive tension, we embody physically, mentally and emotionally the potentialities of human experiences that can be real and imagined. This is exhilarating and potentially life-changing opportunity for our students. But it’s also challenging. As drama teachers we carry a weight of responsibility. The choices we make as teachers about subjects explored and roles taken, need to be responsible. When our students move into dangerous places, we need to know how to lead and manage experiences safely. We and they can be caught so strongly in the rip tide of the moment that we lose sight of the impending danger of drifting towards the cliff or edge where we crash over the abyss.

In a recently completed chapter for the Routledge Companion to Drama Education (Edited by Mary McAvoy & Peter O'Connor, Routledge, 2021/2) I explore the concept of “abyssal thinking” and its impact on drama teacher education. Santos (2007) identifies abyssal thinking as “a system of visible and invisible distinctions, the invisible ones being the foundation of the visible ones. The invisible distinctions are established through radical lines that divide social reality into two realms, the realm of “this side of the line” and the realm of “the other side of the line”. In the case of the infinity pool, this side is inside the pool and safe; the other side is over the edge into the unknown.

What are the lines we draw as drama teachers? What are the limits of our practice, the edges of safety? When do we cross the line? Can we swim on both sides of the line?

How do drama teachers stand astride the line between safety and risk?

After a lifetime of teaching Drama in schools and in universities, I am often struck by the observation that there is still a lack of acceptance of the place and value of drama. I wonder about what leads to this resistance to recognise that the teaching and learning of drama is life-enhancing and valuable. What leads some to put drama the other side of the line?

Drama is risky business

Some drama education teachers can find themselves being drawn towards unsafe practice. Some focus, concentration and warm up activities, for example, while helping students step into the drama can also take them into darker places. Some warm ups are considered too trance-like. There are reports of drama lessons where students disclose events that too revealing. The subject matter explored is sometimes considered too confronting or questioning of authority.

In fact one of the major criticisms of drama in schools, driven by fear from some parents and community members, is that drama taking their children into places that they don’t want them to explore 1. They argue that drama classes are loose and uncontrolled “therapy sessions” where “it all hangs out”. They argue that the topics explored are “subversive” and question the status quo. The texts explored in drama are considered to be “unsuitable”, questioning values and social norms. As drama educators, we can be considered to be on the other side of that invisible line of what is acceptable (June 09, 2020). These sorts of myths about drama in schools are inflamed in the context of “culture wars” (Brownstein, February 15, 2022; Hunter, 1991) As much as we might scoff at this characterisation of drama education, we need to take these criticisms seriously or we risk being rendered invisible (see Finneran, 2008 for a critical lens on the mythologising of drama education).

We need to be clear about the limits of drama in schools. Drama therapy is, as I tell my drama teacher education students, a legitimate field of therapeutic healing with medical protocols and protections, but this drama education course is not a drama therapy course. Drama therapy addresses specific mental health issues. “Drama therapy is an aesthetic healing form that … [draws] its uniqueness among psychotherapies is that it stems from an expressive, aesthetic process--the art of drama and theatre” (Landy, 2007). It provides “a safe space for individuals in specific mental health and community settings to explore telling their stories, expressing their emotions, and finding new ways of looking at their situations, fostering a greater understanding of their experiences, as well as improved interpersonal relationships” (Snyder, 2019). As drama educators, we do provide safe spaces and encourage understanding of experiences but we also need to be conscious of the limits of our field and have strategies that help us know them – and when we need to seek help from trained health practitioners. When drama lessons unveil significant mental health issues or disclosures, we need to have skills to defuse situations and capacity to channel any student to the needed help.

