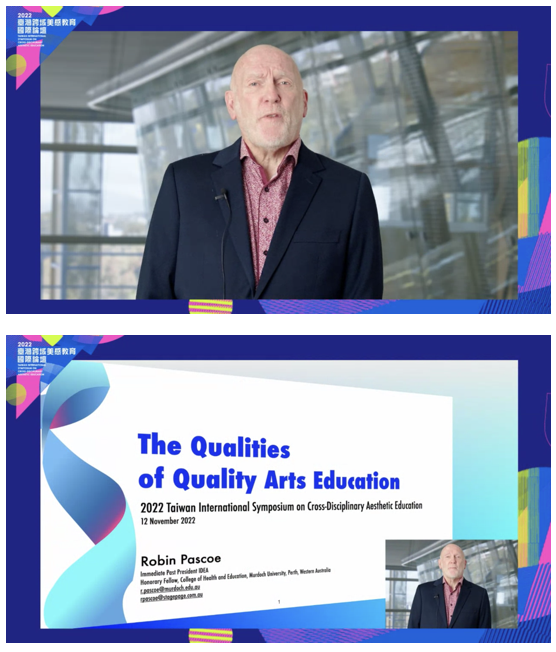

Drama Tuesday - Do you remember your first drama lesson?

/Critical Incident Methodologies for Future Practice

Robin Pascoe,

Honorary Fellow, School of Health and Education, Murdoch University. Immediate Past President IDEA

I don’t pose that question as an exercise in nostalgia. This is a serious question designed to stimulate reflective practice. Our first experience is drama teachers often shape us and leave indelible marks. Before you read on, take time to reflect on your first drama teaching experiences. What do you remember? What was positive? What do you back on perhaps with a smile or a cringe about your “mistakes”?

For me, my first drama teaching was in a different century, and we all know that the past is a different country, and they do things differently there.

Things were different then

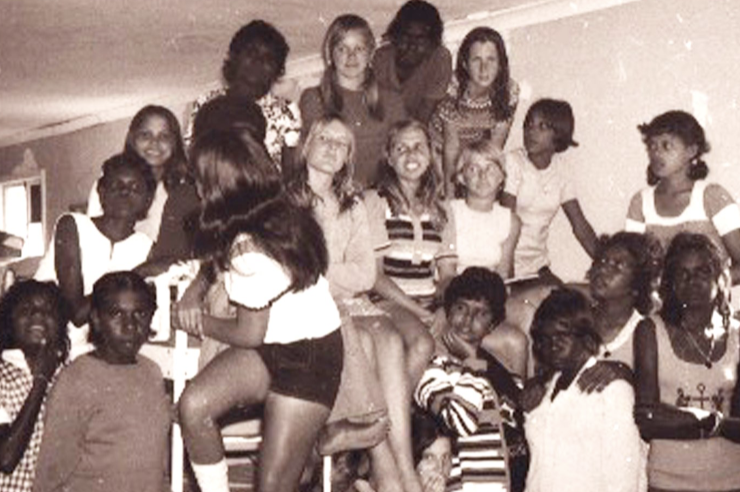

The Department of Education in Western Australia, called for volunteers to work with young people from remote in regional Western Australian schools. The camp was run overlooking the sea in wartime wooden shacks. I was an apprentice to an experienced though chaotic drama teacher, then one of the few in schools. He had a wild looking mane of hair and wore the mandatory tie-dye T-shirt and jeans. But then it was what are sometimes referred to as the hippy 70s. I was a student teacher partway through a degree in English literature with a passion for drama and film. But I had not yet started on any drama pedagogy. I was full of enthusiasm that was only matched by my ignorance.

The camp ran for five days, and each day there were drama activities interspersed with sporting and social activities and visits to factories. The camp participants were of mixed ages. Some were aboriginal students, what we now call First Nations Australians, but mostly they were kids in remote areas of a state that has a Million Square Miles of distance. None of them had been into the city before. None had done drama before.

We began each drama lesson with a warmup. Lots of closing eyes lying on the floor. Giggles and restlessness. A huge reliance on words like trust, focus and concentration.

