Drama Tuesday - An afternoon matinee

/Liz and I went to the St Mary’s Anglican Girls School production of Anastasia The Musical. There are Old Girl connections with the school for Liz at different levels: Liz was a scholarship girl at the school when it moved to the Karrinyup site; the director of the production is the daughter of Liz’s best friend from St Mary’s and has just moved to teach there and this is her first production.

Effective production with pace and energy, advancing the narrative with good drive and efficient scene changes with two small revolves on stage. Strong singing performances Anastasia The Musical is not a well known production and I haven’t seen it produced before. The music by Flaherty and Ahrens, bubbles along pleasantly.

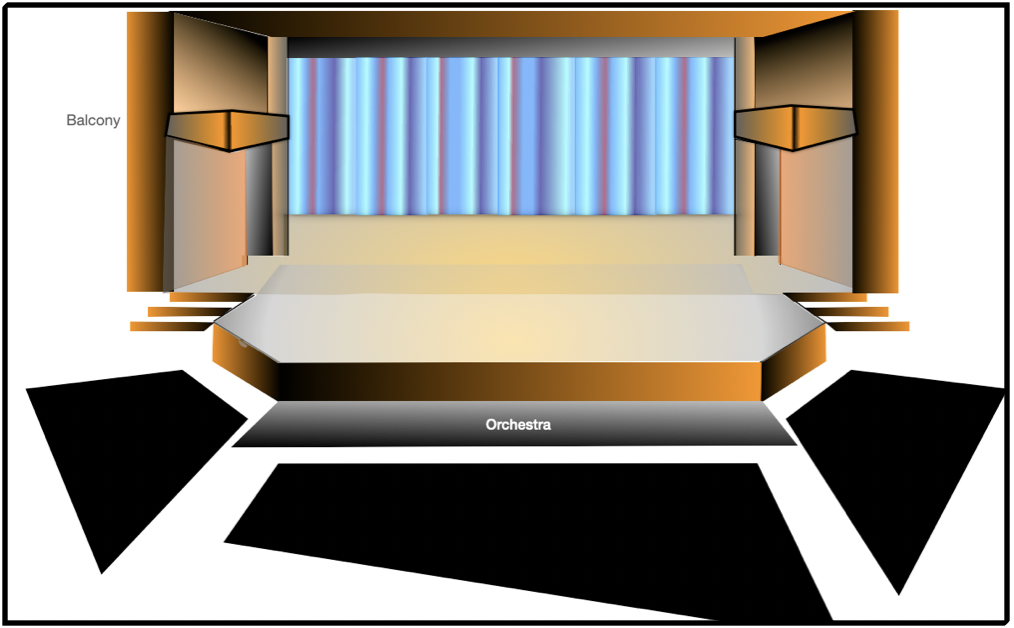

This is only the second time I’ve been at the Lady Wardle Performing Arts Centre; the other time was for a BlackSwan production of Cosi.

Two interesting lines of thought: the venue and the choice of production.

School venues

There are now a significant number of schools in the Perth region with these large scale venues. This trend reflects commitment to performing arts and it is interesting to see the design approach.

This theatre seating 518 in three blocks that fan wide from the stage. The stage is wide and projects into the audience though is not a full thrust stage. As I sat in the audience, seating quite heavily raked above the action, I kept thinking about the challenges for directors There’s quite a distance to the wings from centre stage and the action is projected forward. There was a tendency for actors to move downstage centre in every scene. The nicely presented stage images relied on a sense of symmetry. The Juliet balconies on either side provide opportunities. But the width of the stage presented a need for brisk exits and entrances to maintain the pace.

The sound balance with the orchestra being amplified also presents challenges.

Production Choices for Schools

My other line of thought was about the choice of Anastasia. Not because it was new – we are always looking for fresh and interesting productions to challenge and excite our students. I was thinking about the issues of choosing plays for single gender schools, like St Mary’s. This production brought in four males students from other schools (one from Liz’s school).

But during the first act, I noticed that the action resolved largely around four roles – one female, the role of Anastasia; the other three were male. There was a fleeting scene with the Dowager who figured strongly in Act 2. There were many other on stage chorus roles, plenty of colour and spectacle, yet the dramatic action was narrowly focused. The second act added developed the role of the Dowager and added another extended major female role. As a script, Anastasia is actually a star vehicle. This production relied very much on the strong male leads with relatively limited roles for female students.

