Drama Tuesday - Antidote

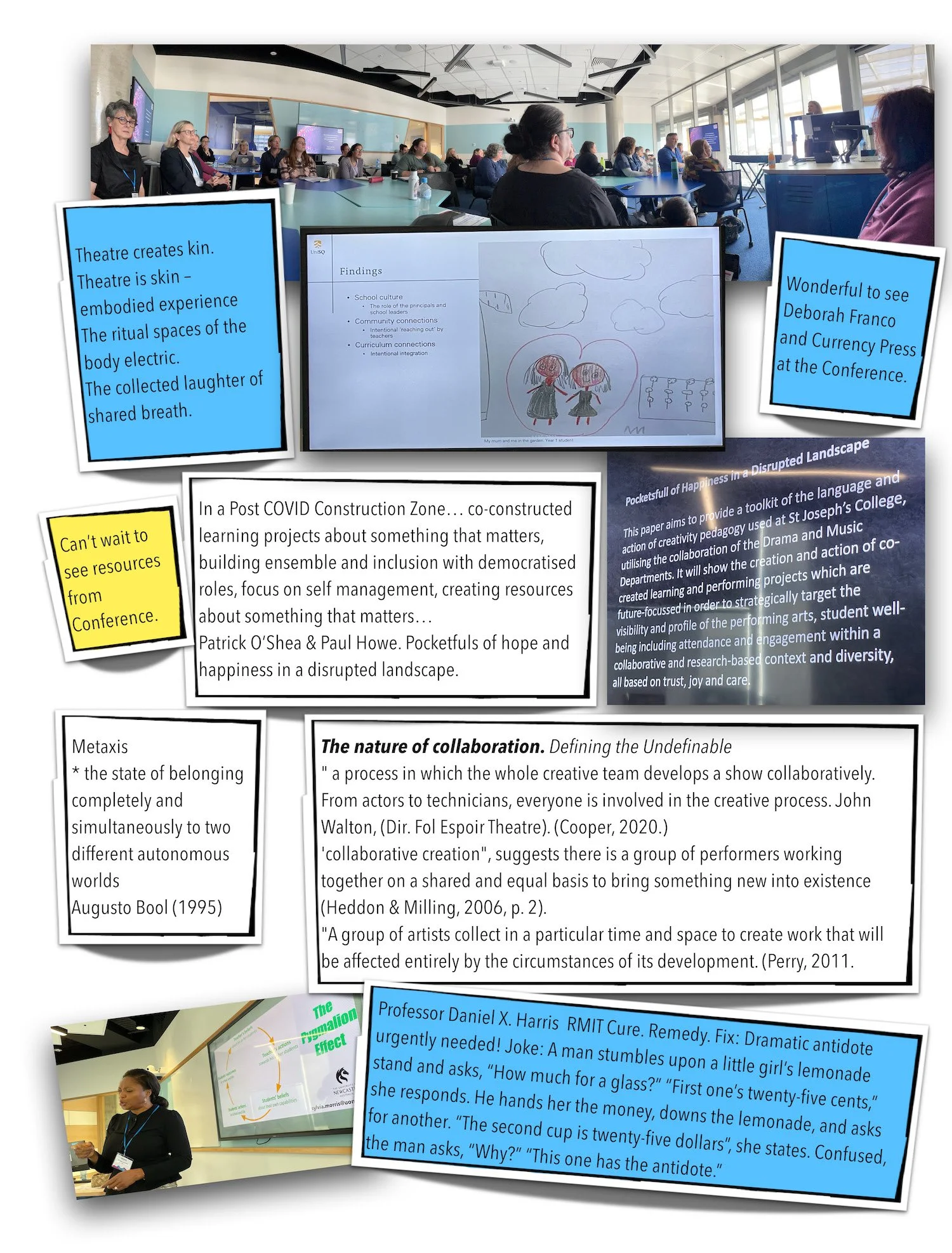

/Drama Australia National Conference June 2-3 2023, Newcastle. University of Newcastle