Sitting in a mandatory circle, two students would be blindfolded and armed with long lances made of rolled up newspaper or a pillow from the dormitory and set to stalking each other guided by voiced signals from the other students. Repeated endlessly. Each time one of the stalking pair would erupt in a frenzy of furiously swiping air swishing (a long way from trust building) and cheers and whoops from the circle of onlookers.

Looking back, it’s a fair question to ask : What was the point of the activity? What was the drama learning? Participants seemed to be having fun, but what roles were being explored (beyond being aggressor)?

There was another activity of having students stand on the edge of the classroom desk and fall backwards into the cushioning arms of the other students. That truly was a trust exercise. Again, it’s fair to ask about the purpose of the activity in terms of drama learning.

There were improvisation games. Spontaneous scenes set up randomly with occasional glimpses of the life experiences of the camp participants. Imagine you are in the city for the first time and you have lost your money and you need to ask for help. The participants stumbled through these situations in ham fisted ways with a mix of shyness and tongue tied skill.

The other spectacular activity revolved around a huge parachute or sail. It was enormous, at least fifty metres wide. Outside on the shore in the dusk all camp participants ringed the parachute with instructions about how to hold the fabric (thumbs under, not over, to avoid any dislocations). In the stiff afternoon onshore breezes, there would a collective sighing heaving shouting and then the parachute lifting and lifting as everyone ran. The aim was for the parachute to fly and lift some students off the ground.

There were heaving breaths and wind blown red faces. Lots of laughing. The stated purpose was the sense of collaboration and cooperation implicit in all drama. There was certainly a sense of fun and participation. But what was the drama learning purpose?

I didn’t teach any specific drama lessons. But I did carry from the experience the need for committing everyone to a shared experience. I learnt the need to provide structure. It would be a time before I learned more about the purposes of warmups but I did sense their importance in providing focus and concentration (noted in all the drama teaching textbooks). There was a sense of “breaking the fourth wall” between teacher and students. In the sweaty closeness of the drama classroom there is a different dynamic from the desk bound world of teaching English Lit. But above all, I did have a sense of wanting to commit to this drama teaching world.

There is a serious purpose to the questions posed beyond an exercise in nostalgia.

Things were different then. I was different then.

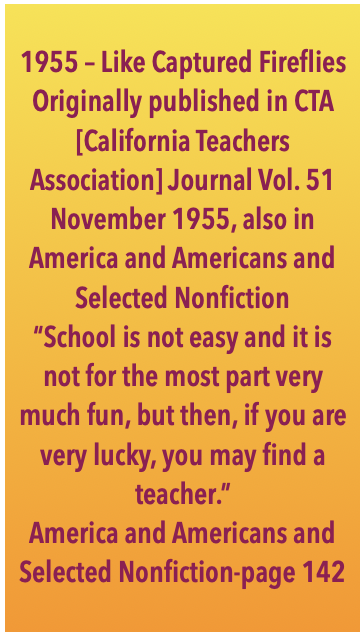

Drama teaching was not something I knew from my own schooling. There was none. Studying Shakespeare in school was reading Hamlet around the room desk bound. That activity was accompanied by the elderly teacher reading the Harley Granville-Barker Introduction to Shakespeare. It was mind numbingly deadly. At least I knew from my English teaching pedagogy that we would be focusing on understanding drama through practical exploration using voice and movement not simply cognitive note taking and regurgitation. So I was aware that drama teaching was committed to schooling that was significantly changed from my own schooling. It was a world of opportunity and possibility.

I was driven by what still drives me now all these years later: in drama we express and communicate ideas physically in time and space for others to share.

My drama teaching experiences on that camp were intense and memorable and thin on theory. There wasn’t much passing on of specific knowledge about the Elements of Drama. There wasn’t that much drama learning. But it was strong on enthusiasm, on the value of participating and risk taking. I don’t mean the risk taking of falling backward off tables into the hoped for arms of others. I am talking about stepping into an unknown, unscripted teaching space. I am talking about the riskiness of facing uncertainty, ambiguity, unknown unknowns. Drama teaching is not about following the prescriptions of those who have gone before us; there are no prewritten scripts, we are always improvising, stepping into the improvised space of making choices and facing consequences.

