Drama Teacher Education – got my ticket for the long way round

/Drama Teacher Education in Australia is at crossroads.

For the Vision 2020 National Drama Conference due in Brisbane in April 2021, I re-worked my workshop presentation as a video and share it here.

The presentation draws on a chapter I have been writing and re-writing since 2020 for the Routledge Companion to Drama Education edited by Peter O’Connor and Mary McEvoy (forthcoming after a long delay caused by the Coronavirus COVID-19 Pandemic – another of the many pivots that have happened 2020-2021).

The text of the presentation is also included.

It is also published in the Digital library for the Conference that Drama Queensland has put together.

https://www.dramaqueensland.org.au/pd/conference/

Video Script

Drama Teacher Education – got my ticket for the long way round

Drama Teacher Education in Australia is at crossroads.

Robin Pascoe

Honorary Fellow, College of Science, Health, Engineering and Education (SHEE), Murdoch University, South Street, Murdoch, Western Australia 6150

Introduction

Drama Teacher Education in Australia is at another crossroads. Drama teacher education emerging within formal university structures in the mid 20th century until now has been a remarkable success story. But there is rapid and concerning change. Indicative of changes in other universities, 2019 was the last time that Drama Teacher Education Secondary was offered at Murdoch University. There are similar signs of contraction in other drama courses across Australian universities

Context: developing a drama teacher education course

I have spent the last 20 years teaching drama education beginning with asking colleagues fundamental questions:

What do you want teachers to know and be able to do on Day 1? And every day after that?

Over time I developed an approach based on the following principles:

We learn to teach Drama in the way that we learn drama

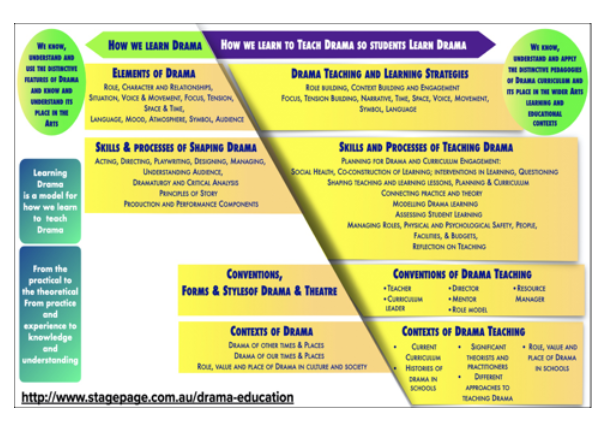

To teach Drama effectively we develop two inter-related perspectives: how we learn Drama and how we teach so students learn Drama. They are connected ways of thinking, doing and being a drama teacher.

We learn Drama through experience, observation, modelling and being part of an ensemble. We learn to teach Drama through applying our direct experiences of drama and theatre; observing and modelling from others teaching drama; and, belonging to a community of shared practice (what I sometimes call a Guild of Drama Teachers).

In Learning Drama, we identify the distinctive nature of Drama/Theatre as an art form and its role in people’s lives, society and community. We learn Drama by making Drama recognising that it is hands-on, practical and experiential. It is embodied learning that brings together our body, mind and spirit. We understand that

Drama is aesthetic experience contextualised in the art forms’ histories, conventions and cultures.

In Learning to Teach Drama, we identify Drama as curriculum. We shape our practice in our Drama Teacher roles as teacher, curriculum leader, director, mentor, role model and resource manager.

Learning to teach Drama is practical, embodied experience. We learn to teach Drama by teaching Drama – by trying out strategies, concepts and approaches that help us refine our choice making as teachers.

In practice, this translated into an articulated course (Example available at http://www.stagepage.com.au/drama-education).

Conceptual learning was integrated into and followed practical experience. Hands on, practical examples of strategies, skills and processes were underpinned by connections with contexts, curriculum, theory, theorists and history. Key multiple roles of teaching drama – teacher, curriculum leader, director, mentor, role model and resource manager – were modelled and taught.

