Music Monday - How often do I need a music lesson?

/This year has marked a significant reduction in singing lessons at the tertiary institution I work for. Driven by budget constraints, the students are now provided with fortnightly lessons, where previously they were weekly. Furthermore, there are a number of non-teaching weeks in each semester (rehearsal, production and performance weeks) when classes are cancelled, so, in fact, the fortnight’s gap between lessons often becomes several weeks. In 2021 there are a total of 12 lessons per year in the 1st and 2nd years of the bachelor degree and 10 lessons in the 3rd year.

At the same time, in my other workplace, a specialist performing arts high school, there continue to be weekly lessons (40 per year). The irony has not been lost on me when sending home an email to the parents of a student who has missed a lesson – “only 8 more lessons this term – don’t miss any more!”

This strange 2021 dichotomy between my two teaching environments has set me thinking about how many lessons we actually need at the various stages of our training.

As a young child with a live-in piano teaching grandmother, I was used to the pupils turning up at their regular weekly lesson time. I guess the weekly lesson meant that each family’s household calendar was straightforward. Certainly in the beginning stages of learning any instrument (including the voice), regular lessons ensure that mistakes are not too practised in before correction by the teacher.

In my role as a high school voice teacher, I wear several hats – simultaneously I am teaching vocal technique, music literacy, interpretation skills, to name a few. The students need the weekly contact to maintain their growth and development.

In the tertiary environment, our 1st year students come from a variety of musical backgrounds. Because they are music theatre students, their individual skill levels vary. Some are strong dancers and inexperienced singers. Occasionally I have had a student with a prior degree in voice. The so-called triple threat encompasses singing, acting and dancing and no one starts the degree with equal skills in all three – I mean, why would they bother to do the course? It is very frustrating to be limited in how much instruction we can offer the beginners, who really need correction and guidance in the studio on a weekly basis.

If a reduction in practical training is to be a thing of the future, how can we fill the gaps?

Students could, of course, seek private teachers outside of the institution. The obvious benefit is the increased number of lessons. The potential downside is differing teacher approaches, which could be confusing in the early stages of training.

Technology offers some solutions. Although I am not a huge fan of the zoom music lesson – mainly because of the time lag involved – I do find that students benefit other uses of technology, such as submitting practice/ performance videos for teacher viewing and feedback. Is technology the way of the future here?

However, one thing that becomes clearer to me with every passing year is this – unless there is an investment in significant practice routines by the student, the number and frequency of lessons is irrelevant. A student who doesn’t practice will make as little progress with weekly, fortnightly, or even monthly lessons. But a student with good practice habits is going to progress faster with more regular instruction. Your thoughts?

Drama Tuesday - Against the odds

/A national drama education conference in plague times

In April 2020 the Drama Australia community were preparing to meet at the Vision 2020 National Conference to be held in Brisbane, Queensland. A little thing called the Coronavirus Pandemic intervened.

In April 2021 the same community were preparing to reconvene in Brisbane to have another go at this conference. This time it was a 3-day lockdown in Brisbane immediately before the conference was due to start. But the resilient Drama Australia community, led by Drama Queensland, pivoted to make this event an online event. A few lucky souls met in person at the QUT Conference venue but the rest of us were sitting at our computers - in my case two hours behind Brisbane (which was a strange and unnerving experience).

It is important to reflect both on the resilience of the community as well as the themes that emerged in this particular conference.

The focus on recognition of indigenous and aboriginal voices is is noticeable. In particular (though not alone in a wide program) was ‘You Can’t Be What You Can’t See’ – Representation, Diversity and being a Brown Kid in Toowoomba

by Ari Palani, La Boite Theatre. Delivered from the heart with authenticity, this keynote set a thoughtful and yet provocative tone for the conference as a whole.

Many presentations were recorded and will be available through the Drama Queensland portal.

They are published published in the Digital library for the Conference that Drama Queensland has put together. https://www.dramaqueensland.org.au/pd/conference/

Another of the important pieces of information embedded in the Conference was a presentation from ACARA The Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. A heads up for the Drama Australia community – and the whole Arts Education community, ACARA has announced a review of the Australian Curriculum :The Arts (as part of a curriculum wide review).

Information about the Review can be found at https://acara.edu.au/curriculum/curriculum-review

The Review will be carried out concurrently in all eight learning areas. The review will give a particular focus to the F–6 curriculum in order to reduce overcrowding and provide improved manageability and coherence to the curriculum for the primary years of schooling. The scale and magnitude of content refinement and reduction will not be the same across all learning areas.