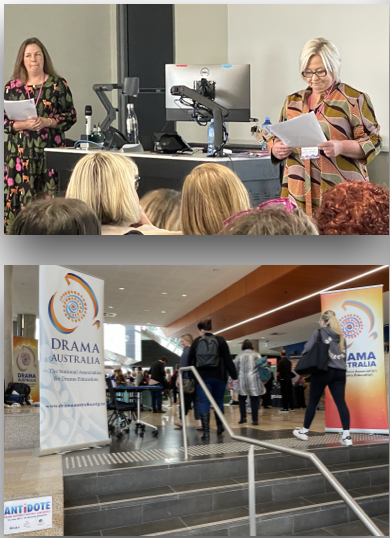

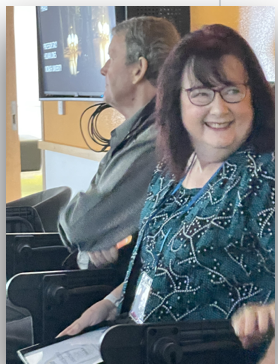

Excited to be at the Opening of Antidote the 2023 Drama Australia Conference at University of Newcastle in New South Wales, Australia. Conference Director Christine Hayton (also an IDEA Elected Officer and member of the Drama Australia Board) welcoming us to the University of Newcastle.

It’s wonderful to be back face to face. Last time we were physically together was in Melbourne November 2018. A long time between drinks. So excited to be with colleagues and friends.

The UON building is located on Hunter Street in downtown Newcastle. So many rich experiences to think about from a live in-person conference.

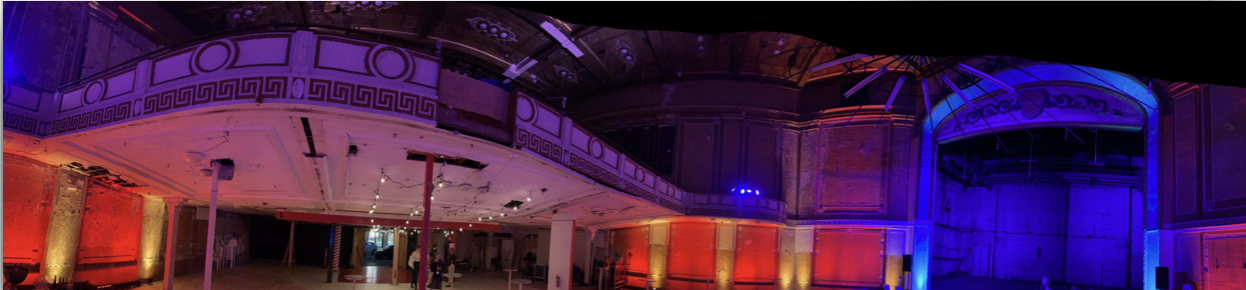

Day 1 Bookended by thinking about Popular Entertainment

The Opening Keynote by Associate Professor Gillian Arrighi (UNSW) posed the question: What is it with Popular Entertainments? Researcher on Australian popular culture with a focus on the Victoria Theatre in Newcastle, the keynote challenged drama educators to think about why drama curricula give precedence to Western European legitimised theatre over the popular entertainments of music hall, magicians, singers, tap dancers and animal shows. Gillian shared with us provocations from her course with students where they were required to research responses to exploring what popular entertainment offer to drama educators.

The end of the day was a reception at the Victoria Theatre in Newcastle where we were regaled with popular entertainments and plied with wonderful food and drink. The entertainments were provided by Anna Gambrill (they/them) aka King Chad Love is a Sydney-based Drag King, Joel Howlett, Magician and a bevy of others including conference attendees. Much joviality and fun.

I was entranced by the Victoria Theatre and will write another post about the experience.

There’s more information on the Victoria Theatre available at https://www.victoriatheatre.com.au/home .

Celebrating and thanking

Drama Australia owes a huge debt of thanks to Christine Hatton and Kelly Young, Conference Directors. Thank you. Also, it is important to say that DA Board members were everywhere introducing papers and speakers, corralling the cats, making sure everyone had a good time.

It was also a privilege to witness Christine’s paper (with Amy Gill) Reclaiming our estranged youth: Drama as a remedy for fractured belonging. Moving.

Drama Australia President’s Award

Colleen Roche

Congratulations to Colleen Roche, former President of Drama NSW and Drama Australia who is the 2023 recipient of the Drama Australia President’s Award in recognition for service to drama education. Colleen also serves on the IDEA Executive Council.

Thinking about Conferences Post-COVID-19.

Being in a live conference also set me thinking about how things have changed and are changing. When NADIE (which preceded Drama Australia) was founded its charter was to run national conferences in all of the states of Australia. In 2023, Drama Australia faced a dilemma: the hosts of the conference signalled early in 2023 that they were feeling overwhelmed at the prospect of hosting and Christine Hatton and the DA board stepped into the breach and took on the role. I am reminded of Liz’s experience with ANATS, the singing Teacher Association, whose National Board took on a similar tole when a conference was held in Hobart, Tasmania and the local association was very few in numbers.