I didn’t recognise it at the time, but working on this drama camp was a springboard for a career.

It was also about making mistakes and living with the consequences of them. As the song goes, “mistakes, I’ve made a few”. In fact in my own teaching I wore as a badge of honour saying to students and teachers, one of the reasons I can talk about learning to teach is because if there’s a mistake to be made, I’ve probably made it. I remember, hearing or reading about Teacher-in-Role and being foolish enough to think I could try it. After all, I had done a bit of acting; it couldn’t be different could it? We might be humbled by our mistakes, but they only have meaning if we learn from them.

What is the best drama teacher education? Reflection and Reflexivity in action

How do we learn to become drama teachers? How do we become better drama teachers?

Drama teacher education is best modelled on our understanding of how we learn drama. We learn drama through practical, hands on and guided experience. With Vygotsky in mind, we learn reaching into our Zones of Proximal Development hand in hand with the Knowledgable Other.

In whatever form of learning to teach drama – university or community based, we keep several principles in mind. We belong to Guilds of Drama Educators. We serve apprenticeships. We are mentored. We make mistakes. We learn.

In my current work (semi-retired from the university but hanging about teaching one capstone unit) I teach about using Critical Incident Methodologies (Tripp 1993/2012). Critical Incidents in our professional practice are when, as the result of deep reflection on our theory and practice, we learn and we change our practice. Critical Incidents are not just any thing that happens in our day to day practice. They are not sensational, tabloid headlines or crises. Critical Incidents are created by our own minds seeing a problem that impacts on our professional practice.

Angelides (2001, Page 436 Table 1)provides a number of key questions to help us frame our perceptions/understanding of a Critical Incident.

Whose interests are served or denied by the actions of these critical incidents?

What conditions sustain and preserve these actions?

What power relationships between the headteacher, teachers, pupils, and parents are expressed in them?

What structural, organisational, and cultural factors are likely to prevent teachers and pupils from engaging in alternative ways?

In describing the drama workshop I have already posed some of those questions about the purpose and curriculum relevance of the activities. But it is also worth, probing deeper. Sometimes, looking back on drama teaching practice, it is possible to see signs of the drama teacher as hero. In the bland world of education, the colour and pizzazz of the charismatic drama teacher created mythologies. This prompts questions about who was the most powerful in the classroom. On the one hand, there was a focus on honouring student-centred ideas and experiences. Hand in hand there was the driving personality of the drama teacher. Drama teacher as cult leader or mystic or guru is a lingering question.

It is also possible to reflect about the valuing of drama by the school system. Drama was then seen as the sort of activity that was included on a school camp, but not in the mainstream curriculum offered to students. It was seen as “enrichment” for “disadvantaged” country kids. Drama had novelty not intrinsic valuing. It would take the length of my professional career in education to see the breaking down of these structural and cultural factors.

In other words, we need a more socially critical lens through which to reflect on the Critical Incident. “Only by attending to the values that are exposed by the incident that it is possible to achieve a sufficiently deep diagnosis to move beyond the practical problematic and into other kinds of professional judgement.” (Tripp 1993/2012, p. 112).

Professional growth requires both reflection and reflexivity. It is underpinned by the realisation that the creation of a Critical Incident from something that happened in my life, in turn creates something new in my life. It is change. It is transformational.

Bartlett (1990, in Joshi, 2018) presents some questions to be addressed while reflecting on personal critical incidents in a teaching career (adapted here to a drama education context):

Why did I become a drama teacher?

Do these reasons still exist for me now?

How has my background shaped the way I teach?

What is my philosophy of drama teaching?

Where did this philosophy come from?

How was this philosophy shaped?

What are my beliefs about drama learning?

What critical incidents in my training to be a teacher shaped me as a teacher?

Do I teach in reaction to these critical incidents?

These processes of standing back, looking at our practicer with aesthetic distance, serves to strengthen our drama teaching practice. Critical Incident approaches remind us of the need for what that Lincoln (1985) refers to perspectival shifts, for multiple views of the same phenomenon that may reveal multiple realities that are constructed by the participants in the same situation. There’s a need for going deeper into the taken-for-granted norms, to look behind the immediate, to interpret and make meaning.