But this script is indicative of the dilemma faced by many teachers selecting productions. The balance of roles for students often doesn’t reflect the reality of enrolments.

Some single gender schools, resolve the issues by partnering with other single gender schools. Even in co-educational students, particularly where there are more female students than males, there are still issues about the balance of roles available.

What is the best repertoire for single gender schools?

What is the best music theatre repertoire for single gender schools?

Or for schools in general?

This is particularly an issue in choosing plays that provide strong roles for female students. We all know how difficult it can be if you want to stage Shakespeare’s plays.

You could take the line (as one feisty drama teacher did) and simply cast from within the actors available in the school and have some students play cross gender roles. [Certainly, in my schooling in an all boys school in another century we did that and my first on stage role was as one of the “Sisters, Cousins and Aunts” in The Pirates of Penzance.] Earlier this year we saw the John Curtin College of the Arts production of Jesus Christ Superstar with female leads playing the role of Jesus. There is the argument for “blind casting” made. But the climate for arts education is supercharged and there are new challenges for all.

Quick snap of the theatre at the end of the production as the audience were filing out after applause.

Drama Thursday - The Gingerbread Man Visits Year 1

/Thursday is assembly day at D. Primary School. It’s Room A3 Year One students’ turn. As the projected slide announces, they are performing The Gingerbread Man.

The assembled school sing along to the recording of the upbeat Australian National Anthem with the didgeridoo intro. The Student Councillors lead the presentation of honour certificates. There’s a few “dad” jokes from the Deputy Principal, innocent and silly, drawing groans from the assembled audience. The school song (with the odd scansion) is sung conducted by the enthusiastic music teacher. The student and teacher audience members sit in plastic chair rows. Parents edge the covered area shivering a little in the crisp air.

The Year 1 students have been sitting on the stage spread in a regular checkerboard pattern. They have conned their lines. Rehearsed ( William, with rolled eyes, tells us that the only thing they’ve done this week is rehearsed their lines).

Narrators line up to step on the box behind the podium. Other students sit in clumps in costumes improvised by busy mums. The little old couple sit awkwardly next to their cardboard box painted as an oven. Busy Year six students scurry in and out thrusting microphones at the line speakers (sometimes getting the right person). Lines are read or stumbled past. At one point the teacher rushes from her seat in the front row to help one of the narrators turn the A3 size script. The chase of the gingerbread man ambles aimlessly round and round. Then suddenly it’s finished.

There are more certificates.

The Year Ones thank the audience and sends them back to class.

Parents rush the stage as the photos are taken.

Like a released spring the Year Ones cavort and run free on the stage. There’s a frenzy of relief and exuberance.

The drama teacher in me wonders: is this as good as it gets!

There’s an obvious mismatch of expectations. Here the hope is performance. The way the audience are ranged, the structuring, the reliance on script (tired, cliched, word driven), set up a performance paradigm. The drama experience is narrowed and limited. Controlled.

How could it be different?

Let’s begin by saying to the assembled audience: today we are not performing a play to you; we are sharing our drama making experience.

Then: teacher in role of leader begins a moved visualisation with all the children (edging into the drama experience): Once there was a time when we were making gingerbread. Can you smell the things we need to make the gingerbread. Can you feel the flour in our fingers? Can you smell the ginger…? Let’s put these ingredients into a big bowl and stir the all up

Placing two chairs: In this telling of the story there was an old man and an old woman. Can you imagine them, sitting in their chairs. They were very very old but still loved life. Who would like to be in these roles? Invite two children to become the roles. Add a couple of simple props to indicate the roles: a hat and a scarf.

How do you think they might sit? How might they move? How could we show that they are very very old?

They loved gingerbread. Do you like gingerbread? What does it taste like?

What do you think they might say about their gingerbread?

And so on through the emergence of the gingerbread man from the oven; the bolshie challenge to authority; the escape; the fox and the river. Use simple storage is such as still image/tableau. When it comes to the chase, use slow motion. Map the chase specifically. Create and add new roles. Engage students in drama making.