There are some good news stories for Arts educators – For example

Learning in and through The Arts enables and promotes transferable knowledge, skills and dispositions seen as essential for

today’s world, 2030 and beyond.

“The potential of the arts in symphony to promote self-understanding and wellbeing and to make meaning to illuminate the advantages of viewing the world from multiple perspectives is limitless. Contemporary research, alongside multi-disciplinary and transdisciplinary arts-rich initiatives, underline that we must blur the boundaries while maintaining respect for the integrity of each arts discipline.” (Ewing, R, in More than words can say, A view of literacy through the Arts, ed. Dyson, J, NAAE, 2019)

But we should be aware of the timeline.

People interested can contact ACARA – helen.champion@acara.edu.au

Music Monday - Which layer of the music do you hear best?

/A couple of weeks ago I attended a singing concert given by our graduating class of acting students. It is a class that I have taught for the past 25 years, and passed up this year as the start of a general reducing of my teaching hours.

For past concerts I have been the accompanist and this time I was in the audience enjoying the whole experience. A couple of observations surprised me. For a start, I found that my attention kept straying to the pianist – despite compelling story-telling from the singers concerned. Was part of me wishing I was still on the piano stool? Or was it the fact that the accompanist is one of our finest local pianists? Or something else?

One of the challenges in training classes of acting students to sing is that there is a wide range of natural ability, experience and inclination present. This group were all strong at the story-telling aspect of singing, a couple had pitch issues and several are all round strong singers. With the last category, I was more able to appreciate the whole tapestry of their song – text on melody and the harmonic layers of the accompaniment.

In the week which followed, I was in one of my secondary school singing classes, but for once the students were silent. They were completing a written ‘marking up the score’ task in preparation for some sight-singing. In nearby rooms the faint sounds of clarinet and violin lessons could be heard. One of the students commented on how distracting the sounds were. Another said that she always likes to hear the background lessons when we are quiet in our singing class. Someone else noticed that the violin and clarinet clashed with each other but yet another student remarked that she thought it sounded like a really interesting piece of (unintentional) music. At this point a student, who had been intensely focussed on figuring out the solfa for the sight-singing piece, looked up and asked, “What are you talking about? I don’t hear anything.”

We can never really know what audiences hear when they listen to music. For example, that wonderful, evocative wash of sound in so many piano concerti of the Romantic period is created by the harmonic structure. We hum the tunes, but we inwardly hear the harmonies from both piano and orchestra.

How can we submit to the complete tapestry of music without our own preferences (and prejudices?) distracting?

Is it easier for audiences without music training to appreciate the whole concert experience?

These are my current preoccupying thoughts.

Drama Teacher Education – got my ticket for the long way round

/Drama Teacher Education in Australia is at crossroads.

For the Vision 2020 National Drama Conference due in Brisbane in April 2021, I re-worked my workshop presentation as a video and share it here.

The presentation draws on a chapter I have been writing and re-writing since 2020 for the Routledge Companion to Drama Education edited by Peter O’Connor and Mary McEvoy (forthcoming after a long delay caused by the Coronavirus COVID-19 Pandemic – another of the many pivots that have happened 2020-2021).

The text of the presentation is also included.

It is also published in the Digital library for the Conference that Drama Queensland has put together.

https://www.dramaqueensland.org.au/pd/conference/

Video Script

Drama Teacher Education – got my ticket for the long way round

Drama Teacher Education in Australia is at crossroads.

Robin Pascoe

Honorary Fellow, College of Science, Health, Engineering and Education (SHEE), Murdoch University, South Street, Murdoch, Western Australia 6150

Introduction

Drama Teacher Education in Australia is at another crossroads. Drama teacher education emerging within formal university structures in the mid 20th century until now has been a remarkable success story. But there is rapid and concerning change. Indicative of changes in other universities, 2019 was the last time that Drama Teacher Education Secondary was offered at Murdoch University. There are similar signs of contraction in other drama courses across Australian universities

Context: developing a drama teacher education course

I have spent the last 20 years teaching drama education beginning with asking colleagues fundamental questions:

What do you want teachers to know and be able to do on Day 1? And every day after that?

