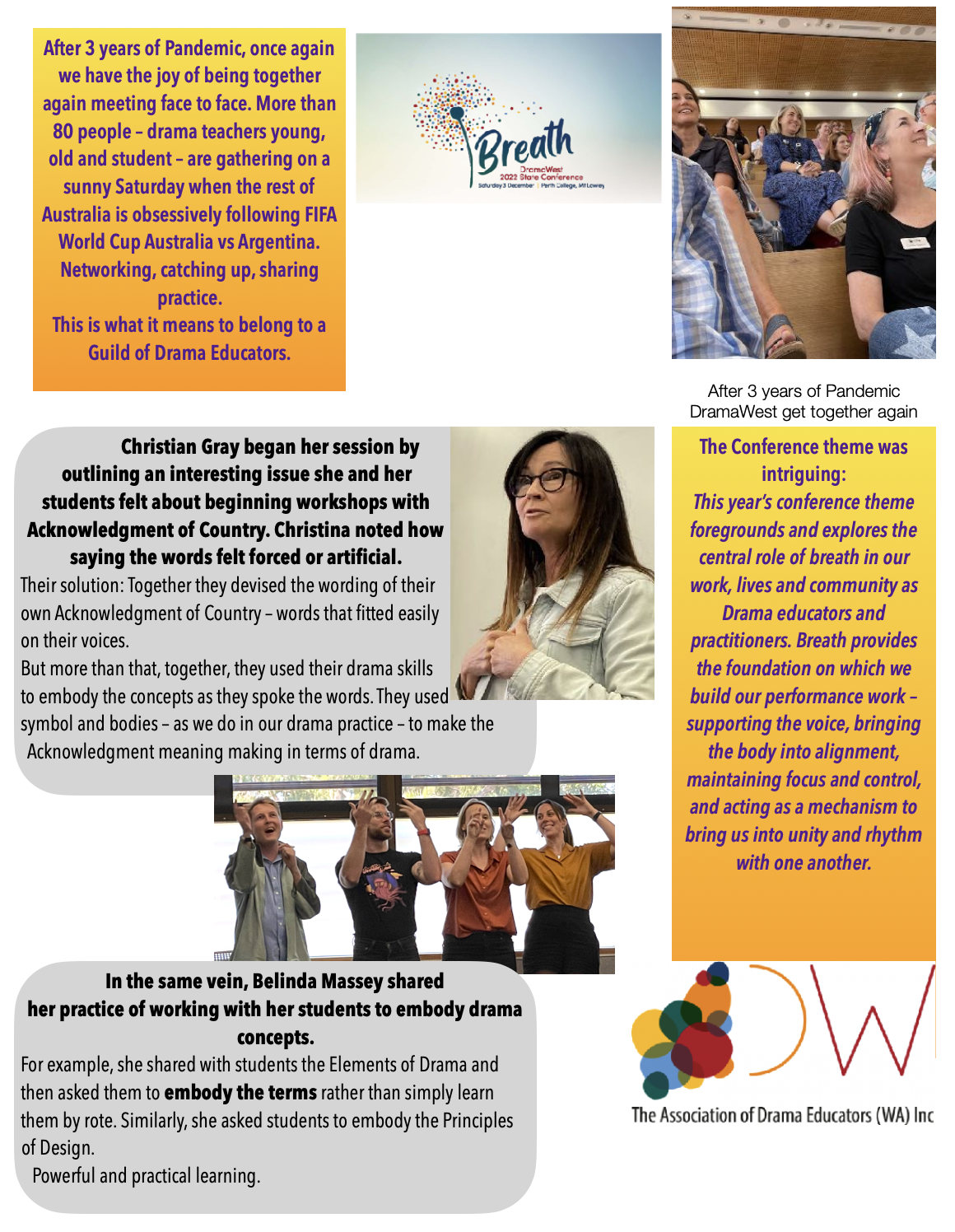

Drama Tuesday - DramaWest Conference 2022 (At Last)

/Planning drama activities that maximise student learning

The workshop by Danielle Miracle at the DramaWest Breath Conference provided a clear case for the need for drama teachers planning to link planning with stated student learning outcomes as set out in the mandated syllabus. The people around the table nodded wisely about the concepts of providing students with clearly articulated roadmaps for learning that made the connections with the syllabus. They seem in synch with the concepts of working from the “Big Picture”, using the “Scope and Sequence” providing a step by step “Layering of concepts progressively becoming more complex” (a “Spiral Curriculum”, though the term was not used) and ensuring that students were explicitly told the “Metalanguage” of the curriculum.

The workshop presenter then asked each group to work with a specific year group, specific syllabus, and talk through planning a unit of work. In doing so, she outlined how in her teaching in the UK, this sort of planning was linked directly to the teacher’s KPIs – Key Performance Indicators – and that your employment depended on planning delivering results. Schemes of Work are not just paperwork but accountability documents. That’s a significant shift in thinking about assessment – assessment and planning is usually considered as being about student achievement. On the other hand, this approach flips the focus to being on assessment of planning being about teacher performance. That clear sense of consequences is maybe something that is not built into local teaching in such clarity.

The group at my table began well: they identified that they would work with Year 10 and the form Youth Theatre. They added that they wanted to work with Brecht (foreshadowing the Upper Secondary course). They also agreed that the end point of the teaching unit would be a focus on a performance for a specific audience.

But the issue was: how to bridge the gap.

What are the steps - the layering of activities to get from the start to the end point?.

