Drama Tuesday - A Fools Project

/Creating Performing Opportunities in Times of Lockdown

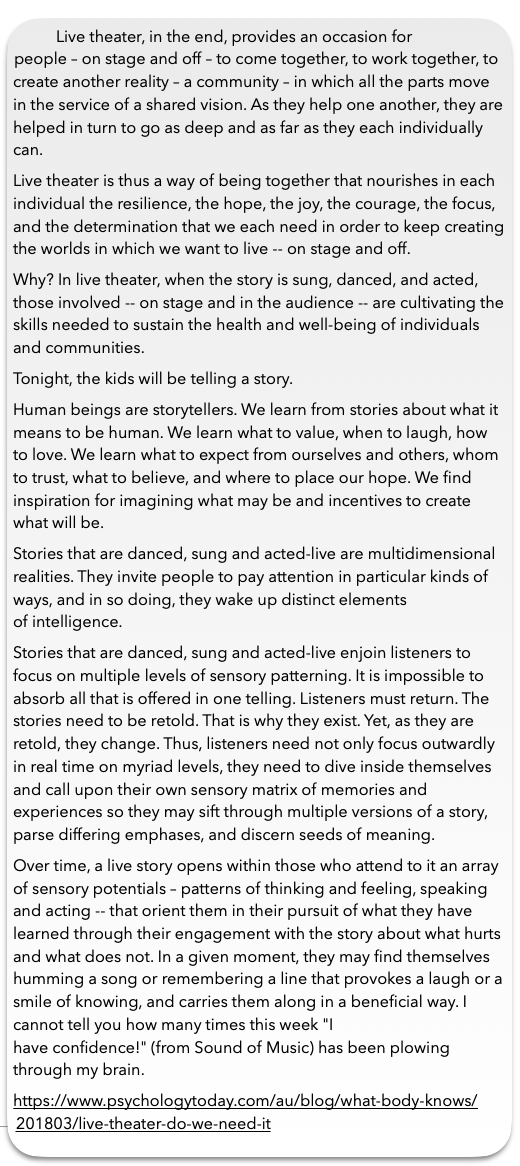

Lately I have been thinking about ways of generating drama projects for students in lockdown situations. My students need short scenes or plays that can be performed over digital platforms, if necessary, but which can also be rehearsed independently. There are many examples of compilation performances - Two that I particularly like are based on Shakespeare also: Appel, L. and M. Flachmann (1982). Shakespeare's Lovers: A Text for Performance and Analysis. Carbondale and Edwardsville, University of Southern Illinois. Appel, L. and M. Flachmann (1986). Shakespeare's Women: A Playscript for Performance and Analysis. Carbondale and Edwardsville, Southern Illinois University Press.

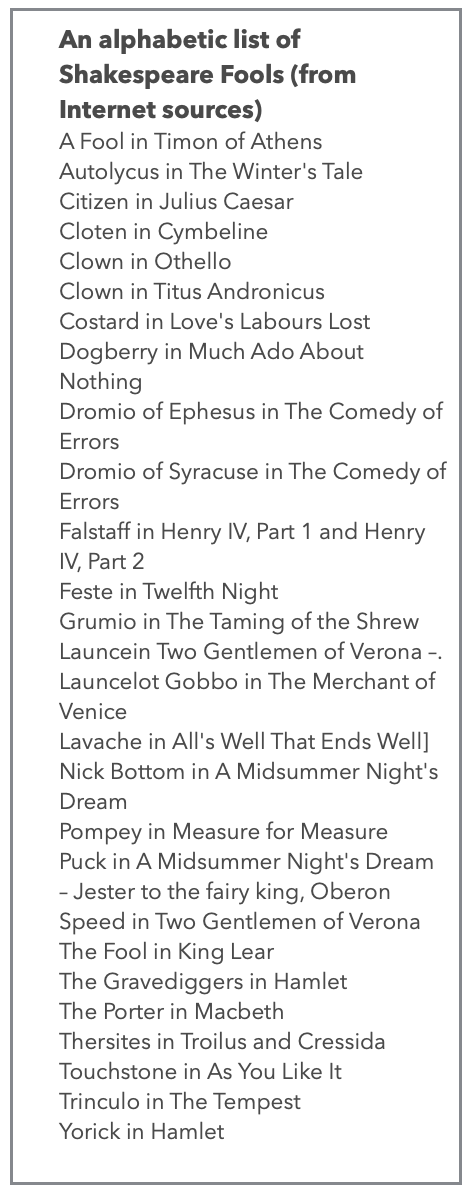

I started by thinking about all of Shakespeare’s Fools.

I conceptualised this project as a research and performance project. Students would need to research and write about the characters considered fools and their functions in the plays that included them. They would need to look at the research about the Shakespearean Fools. Then, they would identify a scene in which the Fool and others interact, make a suitable scene cutting, rehearse and perform it. Together as a whole class we would construct a devised project. This sounds like a sufficiently challenging and yet satisfying project.