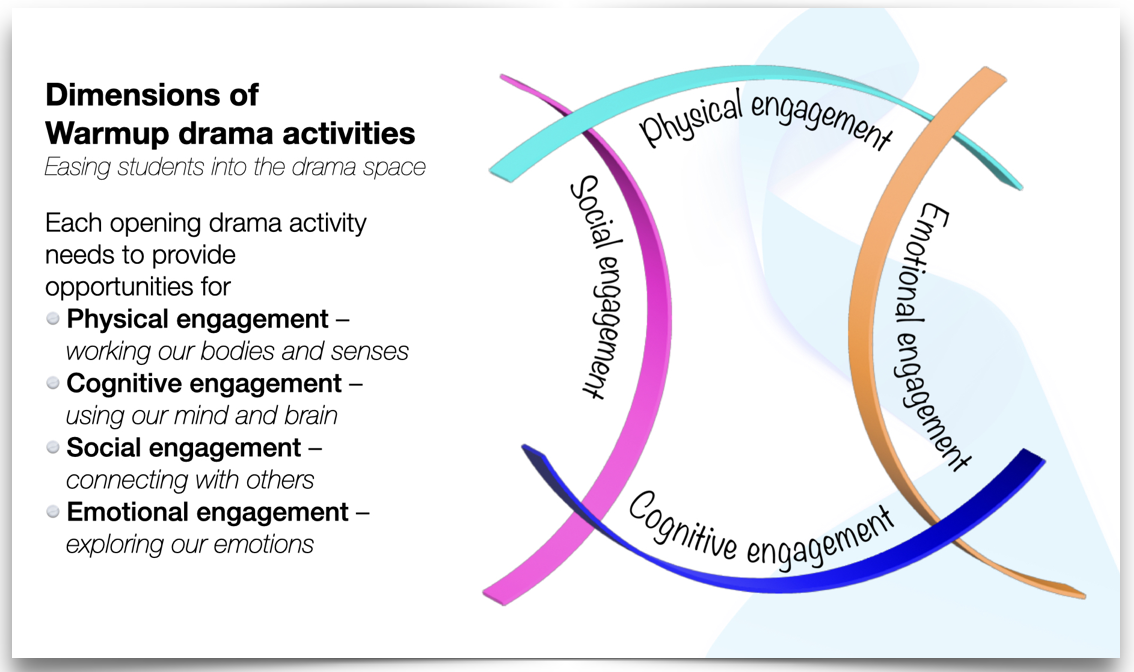

To help balance on that abyssal line, it is necessary to reaffirm the purpose and limits of what we do. For example, the purpose and focus of the activities that help us initiate drama – loosely, our warmups – need to recognise that they are something more than games and that they need to have clear educative purpose. They serve as a bridge from the world outside the drama space and the safe space for exploration. They necessarily should pre-figure content, skills and processes of the drama lesson. I have written before about the skilful choices drama teachers need to make about their warm ups. In easing students into the drama space, each opening drama activity needs to provide opportunities for:

Physical engagement – working our bodies and senses

Cognitive engagement – using our mind and brain

Social engagement – connecting with others

Emotional engagement – exploring our emotions.

These principles also apply to the content of our drama lessons. The choices that we make about the content of the drama exploration should be made with care. We need to understand how the topics we choose challenge and have relevance for students. We need to recognise that the drama we make can often set up dissonances between parents and students, between community and students. Drama education has long been associated with “progressive education practice” and identified with “subversive thinking” (See, for example, O'Toole, Stinson, & Moore, 2009). But it is timely to remember Boal,(Quoted in Moral-Barrigüetei & Guijarroii, 2022): “Art not only serves to teach how the world is, but “[…] also to show why it is like this and how it can be transformed” (Boal, 2011, p115). A drama exploration about the impact of farming practices on the Australian Great Barrier Reef, engages students with a significant climate change issue but it also necessarily involves students in the politics and competing passions of people. Drama teaching must take account of both challenging and conserving values and ideas.

Similarly, the texts we choose as we draw on the published literature of drama and theatre presents us with choices that can promote radical thought and challenges. The plays of Shakespeare, so often held up as the established cannon, also highlight teen rebellion (Romeo and Juliet) or the overthrowing of tyrants (Julius Caesar ). No text we choose (apart from the most bland) are values free. What interests us in great drama is how it brings ourselves face to face with ideas, people and situations where something is at stake, something matters. Without this we do not have conflict and dramatic tension. But as Heathcote usefully reminded us, in drama workshops we need to build on productive tension (O'Neill, 2014).