In other words, shift the whole paradigm.

Of course, it’s risky.

Of course, it doesn’t have the element of control. Things may happen that you don’t anticipate.

But, ask important questions

Who is the drama for at this age?

What is the relevant learning?

How do we make this age appropriate and developmentally appropriate learning?

There are a couple of questions to answer.

What will the assembly audience see!

They will see and hear process rather than product. Or a different kind of product. And that needs explaining/preparing.

Isn’t this putting the teacher more important than the students. It’s not about me. It’s all about the kids!

That question underlines the issue of understanding the role of the teacher as the co-constructor of meaning in learning.

I hear the protests: this isn’t much of an assembly item for the rest of the school!

How do we know if it hasn’t been tried? How do we school the school about doing things differently. There is a time and a place for the “performance of drama”. But there is also a place for celebrating the immediacy and joy of the drama experience itself. And that is what truly matters most.

Was it a good experience for the students?

What did they learn?

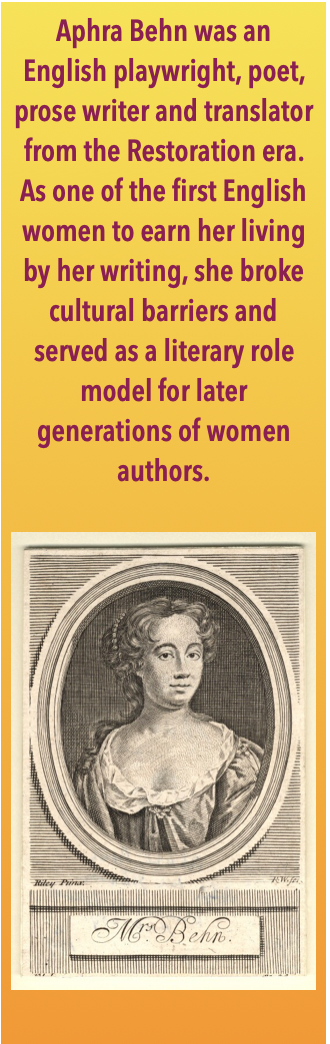

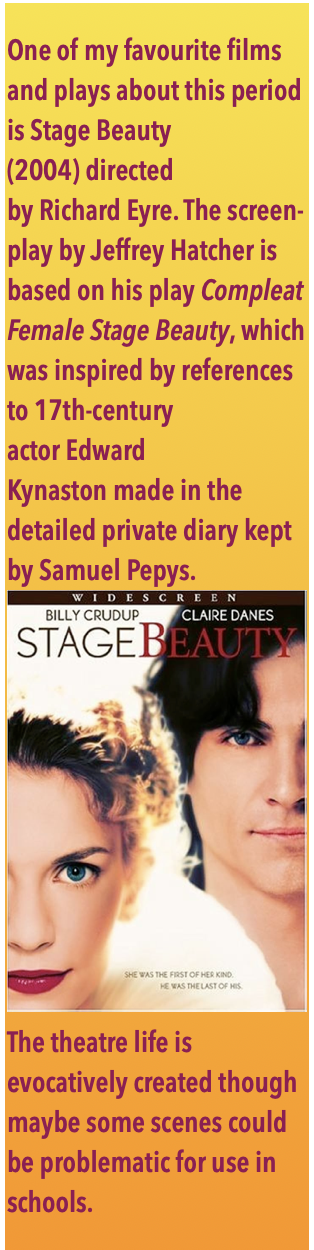

Drama Tuesday - Giving Voice to the silenced

/In my last post, I was immersed in the stews of Elizabethan London in Mat Osman’s The Ghost Theatre. This post jumps forward to Restoration Drama but is still immersed in the roiling hotpot of London theatre in a novel that features Aphra Bean told through the eyes of a fictive young woman named Tribulation Johnson. It's 1679 and the fierce and opinionated Tribulation Johnson is catapulted into the tumult, politics and colour of Restoration London and its lively theatre scene. Cast out from her family as ungodly and unworthy - Tribulation arrives in London on her own dressed in her dead brother’s clothes. Through Aphra, a cousin, Tribulation is immersed in the seedy, shabby yet fascinating world of the Dorset Garden Theatre, owned by the King’s brother, the Duke of York, one of the two permanent theatres in London. The other, owned by the King, Charles II, is Drury Lane. She meets the famed and the notorious. The story is redolent with names: writers and playwrights such as Samuel Pepys, Dryden; actors such as the Bettertons; politics; spies; treachery. And, of course, Aphra Bean herself. They are all brought to life through lively writing with strongly researched attention to detail.