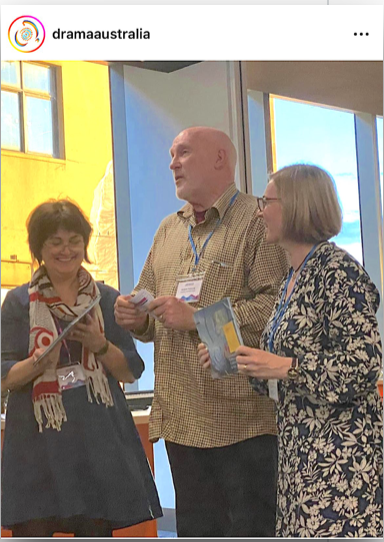

Presenting IDEA book on behalf of IDEA President Sanja Krsmanović Tasić to Drama New Zealand President Annette Thomson and Jo Raphael, DA President

Is the prospect of running a national conference too overwhelming for stretched and hard working drama teachers? At an international level, is there a similar dilemma for IDEA? The financial, organisational and personal cost of running conferences is dauntingly huge. There’s also a changing climate of support from schools and universities about attending conferences (Registration for this 2 day event was $450.00; we were well fed and looked after but cost is still an issue). And, the issue of providing hybrid and on-line versions enters the frame. Interestingly, the decision for this conference was to not offer an online option [IDEA2022 Congress convenors also wanted that Congress to be mainly in person and had limited online offerings].

Is the day of the full conference experience over?

Are we recalibrating the model of unperson sharing of practice and research?

Following a similar train of thought, it is also important to think about digital publishing. This Conference had online program – but did not take the step into the conference app world where everything is online (which ANATS has done using Whova).

There will be made available a collection of artefacts from the conference, from papers, etc.

Is it time to take the step further? The world is changing.

Small enthusiastic contingent from Perth. Brooke, Felicity and Jess.

Questions to be thought about for the next Conference – a joint Drama New Zealand and Drama Australia Conference in September 2024.

So many other observations to make.

More to write and think about.

For now, safely home (through a rain bomb over Perth Airport).

Drama Tuesday - Drama education shape shifting

/Reflection from the Drama Australia National Conference June 2-3 2023.

Drama is a shape shifter. Not quite in the dictionary meanings but in the sense that in drama when we take on role, we shift into the role.

I was struck by thinking about this during the Drama Australia conference over the weekend. It’s not necessarily a new thought but one to explore in this moment.

Drama teachers are adept share shifters.

When the drums of literacy beat, drama teaching shifts focus to bring to the foreground how drama supports language learning and use. When there is a focus on life skills, we assert the role of drama in building confidence. Drama claims a space in STEAM education with slick speediness. We hear calls for arts integration as the solution to the crowded curriculum and drama as a method. Feminist concerns remind us of the power of drama in raising issues. Similarly, as the currency of indigenous or First Nations inclusion increases, we need the reminders of the value of drama in that field.

That is not to say argue against a need for greater diversity in drama education.

Maybe this is a mechanism for coping with a search for reassuring relevance. Maybe it’s also politically savvy. In all of this soft shoe shuffling however, it is important to never lose sight of what drama is fundamentally and why it is a necessary part of a complete education. We need to remind ourselves that as each competing priority rings its bell, drama education is not just a vehicle for the topical or the passing educational pinup. We need to be alive to how the dominating voices are swamping or taking up all the available oxygen for arts education. We need to be true to the fundamental nature and purpose of drama education. In a world twisting and shaping itself to meet shifting educational fads, we need to plant our feet on the stage and deliver our lines with firmness.

Drama is wily. Drama is clever. Drama is political and social and cultural. Drama is all these things and we in drama education have learnt the lesson well. But drama education needs to be true to its purpose.

I know these can be seen as controversial thoughts. It’s not my intention to upset applecarts or to disrupt the parade. But sometimes these rebellious thoughts need a place in the conversation.

What do you think?

