Drama Tuesday - What will I teach today?

/It’s the question we face as teachers every day of our working lives?

What will I teach today?

Wouldn’t it be nice if there was a convenient text book to open and say to students, Look at page 53 and do what it says there.

Unlike many other school subjects, drama does not seem to have a simple answer or a single set of textbooks or set syllabus.

Many Curriculum frameworks and syllabuses are written in open-ended ways. We need to join the dots or fill in the missing gaps.

What are the choices and decisions that drama teachers need to make in their day to day planning?

How do know what to teach in drama? When to teach specific concepts and skills and processes?

How do I teach so students learn in ways that match or suit their age and stage of development?

To answer these questions we need to build a map in our head about how students learn drama at different ages and stages.

Teaching drama can’t just be a jigsaw of randomly chosen activities or a haphazard collection of things that work. They have to lead students somewhere. The word educate comes from the Latin deuce I lead forward.

We must have a curriculum compass that guides us forward in the learning of our drama students. One of the principles must be that we teach drama in ways that acknowledge and understand the ways youngsters learn at different ages. We need to teach with a sense of an underlying progression in learning.

The term learning progression refers to the purposeful sequencing of teaching and learning expectations across multiple developmental stages, ages, or grade levels. They provide concise, clearly articulated descriptions of what students should know and be able to do at a specific stage of their education.

Consider the simple yet complex notion of improvising which is the backbone of many drama teaching programs. what is or expectation of improvisation in children who are three and four? How do we shape learning experiences as they are five or ten or fourteen. We don’t expect 5 year olds to master the concepts of Algebra that they can learn in Year 12. But they do have things to learn in Year 1 so that they can learn in Year 12. There is a chain of connection across the learning years.

This is William, our grandson, in free play. This shows the seeds of improvisation that we develop through drama programs.

Where do we go next? How do we build learning upon learning?

What are aged and developmentally appropriate drama activities towards a growing learning about improvisation?

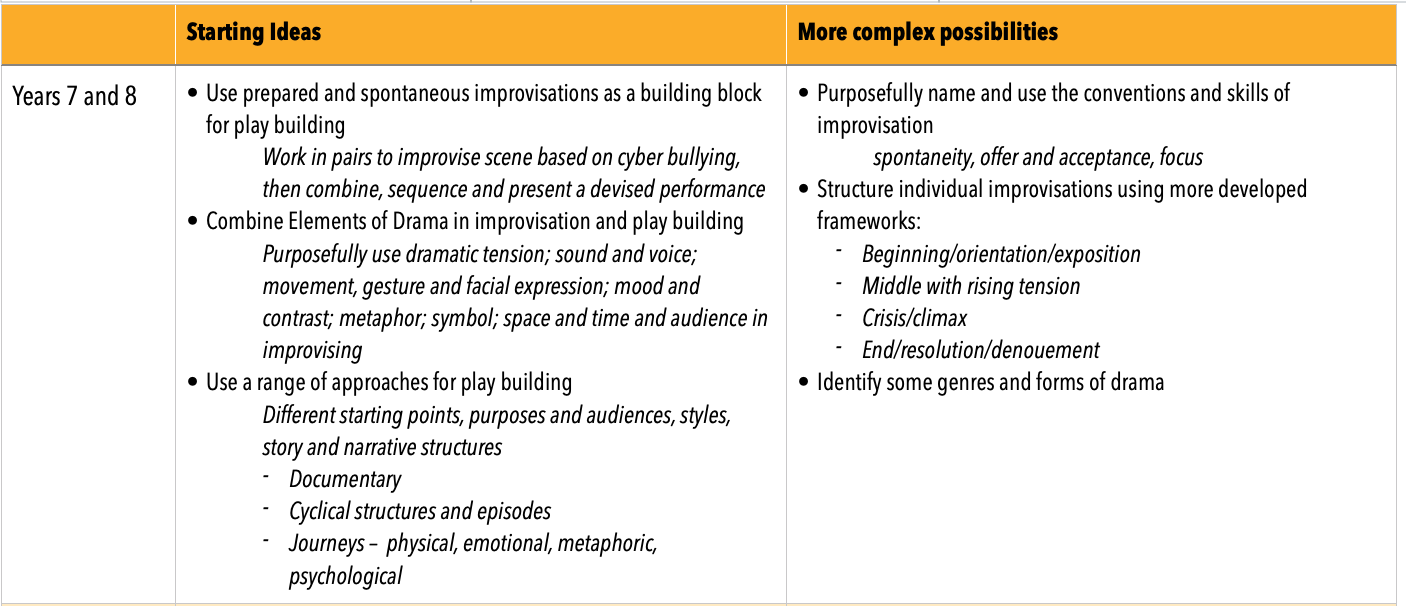

It is useful to visit again some of the learning progressions that have been developed as curriculum.

It might seem obvious, but nonetheless important, to observe that as children grow, their capacity to understand and apply concepts develop and our planning should reflect the patterns of child development.

The following example of a progression is based on some of my earlier research.

The Holy Grail of Drama Curriculum writers is to write workable progressions for development of drama across school years. It is notoriously difficult to write these progressions with ironclad certainty. They are at best useful approximations to guide. They are based on observation of young people learning drama and teacher experiences. But they are better than random guesses.

A final thought:

I have had a conversation once with a teacher who said – for efficiency – that she teaches the same lesson to all the different years across the school. One size fits all.

Can you spot the flaw in that approach?

What is the map that guides your choices as a drama teacher?