As I listened to the silence and the metaphoric shrugging of shoulders, it occurred to me that there was more fundamental issue: is there a lack of sufficient detailed knowledge about the form and the focus on Brecht. Teaching about Brecht has been simplified into a sort of shorthand: politics; a-Affect (because we don’t know how to say verfrumdungseffekt), don’t get emotional (not Stanislavsky), use posters/ captions/ placards, use song and dance, minimal sets, break the Fourth Wall.

They are valid points.

You can also do a quick scan of the Internet and find examples.

But how do you build connected teachable moments that at the end of the unit, leave students with enduring understanding to be able to apply Brechtian principles to their own drama creations?

Some ideas that might help with more detailed planning for this project

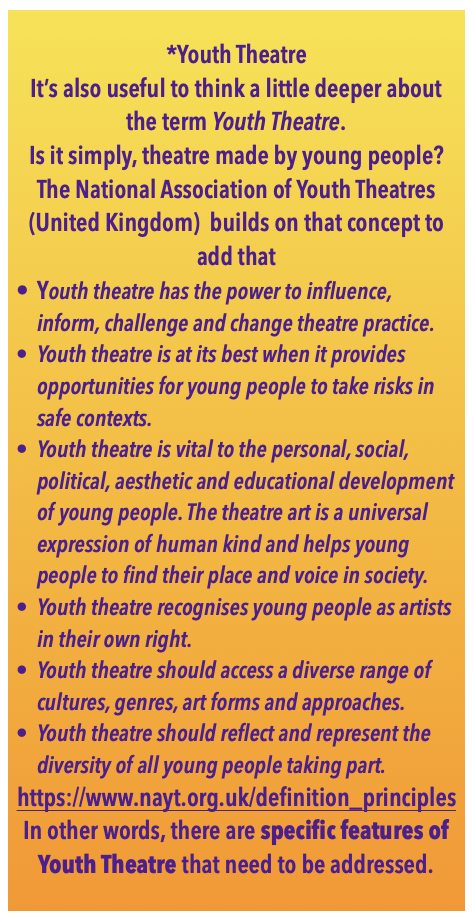

Brecht wrote a series of Lehrstücke. They would serve as useful role models for students. Working with plays such as He who says Yes and He who says No juxtaposed companion pieces side by side enables students to see how ideas are set up in dialectical oppositions. By looking at these as examples, we take the concept of some of Brecht’s ideas from the abstract to the specific – and particularly link to the concepts of Youth Theatre*.

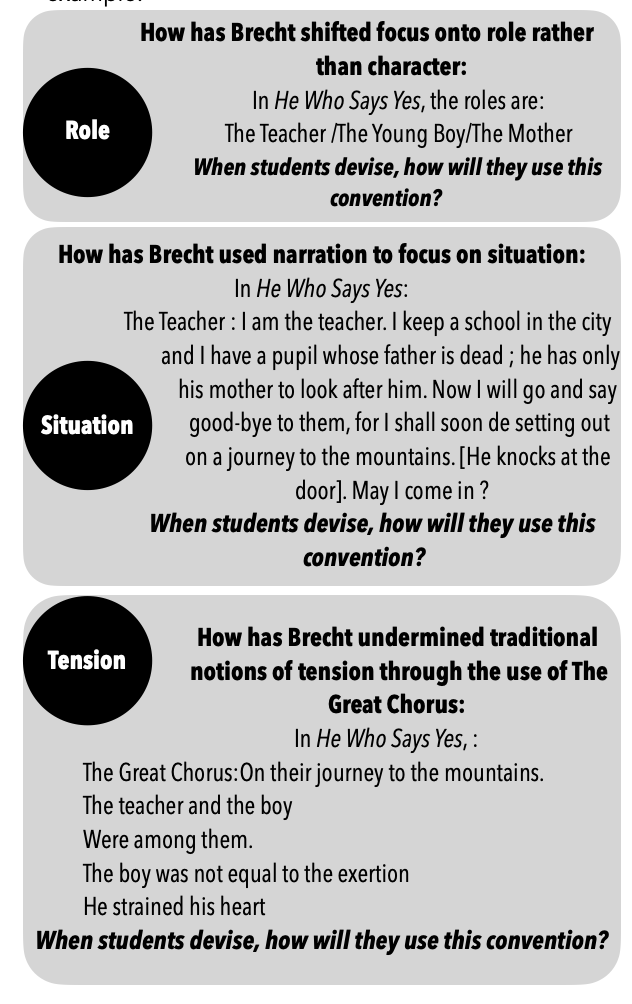

Link the planned learning to the concepts articulated in the Syllabus. For example, it would be possible to build a layered exploration around the concepts of role, situation, tension, symbol, space, time (see the Elements of Drama identified in the syllabus). For example:

How could you build on these ideas?

How could some “Backward Planning” help?

State specifically what you want students to show in the Youth Theatre project as a result of your teaching in the unit. In other words, not a generalised objective but a specific one: in this Youth Theatre project students will show collaborative planning in generating ideas, applying specific principles of Brechtian practice including …

But it is important to also step deeper than just this one unit of work.

How do we respond to these questions?

How do we help drama teachers build more specific knowledge about the forms and styles named in the syllabus?

How do we help drama teachers build beyond generalised telegraphed and sometimes half-understood markers of form and style? (How do they know more than the headlines about Brecht, for example, to being able to deliver the sort of detail implied by the shorthand of curriculum documents?

How do we shift notions of accountability?

Who is being accountable?

What is it that teachers are actually accountable for? And, why does this concept freak out some teachers?