As drama teachers we walk the tightrope. Or swim in a pool of ambiguous possibilities.

Drama teacher education must be firmly situated within a values framework that recognises our responsibilities and balances them with our instincts to lead change. Drama teachers need an articulated philosophy of why and how they work – a Theoretical Framework. It is not enough to just recognise that drama is risky business but to know why it is and how we proceed to work in the world. Teaching is a refuge for pragmatists. Often, teaching is seen as atheoretical (a point I have often made about the way Australian Curriculum documents are presented to teachers). But none of us teach in a vacuum of ideas. We are the sum of our ideas of knowledge (epistemology), our world view (ontology), systems of beliefs (ideology) and our values (axiology), all contributing to our praxeology that links our actions and our thinking. The quality of our work as drama teachers lies in our knowing, being and doing.

To stay afloat in the infinity pool of drama education, we need always to know where we are and where we are headed. Without that, we risk moving towards another abyss – a loss of perceived relevance and we move towards that “the other side of the line”, becoming non-existent. We can be cast in the role of being “the other” in education. What we need to do is to challenge the most fundamental characteristic of abyssal thinking: the impossibility of the co-presence of the two sides of the line. We need to remind all that we are here, we have relevance and meet a human need. We do not belong beyond that perceived line, where there is only nonexistence, invisibility, non-dialectical absence (Santos, 2007). As we teach our students about acting – we must be both in the moment and out of the moment simultaneously. We must be in the pool eying infinity while keeping ourselves oriented to present reality. We must fight against being seen as invisible and ignored and, as a result, viewed as a “waste of time”.

1. Note: I was astounded to see in the suburbs of Washington DC in July 2022, a table in the Barnes and Noble Bookstore labelled Banned Books. Among them was one titled Drama (Telgemeier, 2012), a graphic novel about middle school students and a drama production. In some places it has been banned not for profanity, drug or alcohol use, or sexual content but because it includes LGBTQ characters.

Drama = Danger (in some eyes!)

References

Boal, A. (2011). Juegos para actores y no actores. Barcelona: Alba.

Brownstein, R. (February 15, 2022). Why schools are taking center stage in the culture wars.

Finneran, M. J. (2008). Critical Myths in Drama as Education. (Ph.D.). University of Warwick, Warwick.

Hunter, J. D. (1991). Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America. New York: Basic Books.

Landy, R. J. (2007). Drama therapy: Past, present, and future. In I. A. Serlin, J. Sonke-Henderson, R. Brandman, & J. Graham-Pole (Eds.), Whole person healthcare Vol. 3. The arts and health (pp. 143–163): Praeger Publishers.

Moral-Barrigüetei, C. d., & Guijarroii, B. M. (2022). Applied theatre in higher education: an innovative project for the initial training of educators. EDUCAÇÃO & FORMAÇÃO, 7(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.25053/redufor.v7i1.5528 https://revistas.uece.br/index.php/redufor/index

O'Neill, C. (2014). Dorothy Heathcote on Education and Drama: Essential Writing: Routledge.

O'Toole, J., Stinson, M., & Moore, T. (2009). Drama and Curriculum A Giant at the Door: Springer.

Pascoe, R. (June 09, 2020). Misconceptions about Drama Teaching. Retrieved from http://www.stagepage.com.au/blog/2020/6/9/misconceptions-about-drama-teaching

Santos, B. d. S. (2007). Beyond Abyssal Thinking: From Global Lines to Ecologies of Knowledges. Review, XXX(1).

Snyder, B. (2019). The Healing Power of the Arts - Drama Therapy and the Use of Theatre in the Treatment of Trauma. In: Student Scholar Symposium Abstracts and Posters. 370. https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/cusrd_abstracts/370.

Telgemeier, R. (2012). DRAMA: Scholastic/Graphix.