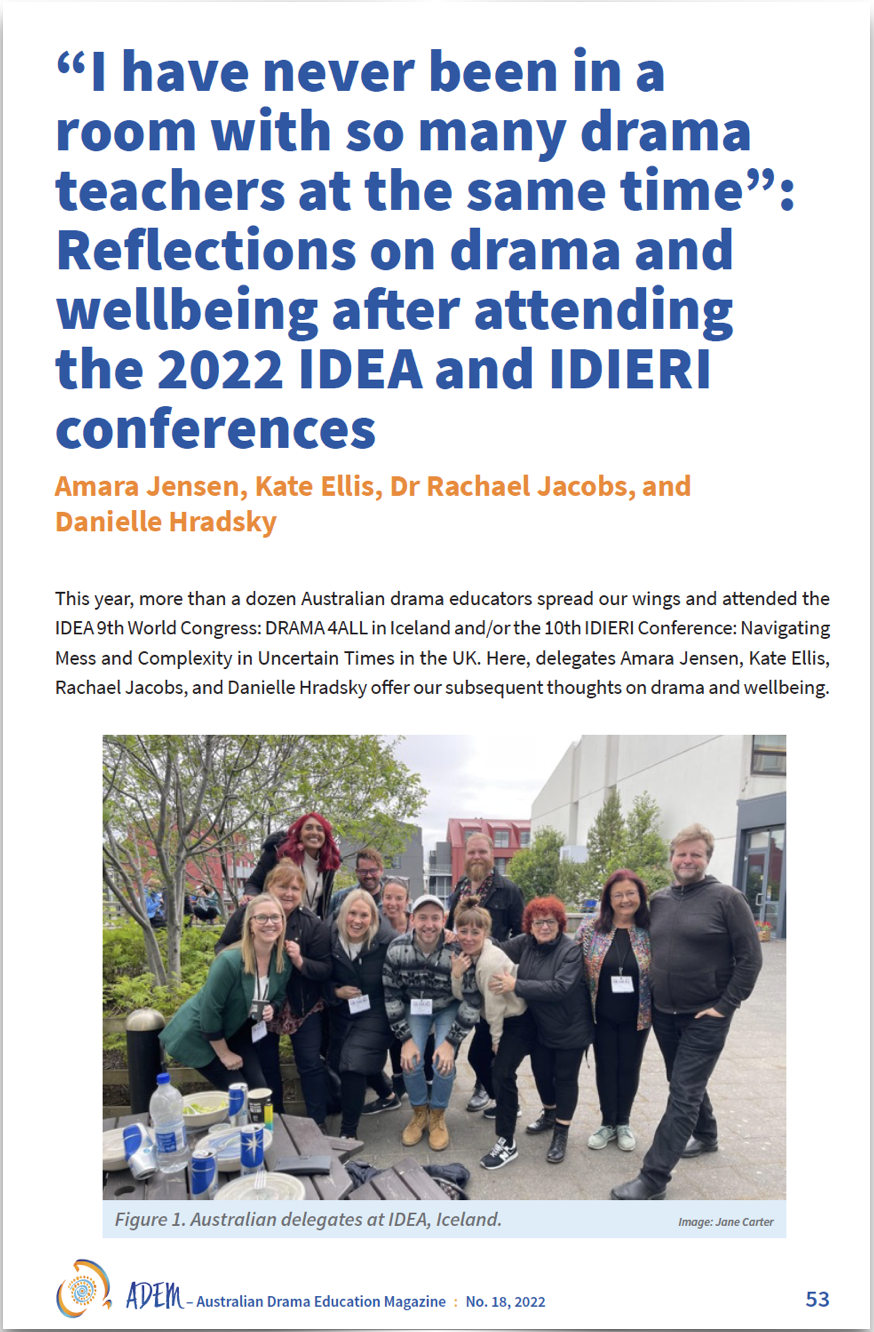

Drama Tuesday - Australian Drama Educators in the world

/Great to report that the latest edition of ADEM has been published including the image of the substantial number of Drama Australia participants. Encouraging to see in these COVID travel plagued times.

Other Drama Australia news

John Nicholas Saunders has handed the reins of Drama Australia Presidency to DR Jo Raphael.

Huge thanks to John for leading Drama Australia (and NAAE).

Welcome to Jo, a long time stalwart of Drama Australia.

Drama Australia journeys on showing leadership and strength.

Also included in ADEM is a summary from the report I made about IDEA2022 and published on StagePage www.stagepage.com.au

Drama Tuesday - Drama Australia Creating Community

/To subscribe to Drama Australia publications

Drama Australia AdministratorPO Box 1205, Milton, QLD 4064. AUSTRALIA

Ph: +61 7 3009 0664

Fax: +61 3009 0668

email: admin@dramaaustralia.org.au

It’s always exciting when Drama Australia publishes ADEM, the Australian Drama Education Magazine. ADEM sits alongside the fully referred NJ - Drama Australia Journal. It is designed to create community and share news.