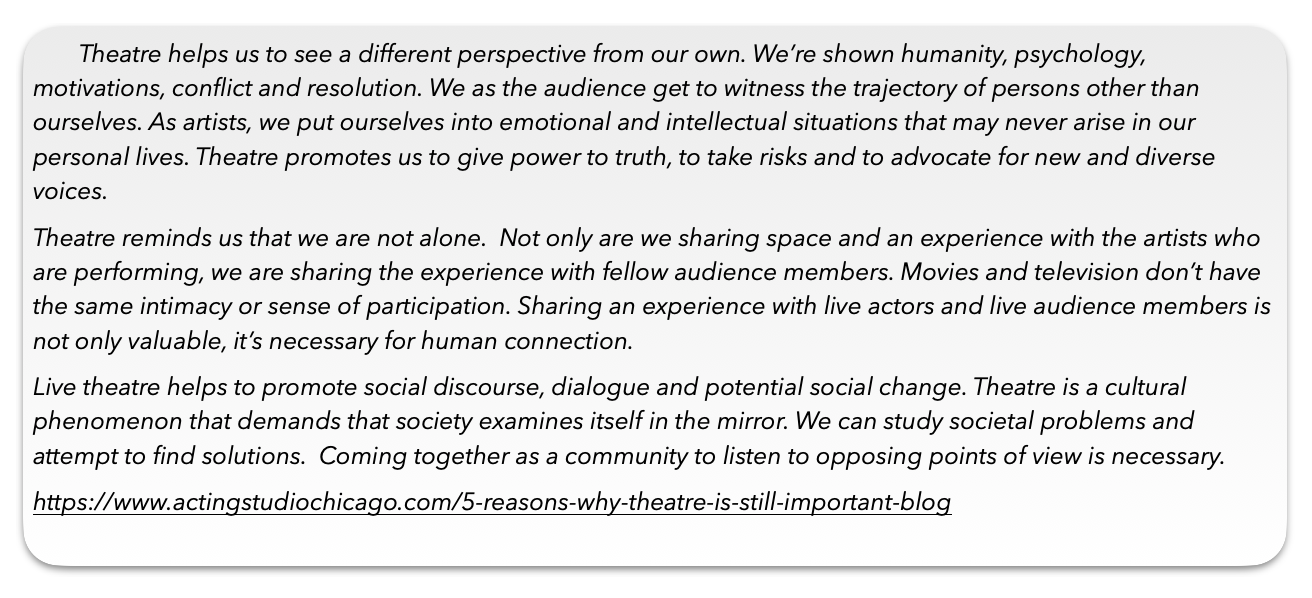

The Shakespearean fool is a recurring character type in his plays. These characters were most often common people who had the wit and skill to make fun of upper class people. Often seen as “comic relief” to the more serious aspects of a play, it is worth considering that the Fools in Shakespeare provide an emotional depth and contrast to the serious themes. By shifting from the distanced world of the drama to more domestic and familiar scenes, the complexity of the dramatic situation is heightened. 'That, of course, is the great secret of the successful fool – that he is no fool at all.’ (Asimov 1978)

Jan Kott, in Shakespeare Our Contemporary ,

“The Fool does not follow any ideology. He rejects all appearances, of law, justice, moral order. He sees brute force, cruelty and lust. He has no illusions and does not seek consolation in the existence of natural or supernatural order, which provides for the punishment of evil and the reward of good. Lear, insisting on his fictitious majesty, seems ridiculous to him. All the more ridiculous because he does not see how ridiculous he is. But the Fool does not desert his ridiculous, degraded king, and accompanies him on his way to madness. The Fool knows that the only true madness is to recognise this world as rational.”

From a BBC April Fool’s Day Report:

Shakespeare loved a fool and not just on 1 April. He used them in most of his well-known plays, but who would their equivalents be today?

It was never about bright clothes, eccentric hats and slippers with bells on them. Shakespeare’s fools were the stand-ups of their day and liked to expose the vain, mock the pompous and deliver a few home truths - however uncomfortable that might be for those on the receiving end.

"Shakespearean fools, like stand-ups today, had a licence to say almost anything," says Dr Oliver Double, who teaches drama at the University of Kent and specialises in comedy. "It was an exalted position."(Winterman 1 April 2012)

In his book The Guizer Alan Garner (1975)tells us,

If we take the elements from which our emotions are built and give them separate names, such as Mother, Her, Father, King, Child, Queen, the element that I think marks us most is that or Fool, It is where our humanity lies.

The Fool is full of contradictions, as we are. He is at once creator and destroyer, bringer or help and harm. Through his mistakes we learn how to do things properly. He is the shadow that shapes the light.

Putting on the Motley.

The costume and props of the Fool were – according to reports of the times – standardised. A patchwork and ragged coat, sometimes with bells hung on it. Breeches of different coloured legs and a mono like hood and cloak decorated with animal body parts such as donkey’s ears and rooster heads. The prop was a stick decorated with a doll head or a fool. A pouch filled with powders, sand, peas or air filled out the outfit.

Some useful resources

The No Sweat Shakespeare Blog: The Ultimate Guide To Shakespeare’s Fools

https://www.nosweatshakespeare.com/blog/ultimate-guide-shakespeares-fools/

The British Library Shakespeare’s Fools

https://www.bl.uk/shakespeare/articles/shakespeares-fools

OUP Shakespeare’s clowns and fools [infographic]

https://blog.oup.com/2016/09/shakespeare-clowns-fools-infographic/

But there are many more.

Bibliography

Appel, L. and M. Flachmann (1982). Shakespeare's Lovers: A Text for Performance and Analysis. Carbondale and Edwardsville, Univsersity or Southern Illinois.

Appel, L. and M. Flachmann (1986). Shakespeare's Women: A Playscript for Performance and Analysis. Carbondale and Edwardsville, Southern Illinois University Press.

Asimov, I. (1978). Asimov's Guide to Shakespeare,Vols.1-2. New York, Gramercy Books.

Garner, A. (1975). The Guizer. London, Hamish Hamilton Ltd/William Collins Sons and Co Ltd.

Kott, J. (1964). Shakespeare: Our contemporary. Garden City, N.Y, Doubleday.

Winterman, D. (1 April 2012). "Shakespearean fools: Their modern equivalents."