The current crisis

Drama teacher education in Australia began to be recognised in the 1960s. In Western Australia for example, in 1974 I was in the first intake of students permitted to take Drama Education as a major curriculum study at the Secondary Teachers College. The course outlined earlier was established in 2002 as the third available in Western Australia. As drama education grew in Western Australian schools (particularly with recognition of Drama ATAR in 1999) there has been a steady need for drama teachers. But there has been rapid and concerning change in the twenty-first century in the complex contemporary landscape of Australian universities.

In the past ten years or so there have been more than forty inquiries into different aspects of teacher education (Mills & Goos, November.13.2017). The Australian Government Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group (TEMAG) reported in Action Now: Classroom Ready Teachers (December 2014) issues and concerns. There is a populist tabloid perception that teacher education is flawed if not failing (see, for example, Shine, 2018). This, in turn, has led to intense politicised scrutiny and regulation including Accreditation of Initial Teacher Education Programs in Australia (AITSL, 2011) and the establishment of Australian Professional Standards for Teachers (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL), 2017). Yet, the situation is not clear cut.

Trends and patterns There has been an erosion of drama teacher education at my university over time and diffusion of focus in other Universities.

What is happening for drama teacher education is more than a response to the Coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic. There is a significant challenge to place of drama teacher education itself. To move beyond this moment, we need to better understand some deeper underlying issues.

Recognising the abyssal line

It is too easy to sound a warning about declining standards in drama teacher education. The tree that holds up the sky is uneasily still holding for us.

But as teacher educators in a contemporary world ,we have come to recognise “the abyssal line” (Santos, 2007), an invisible and unspoken line of presences and absences dividing worlds and world views into “us” and “them”. Things, people, ideas beyond that line are de-emphasised to the point that they are rendered null (in an Australian context, a terra nullius). This side of that line is what we collectively value, what we collectively think is important. In the eyes, minds and assumptions of many others both educators and the wider community, arts education is rendered as “other”, “peripheral”. Drama is negated, obscured, overlooked and rendered invisible, unimportant or non-essential (e.g., in course offerings in schools it is “optional”). When the dominant approaches to education consign arts education to this nether world, we have institutionalised “epistemicide” (Paraskeva, 2016) - a war on the knowledge(s) that we value, the destruction of existing knowledge and denial the possibilities of new knowledge(s).

To put it bluntly, what we believe in is not shared by many.

There continue to be many misconceptions about drama teaching.

Now more than ever we need as a drama education community to re-articulate our beliefs and values about drama education.

A robust schema for Drama Teacher Education

Whatever approach is taken to drama teacher education, there needs to be an underlying robust, durable, practical schema to serve as a living and responsive guide to our work.

Learning to teach drama focuses on embodied learning in the arts (Bresler, 2004). Through practical, hands on experiences in the drama we model the ways that your students learn the arts and ways that you teach the arts. This engenders embodied teaching.

This approach is based on sound research about providing:

analogue experiences – analogue experiences are like the ones students in drama experience; providing teachers with similar learning experiences that they need to facilitate for their students (Hilda Borko & Ralph T. Putnam, 1995; Morocco & Solomon, 1999)

content focus – unambiguous content description (Desimone, Porter, Garet, Yoon, & Birman, 2002; S.Garet, Porter, Desimone, Birman, & SukYoon, 2001; Shulman, 1986)

active learning – where teachers are engaged in the analysis of teaching and learning; learning from other teachers and from their own teaching; reviewing examples of effective teaching practice (Desimone et al., 2002; Franke, Carpenter, Fennema, Ansell, & Behrend, 1998; Franke, Fennema, & Carpenter, 1997; Morocco & Solomon, 1999; S.Garet et al., 2001)

dialogue amongst teachers – belonging to a community of drama teachers participating in discussion with practicing teachers (T. R. Guskey, 1986; T.R. Guskey, 2003; Virginia Richardson, October 1990)

long term support and feedback – support beyond the immediate experiences in the workshop through enrolling in community of drama teachers (H. Borko & R.T. Putnam, 1995; T.R. Guskey, 2002)