Over time I developed an approach based on the following principles:

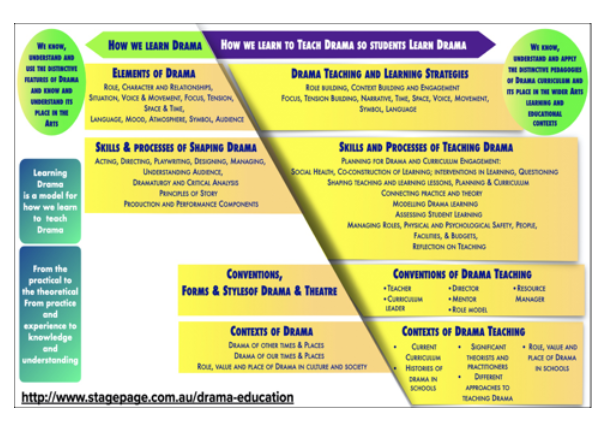

We learn to teach Drama in the way that we learn drama

To teach Drama effectively we develop two inter-related perspectives: how we learn Drama and how we teach so students learn Drama. They are connected ways of thinking, doing and being a drama teacher.

We learn Drama through experience, observation, modelling and being part of an ensemble. We learn to teach Drama through applying our direct experiences of drama and theatre; observing and modelling from others teaching drama; and, belonging to a community of shared practice (what I sometimes call a Guild of Drama Teachers).

In Learning Drama, we identify the distinctive nature of Drama/Theatre as an art form and its role in people’s lives, society and community. We learn Drama by making Drama recognising that it is hands-on, practical and experiential. It is embodied learning that brings together our body, mind and spirit. We understand that

Drama is aesthetic experience contextualised in the art forms’ histories, conventions and cultures.

In Learning to Teach Drama, we identify Drama as curriculum. We shape our practice in our Drama Teacher roles as teacher, curriculum leader, director, mentor, role model and resource manager.

Learning to teach Drama is practical, embodied experience. We learn to teach Drama by teaching Drama – by trying out strategies, concepts and approaches that help us refine our choice making as teachers.

In practice, this translated into an articulated course (Example available at http://www.stagepage.com.au/drama-education).

Conceptual learning was integrated into and followed practical experience. Hands on, practical examples of strategies, skills and processes were underpinned by connections with contexts, curriculum, theory, theorists and history. Key multiple roles of teaching drama – teacher, curriculum leader, director, mentor, role model and resource manager – were modelled and taught.

The current crisis

Drama teacher education in Australia began to be recognised in the 1960s. In Western Australia for example, in 1974 I was in the first intake of students permitted to take Drama Education as a major curriculum study at the Secondary Teachers College. The course outlined earlier was established in 2002 as the third available in Western Australia. As drama education grew in Western Australian schools (particularly with recognition of Drama ATAR in 1999) there has been a steady need for drama teachers. But there has been rapid and concerning change in the twenty-first century in the complex contemporary landscape of Australian universities.

In the past ten years or so there have been more than forty inquiries into different aspects of teacher education (Mills & Goos, November.13.2017). The Australian Government Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group (TEMAG) reported in Action Now: Classroom Ready Teachers (December 2014) issues and concerns. There is a populist tabloid perception that teacher education is flawed if not failing (see, for example, Shine, 2018). This, in turn, has led to intense politicised scrutiny and regulation including Accreditation of Initial Teacher Education Programs in Australia (AITSL, 2011) and the establishment of Australian Professional Standards for Teachers (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL), 2017). Yet, the situation is not clear cut.

Trends and patterns There has been an erosion of drama teacher education at my university over time and diffusion of focus in other Universities.

What is happening for drama teacher education is more than a response to the Coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic. There is a significant challenge to place of drama teacher education itself. To move beyond this moment, we need to better understand some deeper underlying issues.

Recognising the abyssal line

It is too easy to sound a warning about declining standards in drama teacher education. The tree that holds up the sky is uneasily still holding for us.

But as teacher educators in a contemporary world ,we have come to recognise “the abyssal line” (Santos, 2007), an invisible and unspoken line of presences and absences dividing worlds and world views into “us” and “them”. Things, people, ideas beyond that line are de-emphasised to the point that they are rendered null (in an Australian context, a terra nullius). This side of that line is what we collectively value, what we collectively think is important. In the eyes, minds and assumptions of many others both educators and the wider community, arts education is rendered as “other”, “peripheral”. Drama is negated, obscured, overlooked and rendered invisible, unimportant or non-essential (e.g., in course offerings in schools it is “optional”). When the dominant approaches to education consign arts education to this nether world, we have institutionalised “epistemicide” (Paraskeva, 2016) - a war on the knowledge(s) that we value, the destruction of existing knowledge and denial the possibilities of new knowledge(s).