This themed edition celebrates 10 years since the publication of Drama Australia’s Acting Green Guidelines (2011) – https://dramaaustralia.org.au/assets/files/Acting%20Green%20The%20case%20studies(1).pdf. ADEM calls for a timely revision and invites responses to a survey (https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/YQVK8G2) on ways of moving forward.

Drama Australia’s Acting Green guidelines were built on the understanding that sustainable drama and theatre practice and teaching about sustainability through drama are ways to directly involve students in understanding their connections with the natural environment, and the interdependence of systems that support life on Earth. They connect to the Australian Curriculum (ACARA)

The articles focused on Drama and Sustainability are a clear commitment to engaging with this key issue.

Eco-anxiety and Drama Education, Jo Raphael.

Unity in troubled times, Darcie Kane-Priestley, Emma McDonald, and Julia Prestia.

Two articles offer drama curriculum ideas based on children’s literature.

Susan Chapman writes about Drama giving voice to sustainability through an Arts immersion approach, exploring the novel Chelonia Green, Champion of Turtles (Mattingly, 2008).

Helen Sandercoe outlines a process drama based on ‘Circle’ by Jeannie Baker,

Learning about ecoscenography Tanja Beer.

Beyond the pandemic: Seeking sustainability in online drama education, Andrew Byrne, Susan Cooper, and Nick Waxman.

The final section provides 2021 Reflections from the State and Territory member Associations of Drama Australia.

In these times where the COVID-119 Pandemic has increased our sense of isolation, the value and need for a shared community of practice – as provided by Drama Australia and member associations – is essential and necessary.

Thank you Drama Australia for this latest initiative.

Thanks Dr Jo Raphael (Editor) and Danielle Hradsky (Associate Editor).

Drama Teacher Education – got my ticket for the long way round

/Drama Teacher Education in Australia is at crossroads.

For the Vision 2020 National Drama Conference due in Brisbane in April 2021, I re-worked my workshop presentation as a video and share it here.

The presentation draws on a chapter I have been writing and re-writing since 2020 for the Routledge Companion to Drama Education edited by Peter O’Connor and Mary McEvoy (forthcoming after a long delay caused by the Coronavirus COVID-19 Pandemic – another of the many pivots that have happened 2020-2021).

The text of the presentation is also included.

It is also published in the Digital library for the Conference that Drama Queensland has put together.

https://www.dramaqueensland.org.au/pd/conference/

Video Script

Drama Teacher Education – got my ticket for the long way round

Drama Teacher Education in Australia is at crossroads.

Robin Pascoe

Honorary Fellow, College of Science, Health, Engineering and Education (SHEE), Murdoch University, South Street, Murdoch, Western Australia 6150

Introduction

Drama Teacher Education in Australia is at another crossroads. Drama teacher education emerging within formal university structures in the mid 20th century until now has been a remarkable success story. But there is rapid and concerning change. Indicative of changes in other universities, 2019 was the last time that Drama Teacher Education Secondary was offered at Murdoch University. There are similar signs of contraction in other drama courses across Australian universities

Context: developing a drama teacher education course

I have spent the last 20 years teaching drama education beginning with asking colleagues fundamental questions:

What do you want teachers to know and be able to do on Day 1? And every day after that?

Over time I developed an approach based on the following principles:

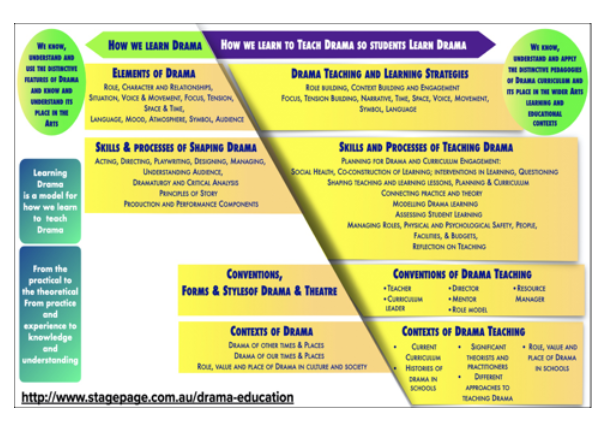

We learn to teach Drama in the way that we learn drama

To teach Drama effectively we develop two inter-related perspectives: how we learn Drama and how we teach so students learn Drama. They are connected ways of thinking, doing and being a drama teacher.

We learn Drama through experience, observation, modelling and being part of an ensemble. We learn to teach Drama through applying our direct experiences of drama and theatre; observing and modelling from others teaching drama; and, belonging to a community of shared practice (what I sometimes call a Guild of Drama Teachers).