This is an articulated theoretical framework for drama teacher education course design that steps beyond pragmatic functionalism. It is a framework informed by Dewey, Vygotsky, Bruner, Eisner, Greene and others. Learning to teach drama involves acts of purposeful meaning making that draw together personal experiences and those of others (Dewey, 1938:2005; Eisner, 2002). No one learns alone – drama is intrinsically social learning (Grumet, 2004; Vygotsky, 1978). Drama teachers learn cognitively, somatically and affectively – mind, body and spirit (Peters, 2004). They work with enactive, iconic and symbolic modes (Bruner, 1990). Learning to teach drama engages aesthetic imagination (Greene, 1995). Learning to teach drama involves proactive participation in communities of practice (Wenger, 1998). Learning to teach drama organises drama knowledge, categorise it and uses strategies of paradigmatic thinking and narrative building (Bruner, 1991).

Every Drama Teacher needs a robust schema for what they are doing and why as the experienced drama teacher in the focus group articulated.

Peter Wright and I have written recently about Arts Teacher Education as Applied Aesthetic Understanding (in press) (adapted and extended from (Wetterstrand, 1999). Students need to:

see themselves as creators – as emerging artists beginning to develop understanding and control of specific skills and processes in drama

see themselves as thinking and engaging aesthetically. They critically engage with their own experiences and those of others

speak the language of the art form

display the habits of mind of artists and build cognitive and practical structures for managing their learning and teaching drama

build personal identity through drama and develop personal, social and cultural agency – capacity to initiate, manage and forge their own meaning making

develop perspective and a range of practical and informed understandings rather than take a simple unitary view of drama teaching

extend and deepen their understanding of the characteristics of drama as an art form and drama in the service of learning

reflect on their processes, products and their own learning in, through and about drama – and, beyond that, to human experience itself.

At the heart of it the developing drama teachers need capacity to cope with the sometimes stressful and always demanding work of teaching drama. They need to become reflective practitioners understanding and managing their multiple roles. All of which is underpinned by their practical knowledge, understanding of the skills and processes of the art form of Drama

An important point was made by an experienced teacher who was part of my initial focus group:

young teachers need to have an articulated philosophy of drama teaching. They must be clear about why they want to be a drama teacher. Their ultimate success as drama teachers relies significantly on their values about drama and about teaching. They needed a capacity built on respect, collaboration, working through process as well as product.

Conclusion

I don’t think I realised just how long the drama education journey would be when I entered that course in 1974. I got my ticket for the long way round.

There’s a song that’s an earworm in my life at the moment. I think its emblematic for a life in drama teacher education.

I got my ticket for the long way round

Two bottles of whiskey for the way

And I sure would like some sweet company

And I'm leaving tomorrow, what do you say

(Simone, 2013)

Drama teacher education and drama education itself, is a long-term project. There’s a need for a long view perspective. We are here for the long haul. Drama education and drama teacher education will survive the current road bumps. We will emerge a little shaken and stirred. But we must not lose sight of the long view and the challenges of helping those who make decisions to step over the abyssal line. Or that we as drama educators need in this time and into the future to walk both sides of that line.

The need for the robust schema outlined earlier is urgent and essential. Drama teacher education curriculum is not just content knowledge. It embodies ways of knowing and being in the world. It is too easy to play the misunderstood victim role as contexts change. It is necessary for us to strategically acknowledge and disarm critics and move past obstacles. It is insufficient to simply assert our place in the educational sun; we need to make the case with robust research based on experience that is not merely confirming the past but engaging future possibilities.

While I continue to work towards the long-term goals outlined, I know that this is not the task of one person and that at some point we all need to pass the baton to another generation. Long after I am gone, the case needs to be argued. We need to build drama teacher education as inevitable, as a self-evident truth.

References

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL). (2017). Australian Professional Standards for Teachers. Retrieved from https://www.aitsl.edu.au/teach/standards

Borko, H., & Putnam, R. T. (1995). Expanding a Teachers’ Knowledge Base: A Cognitive Psychological Perspective on Professional Development. In T. R. Guskey & M. Huberman (Eds.), Professional Development in Education: New Paradigms and Practices (pp. 35-66). New York: Teachers College Press.