To put it bluntly, what we believe in is not shared by many.

There continue to be many misconceptions about drama teaching.

Now more than ever we need as a drama education community to re-articulate our beliefs and values about drama education.

A robust schema for Drama Teacher Education

Whatever approach is taken to drama teacher education, there needs to be an underlying robust, durable, practical schema to serve as a living and responsive guide to our work.

Learning to teach drama focuses on embodied learning in the arts (Bresler, 2004). Through practical, hands on experiences in the drama we model the ways that your students learn the arts and ways that you teach the arts. This engenders embodied teaching.

This approach is based on sound research about providing:

analogue experiences – analogue experiences are like the ones students in drama experience; providing teachers with similar learning experiences that they need to facilitate for their students (Hilda Borko & Ralph T. Putnam, 1995; Morocco & Solomon, 1999)

content focus – unambiguous content description (Desimone, Porter, Garet, Yoon, & Birman, 2002; S.Garet, Porter, Desimone, Birman, & SukYoon, 2001; Shulman, 1986)

active learning – where teachers are engaged in the analysis of teaching and learning; learning from other teachers and from their own teaching; reviewing examples of effective teaching practice (Desimone et al., 2002; Franke, Carpenter, Fennema, Ansell, & Behrend, 1998; Franke, Fennema, & Carpenter, 1997; Morocco & Solomon, 1999; S.Garet et al., 2001)

dialogue amongst teachers – belonging to a community of drama teachers participating in discussion with practicing teachers (T. R. Guskey, 1986; T.R. Guskey, 2003; Virginia Richardson, October 1990)

long term support and feedback – support beyond the immediate experiences in the workshop through enrolling in community of drama teachers (H. Borko & R.T. Putnam, 1995; T.R. Guskey, 2002)

This is an articulated theoretical framework for drama teacher education course design that steps beyond pragmatic functionalism. It is a framework informed by Dewey, Vygotsky, Bruner, Eisner, Greene and others. Learning to teach drama involves acts of purposeful meaning making that draw together personal experiences and those of others (Dewey, 1938:2005; Eisner, 2002). No one learns alone – drama is intrinsically social learning (Grumet, 2004; Vygotsky, 1978). Drama teachers learn cognitively, somatically and affectively – mind, body and spirit (Peters, 2004). They work with enactive, iconic and symbolic modes (Bruner, 1990). Learning to teach drama engages aesthetic imagination (Greene, 1995). Learning to teach drama involves proactive participation in communities of practice (Wenger, 1998). Learning to teach drama organises drama knowledge, categorise it and uses strategies of paradigmatic thinking and narrative building (Bruner, 1991).

Every Drama Teacher needs a robust schema for what they are doing and why as the experienced drama teacher in the focus group articulated.

Peter Wright and I have written recently about Arts Teacher Education as Applied Aesthetic Understanding (in press) (adapted and extended from (Wetterstrand, 1999). Students need to:

see themselves as creators – as emerging artists beginning to develop understanding and control of specific skills and processes in drama

see themselves as thinking and engaging aesthetically. They critically engage with their own experiences and those of others

speak the language of the art form

display the habits of mind of artists and build cognitive and practical structures for managing their learning and teaching drama

build personal identity through drama and develop personal, social and cultural agency – capacity to initiate, manage and forge their own meaning making

develop perspective and a range of practical and informed understandings rather than take a simple unitary view of drama teaching

extend and deepen their understanding of the characteristics of drama as an art form and drama in the service of learning

reflect on their processes, products and their own learning in, through and about drama – and, beyond that, to human experience itself.

At the heart of it the developing drama teachers need capacity to cope with the sometimes stressful and always demanding work of teaching drama. They need to become reflective practitioners understanding and managing their multiple roles. All of which is underpinned by their practical knowledge, understanding of the skills and processes of the art form of Drama

An important point was made by an experienced teacher who was part of my initial focus group:

young teachers need to have an articulated philosophy of drama teaching. They must be clear about why they want to be a drama teacher. Their ultimate success as drama teachers relies significantly on their values about drama and about teaching. They needed a capacity built on respect, collaboration, working through process as well as product.

Conclusion

I don’t think I realised just how long the drama education journey would be when I entered that course in 1974. I got my ticket for the long way round.

There’s a song that’s an earworm in my life at the moment. I think its emblematic for a life in drama teacher education.