It is important to note, that Critical Incident methodologies are not merely about describing something that happened. They rely on us identifying that there is an important, professionally significant problematic in the incident that stimulates reflection and reflexivity. In other words, the processes of analysis cause change of practice, rather than simple identification of an issue.

A practical example

Creating and analysing Critical Incident is a useful discipline for professional growth.

In 2013 I ran a workshop for DramaWest, the association for drama educators in Western Australia. It was based on the observations reported by my drama teacher education students that there was an indiscriminate and excessive use of Space Jump, one drama game. They reported whole class lessons being given over to this one game. Students loved it and demanded it as a way of avoiding other planned activities..

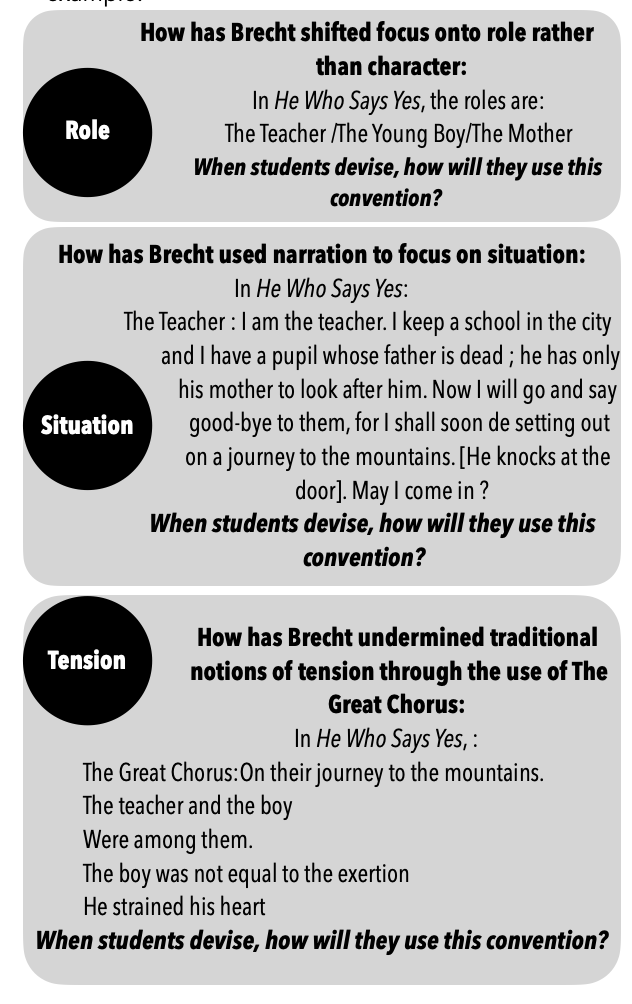

The principle of Space Jump is simple. A student inside a circle initiates an improvised drama action. The teacher, usually, calls “Space Jump”. The student freezes. Another student enters the scene and based on the frozen student’s image, initiates a different dramatic action that the first student must follow. In other words, the action is spontaneously jumped.

It is important to note that there is nothing intrinsically “wrong” with the Space Jump activity. It is the sometimes thoughtless and empty use of the activity that needs to be questioned. In the workshop that I ran, we explored ways of connecting the Space Jump activity to the Elements of Drama and the curriculum. By specifying which Element of Drama is focused on or by using the Space Jump to explore, say, specific forms and styles, it is possible to both engage with students’ enthusiasm for the activity and meet the need for specific learning outcomes.

Using Critical Incident approaches allowed for a questioning of practice and bringing about change.

I said at the beginning, sharing the question posed by this article, is more than an exercise in nostalgia. Celebrate our past with an eye to the future. There is always a little of that past me in my drama teaching today. All experience is still that “ arch wherethro’/ Gleams that untravell'd world whose margin fades. For ever and forever when I move” (Tennyson, 1842, Ulysses). The arc of time, as drama teaches us, is not measured in moments on the clock. Our practice, like art, is long.

All images by Robin Pascoe, 1976.