In Learning Drama, we identify the distinctive nature of Drama/Theatre as an art form and its role in people’s lives, society and community. We learn Drama by making Drama recognising that it is hands-on, practical and experiential. It is embodied learning that brings together our body, mind and spirit. We understand that

Drama is aesthetic experience contextualised in the art forms’ histories, conventions and cultures.

In Learning to Teach Drama, we identify Drama as curriculum. We shape our practice in our Drama Teacher roles as teacher, curriculum leader, director, mentor, role model and resource manager.

Learning to teach Drama is practical, embodied experience. We learn to teach Drama by teaching Drama – by trying out strategies, concepts and approaches that help us refine our choice making as teachers.

In practice, this translated into an articulated course (Example available at http://www.stagepage.com.au/drama-education).

Conceptual learning was integrated into and followed practical experience. Hands on, practical examples of strategies, skills and processes were underpinned by connections with contexts, curriculum, theory, theorists and history. Key multiple roles of teaching drama – teacher, curriculum leader, director, mentor, role model and resource manager – were modelled and taught.

The current crisis

Drama teacher education in Australia began to be recognised in the 1960s. In Western Australia for example, in 1974 I was in the first intake of students permitted to take Drama Education as a major curriculum study at the Secondary Teachers College. The course outlined earlier was established in 2002 as the third available in Western Australia. As drama education grew in Western Australian schools (particularly with recognition of Drama ATAR in 1999) there has been a steady need for drama teachers. But there has been rapid and concerning change in the twenty-first century in the complex contemporary landscape of Australian universities.

In the past ten years or so there have been more than forty inquiries into different aspects of teacher education (Mills & Goos, November.13.2017). The Australian Government Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group (TEMAG) reported in Action Now: Classroom Ready Teachers (December 2014) issues and concerns. There is a populist tabloid perception that teacher education is flawed if not failing (see, for example, Shine, 2018). This, in turn, has led to intense politicised scrutiny and regulation including Accreditation of Initial Teacher Education Programs in Australia (AITSL, 2011) and the establishment of Australian Professional Standards for Teachers (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL), 2017). Yet, the situation is not clear cut.

Trends and patterns There has been an erosion of drama teacher education at my university over time and diffusion of focus in other Universities.

What is happening for drama teacher education is more than a response to the Coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic. There is a significant challenge to place of drama teacher education itself. To move beyond this moment, we need to better understand some deeper underlying issues.

Recognising the abyssal line

It is too easy to sound a warning about declining standards in drama teacher education. The tree that holds up the sky is uneasily still holding for us.

But as teacher educators in a contemporary world ,we have come to recognise “the abyssal line” (Santos, 2007), an invisible and unspoken line of presences and absences dividing worlds and world views into “us” and “them”. Things, people, ideas beyond that line are de-emphasised to the point that they are rendered null (in an Australian context, a terra nullius). This side of that line is what we collectively value, what we collectively think is important. In the eyes, minds and assumptions of many others both educators and the wider community, arts education is rendered as “other”, “peripheral”. Drama is negated, obscured, overlooked and rendered invisible, unimportant or non-essential (e.g., in course offerings in schools it is “optional”). When the dominant approaches to education consign arts education to this nether world, we have institutionalised “epistemicide” (Paraskeva, 2016) - a war on the knowledge(s) that we value, the destruction of existing knowledge and denial the possibilities of new knowledge(s).

To put it bluntly, what we believe in is not shared by many.

There continue to be many misconceptions about drama teaching.

Now more than ever we need as a drama education community to re-articulate our beliefs and values about drama education.

A robust schema for Drama Teacher Education

Whatever approach is taken to drama teacher education, there needs to be an underlying robust, durable, practical schema to serve as a living and responsive guide to our work.

Learning to teach drama focuses on embodied learning in the arts (Bresler, 2004). Through practical, hands on experiences in the drama we model the ways that your students learn the arts and ways that you teach the arts. This engenders embodied teaching.