I got my ticket for the long way round

Two bottles of whiskey for the way

And I sure would like some sweet company

And I'm leaving tomorrow, what do you say

(Simone, 2013)

Drama teacher education and drama education itself, is a long-term project. There’s a need for a long view perspective. We are here for the long haul. Drama education and drama teacher education will survive the current road bumps. We will emerge a little shaken and stirred. But we must not lose sight of the long view and the challenges of helping those who make decisions to step over the abyssal line. Or that we as drama educators need in this time and into the future to walk both sides of that line.

The need for the robust schema outlined earlier is urgent and essential. Drama teacher education curriculum is not just content knowledge. It embodies ways of knowing and being in the world. It is too easy to play the misunderstood victim role as contexts change. It is necessary for us to strategically acknowledge and disarm critics and move past obstacles. It is insufficient to simply assert our place in the educational sun; we need to make the case with robust research based on experience that is not merely confirming the past but engaging future possibilities.

While I continue to work towards the long-term goals outlined, I know that this is not the task of one person and that at some point we all need to pass the baton to another generation. Long after I am gone, the case needs to be argued. We need to build drama teacher education as inevitable, as a self-evident truth.

References

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL). (2017). Australian Professional Standards for Teachers. Retrieved from https://www.aitsl.edu.au/teach/standards

Borko, H., & Putnam, R. T. (1995). Expanding a Teachers’ Knowledge Base: A Cognitive Psychological Perspective on Professional Development. In T. R. Guskey & M. Huberman (Eds.), Professional Development in Education: New Paradigms and Practices (pp. 35-66). New York: Teachers College Press.

Borko, H., & Putnam, R. T. (1995). Expanding a teacher’s knowledge base: A cognitive psychological perspective on professional development. In T. R. Guskey & M. Huberman (Eds.), Professional Development in Education. New York: New York: Teachers College Press.

Bresler, L. (2004). Knowing Bodies, Knowing Minds - Towards Embodied Teaching and Learning. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of Meaning. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bruner, J. (1991). The Narrative Construction of Reality. Critical Inquiry, 18(1), 1-21. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1343711

Desimone, L. M., Porter, A. C., Garet, M. S., Yoon, K. S., & Birman, B. F. (2002). Effects of Professional Development on Teachers' Instruction: Results from a Three-Year Longitudinal Study. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 24(2 (Summer 2002)), 81-112. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3594138

Dewey, J. (1938:2005). Art As Experience: Perigee Trade.

Eisner, E. W. (2002). What can eduction learn from the arts about the practice of education? John Dewey Lecture for 2002, Stanford University. Retrieved from www.infed.org/biblio/eisner_arts_and_the_practice_or_education.htm . Last updated: April 17, 2005.

Franke, M., Carpenter, T., Fennema, E., Ansell, E., & Behrend, J. (1998). Understanding teachers’ self- sustaining, generative change in the context of professional development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 14(1), 67-80.

Franke, M., Fennema, E., & Carpenter, T. (1997). Teachers creating change: Examining evolving beliefs and classroom practice. In E. Fennema & B. Scott-Nelson (Eds.), Mathematics teachers in transition (pp. 255-282). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Greene, M. (1995). Releasing the Imagination: Essays on Education, The Arts and Social Change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Grumet, M. (2004). No one learns alone. Putting the arts in the picture: Reframing education in the 21st century, 49-80.

Guskey, T. R. (1986). Staff development and the process of teacher change. Educational Researcher, 15, 5-12.

Guskey, T. R. (2002). Professional development and teacher change. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 8, 381-391.

Guskey, T. R. (2003). What makes professional development effective? Phi Delta Kappan, 84(10), 748-750.

Mills, M., & Goos, M. (November.13.2017). Three major concerns with teacher education reforms in Australia. Retrieved from https://www.aare.edu.au/blog/?p=2548

Morocco, C. C., & Solomon, M. Z. (1999). Revitalising professional development. In M. Z. Solomon (Ed.), The diagnostic teacher: Constructing new approaches to professional development (pp. 247-267). New York: Teachers College Press.

Paraskeva, J. (2016). Curriculum epistemicides. New York: Routledge.

Peters, M. (2004). Education and the Philosophy of the Body: Bodies of Knowledge and Knowledges of the Body. In L. Bresler (Ed.), Knowing Bodies, Moving Minds - Towards Embodied Teaching and Learning. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

S.Garet, M., Porter, A. C., Desimone, L., Birman, B. F., & SukYoon, K. (2001). What Makes Professional Development Effective? Results From a National Sample of Teachers. American Educational Research Journal. doi:https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312038004915

Santos, B. d. S. (2007). Beyond Abyssal Thinking: From Global Lines to Ecologies of Knowledges. Review, XXX(1).