Borko, H., & Putnam, R. T. (1995). Expanding a teacher’s knowledge base: A cognitive psychological perspective on professional development. In T. R. Guskey & M. Huberman (Eds.), Professional Development in Education. New York: New York: Teachers College Press.

Bresler, L. (2004). Knowing Bodies, Knowing Minds - Towards Embodied Teaching and Learning. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of Meaning. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bruner, J. (1991). The Narrative Construction of Reality. Critical Inquiry, 18(1), 1-21. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1343711

Desimone, L. M., Porter, A. C., Garet, M. S., Yoon, K. S., & Birman, B. F. (2002). Effects of Professional Development on Teachers' Instruction: Results from a Three-Year Longitudinal Study. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 24(2 (Summer 2002)), 81-112. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3594138

Dewey, J. (1938:2005). Art As Experience: Perigee Trade.

Eisner, E. W. (2002). What can eduction learn from the arts about the practice of education? John Dewey Lecture for 2002, Stanford University. Retrieved from www.infed.org/biblio/eisner_arts_and_the_practice_or_education.htm . Last updated: April 17, 2005.

Franke, M., Carpenter, T., Fennema, E., Ansell, E., & Behrend, J. (1998). Understanding teachers’ self- sustaining, generative change in the context of professional development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 14(1), 67-80.

Franke, M., Fennema, E., & Carpenter, T. (1997). Teachers creating change: Examining evolving beliefs and classroom practice. In E. Fennema & B. Scott-Nelson (Eds.), Mathematics teachers in transition (pp. 255-282). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Greene, M. (1995). Releasing the Imagination: Essays on Education, The Arts and Social Change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Grumet, M. (2004). No one learns alone. Putting the arts in the picture: Reframing education in the 21st century, 49-80.

Guskey, T. R. (1986). Staff development and the process of teacher change. Educational Researcher, 15, 5-12.

Guskey, T. R. (2002). Professional development and teacher change. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 8, 381-391.

Guskey, T. R. (2003). What makes professional development effective? Phi Delta Kappan, 84(10), 748-750.

Mills, M., & Goos, M. (November.13.2017). Three major concerns with teacher education reforms in Australia. Retrieved from https://www.aare.edu.au/blog/?p=2548

Morocco, C. C., & Solomon, M. Z. (1999). Revitalising professional development. In M. Z. Solomon (Ed.), The diagnostic teacher: Constructing new approaches to professional development (pp. 247-267). New York: Teachers College Press.

Paraskeva, J. (2016). Curriculum epistemicides. New York: Routledge.

Peters, M. (2004). Education and the Philosophy of the Body: Bodies of Knowledge and Knowledges of the Body. In L. Bresler (Ed.), Knowing Bodies, Moving Minds - Towards Embodied Teaching and Learning. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

S.Garet, M., Porter, A. C., Desimone, L., Birman, B. F., & SukYoon, K. (2001). What Makes Professional Development Effective? Results From a National Sample of Teachers. American Educational Research Journal. doi:https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312038004915

Santos, B. d. S. (2007). Beyond Abyssal Thinking: From Global Lines to Ecologies of Knowledges. Review, XXX(1).

Shine, K. (2018). Everything is negative’: Schoolteachers’ perceptions of news coverage of education. Journalism. Retrieved from https://espace.curtin.edu.au/bitstream/handle/20.500.11937/70003/267577.pdf

Shulman, L. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4-14.

Simone, J. (2013). Cups (You're Gonna Miss Me When I'm Gone). In.

Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group (TEMAG). (December 2014). Action Now: Classroom Ready Teachers. Retrieved from https://docs.education.gov.au/system/files/doc/otheraction_now_classroom_ready_teachers_print.pdf

Virginia Richardson. (October 1990). Significant and Worthwhile Change in Teaching Practice. Educational Researcher, 19(7), 10-18. doi:10.2307/1176411

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wetterstrand, G. (1999). Creating Understanding in Educational Drama. In C. Miller & J. Saxton (Eds.), Drama and Theatre in Education International Conversations. Victoria B.C.: American Educational Research Association Arts and Learning Special Interest Group and the International Drama in Education Research Institute July308 1997 Victoria, B.C. Canada.