This approach is based on sound research about providing:

analogue experiences – analogue experiences are like the ones students in drama experience; providing teachers with similar learning experiences that they need to facilitate for their students (Hilda Borko & Ralph T. Putnam, 1995; Morocco & Solomon, 1999)

content focus – unambiguous content description (Desimone, Porter, Garet, Yoon, & Birman, 2002; S.Garet, Porter, Desimone, Birman, & SukYoon, 2001; Shulman, 1986)

active learning – where teachers are engaged in the analysis of teaching and learning; learning from other teachers and from their own teaching; reviewing examples of effective teaching practice (Desimone et al., 2002; Franke, Carpenter, Fennema, Ansell, & Behrend, 1998; Franke, Fennema, & Carpenter, 1997; Morocco & Solomon, 1999; S.Garet et al., 2001)

dialogue amongst teachers – belonging to a community of drama teachers participating in discussion with practicing teachers (T. R. Guskey, 1986; T.R. Guskey, 2003; Virginia Richardson, October 1990)

long term support and feedback – support beyond the immediate experiences in the workshop through enrolling in community of drama teachers (H. Borko & R.T. Putnam, 1995; T.R. Guskey, 2002)

This is an articulated theoretical framework for drama teacher education course design that steps beyond pragmatic functionalism. It is a framework informed by Dewey, Vygotsky, Bruner, Eisner, Greene and others. Learning to teach drama involves acts of purposeful meaning making that draw together personal experiences and those of others (Dewey, 1938:2005; Eisner, 2002). No one learns alone – drama is intrinsically social learning (Grumet, 2004; Vygotsky, 1978). Drama teachers learn cognitively, somatically and affectively – mind, body and spirit (Peters, 2004). They work with enactive, iconic and symbolic modes (Bruner, 1990). Learning to teach drama engages aesthetic imagination (Greene, 1995). Learning to teach drama involves proactive participation in communities of practice (Wenger, 1998). Learning to teach drama organises drama knowledge, categorise it and uses strategies of paradigmatic thinking and narrative building (Bruner, 1991).

Every Drama Teacher needs a robust schema for what they are doing and why as the experienced drama teacher in the focus group articulated.

Peter Wright and I have written recently about Arts Teacher Education as Applied Aesthetic Understanding (in press) (adapted and extended from (Wetterstrand, 1999). Students need to:

see themselves as creators – as emerging artists beginning to develop understanding and control of specific skills and processes in drama

see themselves as thinking and engaging aesthetically. They critically engage with their own experiences and those of others

speak the language of the art form

display the habits of mind of artists and build cognitive and practical structures for managing their learning and teaching drama

build personal identity through drama and develop personal, social and cultural agency – capacity to initiate, manage and forge their own meaning making

develop perspective and a range of practical and informed understandings rather than take a simple unitary view of drama teaching

extend and deepen their understanding of the characteristics of drama as an art form and drama in the service of learning

reflect on their processes, products and their own learning in, through and about drama – and, beyond that, to human experience itself.

At the heart of it the developing drama teachers need capacity to cope with the sometimes stressful and always demanding work of teaching drama. They need to become reflective practitioners understanding and managing their multiple roles. All of which is underpinned by their practical knowledge, understanding of the skills and processes of the art form of Drama

An important point was made by an experienced teacher who was part of my initial focus group:

young teachers need to have an articulated philosophy of drama teaching. They must be clear about why they want to be a drama teacher. Their ultimate success as drama teachers relies significantly on their values about drama and about teaching. They needed a capacity built on respect, collaboration, working through process as well as product.

Conclusion

I don’t think I realised just how long the drama education journey would be when I entered that course in 1974. I got my ticket for the long way round.

There’s a song that’s an earworm in my life at the moment. I think its emblematic for a life in drama teacher education.

I got my ticket for the long way round

Two bottles of whiskey for the way

And I sure would like some sweet company

And I'm leaving tomorrow, what do you say

(Simone, 2013)

Drama teacher education and drama education itself, is a long-term project. There’s a need for a long view perspective. We are here for the long haul. Drama education and drama teacher education will survive the current road bumps. We will emerge a little shaken and stirred. But we must not lose sight of the long view and the challenges of helping those who make decisions to step over the abyssal line. Or that we as drama educators need in this time and into the future to walk both sides of that line.

The need for the robust schema outlined earlier is urgent and essential. Drama teacher education curriculum is not just content knowledge. It embodies ways of knowing and being in the world. It is too easy to play the misunderstood victim role as contexts change. It is necessary for us to strategically acknowledge and disarm critics and move past obstacles. It is insufficient to simply assert our place in the educational sun; we need to make the case with robust research based on experience that is not merely confirming the past but engaging future possibilities.

While I continue to work towards the long-term goals outlined, I know that this is not the task of one person and that at some point we all need to pass the baton to another generation. Long after I am gone, the case needs to be argued. We need to build drama teacher education as inevitable, as a self-evident truth.