Shine, K. (2018). Everything is negative’: Schoolteachers’ perceptions of news coverage of education. Journalism. Retrieved from https://espace.curtin.edu.au/bitstream/handle/20.500.11937/70003/267577.pdf

Shulman, L. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4-14.

Simone, J. (2013). Cups (You're Gonna Miss Me When I'm Gone). In.

Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group (TEMAG). (December 2014). Action Now: Classroom Ready Teachers. Retrieved from https://docs.education.gov.au/system/files/doc/otheraction_now_classroom_ready_teachers_print.pdf

Virginia Richardson. (October 1990). Significant and Worthwhile Change in Teaching Practice. Educational Researcher, 19(7), 10-18. doi:10.2307/1176411

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wetterstrand, G. (1999). Creating Understanding in Educational Drama. In C. Miller & J. Saxton (Eds.), Drama and Theatre in Education International Conversations. Victoria B.C.: American Educational Research Association Arts and Learning Special Interest Group and the International Drama in Education Research Institute July308 1997 Victoria, B.C. Canada.

Foreman Funnies - Who Knows! Cyranose!

/“A great nose may be an index/ Of a great soul”

― Edmond Rostand, Cyrano de Bergerac

Ah, the joys of double casting.

Every Drama teacher’s nightmare.

Double the cast, quadruple the work.

That’s what Robin and I did for our ’86 adaptation of Cyrano.

Oh yes, and all written in blank verse.

Strangely enough after a while I found myself thinking in blank verse.

Cyrano’s nose

Of course, we had two Cyranos. And two very different noses to find/make; one very solid chunk of a Roman nose and one much finer, Nordic nose.

I’d been having fun using plaster of Paris bandage for mask making so I thought, Easy. I made a cast of each one, then filled each clay. Wait for it to dry, peel away the plaster, build up each with plasticine. But then what. I’d been making the masks by layering onto a positive mould. That wouldn’t work for this.

I sourced some cold moulding latex. And had to make another mould of each new nose. And then remove the plasticine. I had never used latex before but lucked out that the first pour worked, and the resultant noses fitted but needed paint and make-up.

Job done. Well, that job done.

Then there was the fight. At the end of Act One. Involving 15 people.

I’ve since explained to classes that a stage fight is very much a choreographed free dance. Every action and reaction must be carefully planned if it is to be performed over a number of shows. And safely. Each combatant MUST know exactly they are doing and when and where. Relatively easy when it is two people. Toss in the cross interaction between three, six, twelve, fifteen cast members on stage…

Now for cast two!

I swear we spent hours on three minutes of stage time. That three minutes was problematic, too. As the cast worked and re-worked the fight everything sped up. They knew what they were doing. [The cast of Starlight Express – performed on roller blades – cut the running time of performances by fifteen minutes the further into the run they went.]

Not forgetting… the car on stage (It was after all a ‘Modern’ version)

Oh yeah, and a car on stage. An old Cortina was donated – too long to fit on stage! So, the ‘Shed Men” cat school ut off the roof and cut out the back seat, then welded both halves of our now convertible back together. Painted pink with white-walled tyres, a ‘foxtail’ on the aerial and headlights connected to a battery, it was ready.

There was no room backstage for it so it stayed onstage, under a black sheet for the first two scenes. Blackout. Sheet removed, rolled forward three meters, lights up… and gasps from the audience. They truly had not noticed it sitting there.

Drama Tuesday - A Cyrano for the Times

/“Take it, and turn to facts my fantasies.”

― Edmond Rostand, Cyrano de Bergerac

An antipodean and retro Cyrano with high school kids

Armadale SHS Production 1986

Airing on SBS this week is a delightful recent French comedy film Cyrano My Love (In French released as Edmond).

A fanciful tale of Edmond Rostand “writing” Cyrano in a madcap few days with inspiration gleaned from his actor friend’s love for a costumier; a over the hill actor desperate for a leading role; a chaotic and comedic backstage account of the writing and staging of the play before going on to be a significant success with over 20,000 productions in the 20th Century alone.

You can take the “historical accuracy” with the pre-requisite pinch of salt. But it doesn’t make it any the less funny. The scene where Edmond improvises (in verse) the famous “nose speech, drawing images and metaphors out of thin air in a backstage walk is delightfully inventive. If you are in anyway familiar with the play (or its many adaptations like the limp Roxanne with Steve Martin) then there are resonances to be milked.

This was a play that celebrated the very theatricality of theatre – the long tradition of the playing within the play.

But having watched it (when I probably should have been tucked up in bed) I was transported to the production that John Foreman and I did at Armadale Senior High in 1986.

Who on earth would have thought that it was a good idea to tackle this High Romance from the French Belle Epoch? People must have thought that we had rocks in our head to even contemplate it. But we did it.

More than that we had the reckless and rash notion of re-shaping the play into a 1960’s setting! And that we would intersperse rock songs throughout (to move the whole 5 act structure along at a cracking pace).

It was an act of hubris (of the kind that drama teachers are so fond of).

But… it did work.

And the students did respond to the text and built their own connections.

The closing scene with the mortally wounded Cyrano finally revealing his true love for Roxanne was introduced by the melancholy of the Don McLean song American Pie

Something touched me deep inside

The day the music died

Not surprisingly, I am fascinated by these plays about plays.

I return (as a teacher) to sharing Stage Beauty about the transition point in Restoration Theatre when women were able to take roles on stage. (Directed by Richard Eyre. The screenplay by Jeffrey Hatcher is based on his play Compleat Female Stage Beauty, which was inspired by references to 17th-century actor Edward Kynaston made in the detailed private diary kept by Samuel Pepys.

Of course, there is Shakespeare in Love with all of Tom Stoppard’s wit.

“- Philip Henslowe: Mr. Fennyman, allow me to explain about the theatre business. The natural condition is one of insurmountable obstacles on the road to imminent disaster.

- Hugh Fennyman: So what do we do?

- Philip Henslowe: Nothing. Strangely enough, it all turns out well.

- Hugh Fennyman: How?

- Philip Henslowe: I don't know. It's a mystery.”

“Cyrano, My Love,” was written and directed by Alexis Michalik, adapting his own acclaimed play,

Like any high school production there were rough edges and some bumpier performances, but what this production did was to open the doors to a kind of theatre that was not harsh realism or Brechtian alienation. It opened minds to theatre seen through the lenses of time and continuity. It opened hearts to how music swells dramatic action.

It’s a long time since that production – and those actors are now out there in the world with fading memories. The disintegrating paper scripts sit on my shelves slowing dissolving into dust (and who knows where the disc is – or if there is any technology that can possibly read it). But I wanted to remind us as drama teachers that sometimes we need to take bold and huge risks and to step out into the vast planes of imagined possibilities. Too often now I see drama in schools shuttering down; what will maximise the ATAR score thinking. It’s not easy to be bold. It’s risky business to push the boundaries. When it works, it’s worth it.

The first page of the script evokes the vaulting ambition of our production.

Now all I have to do is find the images from the production.

Music Monday - Adrian Adam Maydwell Music Archive

/AAMMA.CO

Perth based harpist, choral director, musicologist and collector and researcher of all choral things Renaissance, Baroque and Bolivian, Anthony (Tony) Maywell, has set up a collection of works in memory of his son Adrian, also a musician and singer, who tragically lost his life in a road accident.

There are over 170 works already uploaded and eventually there will be over a thousand.

All are available for free with the only proviso being that appropriate attribution is given in performance.

This is an incredible gesture from Anthony Maydwell and one which will benefit generations of musicians who love to play and sing this music. Tony writes in a facebook post:

Adrian loved this repertoire and had opportunity to sing a great deal of it during his lifetime. Faith and I hope this will in a small way keep his memory alive for those who knew him and further an appreciation for the rich experience that can be had from singing and listening to this beautiful music.

Please share details of the site with musician friends.

Drama Tuesday - Why Drama – preparing young people for uncertain futures

/For the past few years I have been working with drama educators in China through keynotes and workshops. IDEC one of the IDEA members located in Beijing has been a wonderful collaborator on the development of interest and enthusiasm for drama teaching. There has been remarkable growth in the field. In May 2021, IDEC are staging another conference (though, of course, limited in the Coronavirus Pandemic). They asked me to talk about ho drama prepares young people for uncertain futures.

It is useful to go back to our fundamental understandings to remind ourselves of the reasons why we teach drama.

I share with you the recording I have just finished. Text is included below.

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

The Coronavirus COVID-19 Pandemic has taught us many lessons. One of the most important is being prepared for uncertain futures. We have learnt the importance of the need to respond quickly as circumstances change. Drama teaches us about responding. Drama teaches us about improvising without pre-written scripts. Drama teaches us to focus on what it is to be human in the world.