References

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL). (2017). Australian Professional Standards for Teachers. Retrieved from https://www.aitsl.edu.au/teach/standards

Borko, H., & Putnam, R. T. (1995). Expanding a Teachers’ Knowledge Base: A Cognitive Psychological Perspective on Professional Development. In T. R. Guskey & M. Huberman (Eds.), Professional Development in Education: New Paradigms and Practices (pp. 35-66). New York: Teachers College Press.

Borko, H., & Putnam, R. T. (1995). Expanding a teacher’s knowledge base: A cognitive psychological perspective on professional development. In T. R. Guskey & M. Huberman (Eds.), Professional Development in Education. New York: New York: Teachers College Press.

Bresler, L. (2004). Knowing Bodies, Knowing Minds - Towards Embodied Teaching and Learning. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of Meaning. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bruner, J. (1991). The Narrative Construction of Reality. Critical Inquiry, 18(1), 1-21. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1343711

Desimone, L. M., Porter, A. C., Garet, M. S., Yoon, K. S., & Birman, B. F. (2002). Effects of Professional Development on Teachers' Instruction: Results from a Three-Year Longitudinal Study. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 24(2 (Summer 2002)), 81-112. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3594138

Dewey, J. (1938:2005). Art As Experience: Perigee Trade.

Eisner, E. W. (2002). What can eduction learn from the arts about the practice of education? John Dewey Lecture for 2002, Stanford University. Retrieved from www.infed.org/biblio/eisner_arts_and_the_practice_or_education.htm . Last updated: April 17, 2005.

Franke, M., Carpenter, T., Fennema, E., Ansell, E., & Behrend, J. (1998). Understanding teachers’ self- sustaining, generative change in the context of professional development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 14(1), 67-80.

Franke, M., Fennema, E., & Carpenter, T. (1997). Teachers creating change: Examining evolving beliefs and classroom practice. In E. Fennema & B. Scott-Nelson (Eds.), Mathematics teachers in transition (pp. 255-282). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Greene, M. (1995). Releasing the Imagination: Essays on Education, The Arts and Social Change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Grumet, M. (2004). No one learns alone. Putting the arts in the picture: Reframing education in the 21st century, 49-80.

Guskey, T. R. (1986). Staff development and the process of teacher change. Educational Researcher, 15, 5-12.

Guskey, T. R. (2002). Professional development and teacher change. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 8, 381-391.

Guskey, T. R. (2003). What makes professional development effective? Phi Delta Kappan, 84(10), 748-750.

Mills, M., & Goos, M. (November.13.2017). Three major concerns with teacher education reforms in Australia. Retrieved from https://www.aare.edu.au/blog/?p=2548

Morocco, C. C., & Solomon, M. Z. (1999). Revitalising professional development. In M. Z. Solomon (Ed.), The diagnostic teacher: Constructing new approaches to professional development (pp. 247-267). New York: Teachers College Press.

Paraskeva, J. (2016). Curriculum epistemicides. New York: Routledge.

Peters, M. (2004). Education and the Philosophy of the Body: Bodies of Knowledge and Knowledges of the Body. In L. Bresler (Ed.), Knowing Bodies, Moving Minds - Towards Embodied Teaching and Learning. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

S.Garet, M., Porter, A. C., Desimone, L., Birman, B. F., & SukYoon, K. (2001). What Makes Professional Development Effective? Results From a National Sample of Teachers. American Educational Research Journal. doi:https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312038004915

Santos, B. d. S. (2007). Beyond Abyssal Thinking: From Global Lines to Ecologies of Knowledges. Review, XXX(1).

Shine, K. (2018). Everything is negative’: Schoolteachers’ perceptions of news coverage of education. Journalism. Retrieved from https://espace.curtin.edu.au/bitstream/handle/20.500.11937/70003/267577.pdf

Shulman, L. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4-14.

Simone, J. (2013). Cups (You're Gonna Miss Me When I'm Gone). In.

Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group (TEMAG). (December 2014). Action Now: Classroom Ready Teachers. Retrieved from https://docs.education.gov.au/system/files/doc/otheraction_now_classroom_ready_teachers_print.pdf

Virginia Richardson. (October 1990). Significant and Worthwhile Change in Teaching Practice. Educational Researcher, 19(7), 10-18. doi:10.2307/1176411

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wetterstrand, G. (1999). Creating Understanding in Educational Drama. In C. Miller & J. Saxton (Eds.), Drama and Theatre in Education International Conversations. Victoria B.C.: American Educational Research Association Arts and Learning Special Interest Group and the International Drama in Education Research Institute July308 1997 Victoria, B.C. Canada.