When our students have authentic opportunities to work with the Elements of Drama, they develop their skills of enacting role and relationships, telling stories creating dramatic action and situations. They understand how tension drives dramatic action using space, and time, voice and movement and symbols, language, mood and atmosphere. The drama they learn and create and respond to develops an awareness of their world and enables them to imagine their futures.

Drama education provides opportunities for observing and understanding people – including themselves. Through playing these roles and exploring relationships, they understand what it is to be human. This is developing personal identity. This is a key skill for understanding and engaging with our collective uncertain futures.

Drama education provides opportunities for trying out possibilities and exploring alternatives. In drama we can stop the action and restart it differently. We can stop the drama and reflect on what happened and what could happen next. Drama gives the chance of playing and replaying action. We can test our futures.

Drama education provides opportunities for entering the world that we live in and exploring it. These everyday stories about ordinary experiences help us understand our sense of personal, social and cultural identity.

Drama education provides opportunities for exploring the choices that we make in life – the ethical choices and the values that we need for a successful future. In learning to express and communicate ideas and feelings through stories enacted for others, our students learn to make choices and learning about becoming good people – people who care for others, show compassion and empathy and understanding.

Drama education provides opportunities for understanding and sharing emotions. Learning to express themselves and their feelings, helps prepare for a world where it is important to show who we are to the world with honesty and authenticity.

Drama education provides opportunities for sharing the stories of the past – the ones that have been handed to us over generations. And to understand them for the future as we hand them to our future children.

Drama education provides opportunities for creativity and play. whatever unfolds in the future, there will continue to be the need for creativity and play. Creativity to imagine and re-imagine possibilities. Play as a context for learning.

Drama education provides opportunities for learning together and building teams collaborating

To summarise some of the big ideas of this presentation, drama gives us opportunities to rehearse the past and present for the future.

There has been a long history of “future thinking” – thinking about the skills needed for the future.

Writing in 2018 before the Pandemic, Stowe Boyd identified 10 Work Skills for An Uncertain Future.

I share some of this this work with you to make the point that Drama education can and does develop these skills.

To this list we can add that drama helps us respond to the uncertain futures through developing our skills in:

responding to people, relationships and situations - drama is action and response

problem solving – Drama is active problem solving

working together collaboratively for shared goals – Drama is team work

creative and critical thinking – Through Drama we ask questions and work creatively

We are not alone in seeking to re-imagine the world of learning for uncertain futures. As we meet in 2021, UNESCO is in the midst of project of magnitude that we should pay attention to. And we need to remind the decision makers and policy makers of the role of drama in educating for the future.

The playwright Shakespeare had Hamlet provide famous advice to players in hamlet prince of Denmark. There is good advice there for us to share with our students – don’t weave your arms around too much; don’t shout your lines; Suit the action to the word, the word to the action. And at the heart of drama education is his advice

“the purpose of playing, whose end, both at the first and now, was and is, to hold, as 'twere, the mirror up to nature”.

We don’t know what the future will bring – some things good, some things uncertain. But we will always have drama as a powerful way of holding the mirror up to what we see.

Thank you for the opportunity to talk with you today.

I am a proud advocate for the power of drama to enrich and enhance the lives of young people.I encourage you to be the voice and action of drama education in your world. It changes the lives of all who participate.

You can find more of my thoughts and ideas at www.stagepage.com.au

and through IDEA www.ideadrama.org

Thank you for listening.

Bibliography

Boyd, R. N. (1988). How to Be a Moral Realist. In G. Sayre-McCord (Ed.), Essays on Moral Realism (pp. 181-128). New York: Cornell University Press.

Music Monday - Composing music at age 70.

/This weekend our family celebrated a milestone for Robin Pascoe – he turned 70. In many ways it is hard to believe – he is still teaching and writing (words, not music) at the same energetic pace.

But the calendar does not lie, and the mirror also gives the occasional brutal clue as well!

As we reminisced over his three score years plus ten, I found myself thinking of my favourite composers. Sadly, many did not make 70; however, I did find four favourites who published works at 70 or above.

Stephen Sondheim (1930-) Bounce written in 2003, later retitled Roadshow in 2008.

Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992) Saint-Francois d’Assise, Opera in 3 acts, written between 1975-83.

Aaron Copland (1900-1990) Wrote Night Thoughts in 1972 for the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition

Richard Rodgers (1902-1979) Two By Two (1970), Rex (1976), I Remember Mama (1979)

Can you add to this list? Please do so in the comments section below.