The strength of this novel by Karen Brooks is the potent recreation of life in Restoration Theatre. The backstage detail, the technical and personal interweaving of the roles of the prompt, the actors and the audience, the cross referencing of plays and playwrights, provide a plausible and interesting imagined portrait of Restoration drama.

More than that, the story weaves in a powerful polemic about voices that are heard or suppressed. The subtitle of Brook’s title – A Woman Writes Back – signals the key theme.

This short excerpt from an imagined conversation between Aphra and Tribulation crystallises a challenging discussion point for drama students.

‘I’ve always believed,’ said, Aphra firmly, indicating I should pull up a chair, plays ought to be political – especially, when the time calls for commitment. As a woman, I cannot argue in Parliament or even in a coffee-house. I cannot vote in a guild nor run an office. I cannot take arms but I can write. My plays - the words I put in the characters' mouths, the plots, and themes, whether they are couched in comedy or drama, are like secret instructions to the people: instructions in things it's impossible to insinuate into them in any other way?’

Pages of scrawled notes, drafts of new plays and other writings fanned the surface of her desk. ‘You see yourself as teaching the audience, giving them lessons they don't even know they're having,’ I said as understanding dawned. Some plays were so silly, so salacious and outrageous, and yet Aphra was right. Just because something was humorous or bawdy didn't make it less profound. That was the shallow dressing in which deeper meanings were buried.

Aphra smiled. I loved her smile, the way it made her eyes glimmer, dance in the soft light of candles. The way her lips parted to reveal her even, creamy teeth. 'That's certainly one way to consider it. Maybe what I do is reach, rather than teach. That's at least something, don't you think?’ She placed her hand over mine. ‘Name one other way women can do that’. She waited. ‘No. neither can I. Through words - words I write, and which actresses like Elizabeth Barry, Mary Lee, Elizabeth Currer, your Charlotte and the rest perform - we speak to the audience, to other women especially. The hear us. They see us. It’s one of the reasons I make sure there's plenty for my female characters to say. There's a strength in numbers, Tribulation. Every general knows that. What's life but a constant battle for women? We must recruit others and join forces where we can. It’s only when we unite we have any might, that our voices are heard, and maybe even listened to. It’s why men work so hard to keep us apart, sow discord, interrupt, call us abhorrent names, sully reputations before they're even made. They try to silence us, turn us against each other because they're afraid of what we’ll achieve if we work together?’ She shifted on her chair, grimacing as the leg that sometimes ached caused her pain. ‘I've said it before, and I'll say it again. Fear makes men angry. Those they fear the most bear the brunt of that fury.’

"They must be terrified of you.’

Aphra gave a droll look. ‘Perhaps. Mind, there are still women who perceive females like me, like those in the Duke's and King's Companies, like Nell Gwyn, Moll Davis, the publisher, Joanna Brome, like you, as enemies. They take the men's part, become willing warriors for their causes, take up arms against those they should fight beside.

In my experience, women can make the very best of allies, but also the worst of adversaries.' She sighed. 'It's hard to forge ahead when you're always watching your back- as you've had cause to learn of late.’

I took a deep breath. ‘From here on in, I'll watch yours, Aphra.’ It was a vow.

Page 114-115

How do we give voice (if it is ours to “give”).

The challenge for drama teachers is giving voice to those silenced by history, culture, gender, identity and time. There are interesting case stories of how this challenge is being met (see, for example, the story of the development of Australian drama in a swamp of imported productions, women’s drama, First Nations Drama in Australia). The dilemma for drama teachers is cutting through the competing clamouring voices calling for recognition. In lifting up one voice, can we also drown out other voices?

Curriculum theorists remind us of the different types of curriculum such as the “hidden curriculum” – “the lessons which are learned but not openly intended to be taught in school such as the norms, values, and beliefs.”

They also remind us of the “Null Curriculum” – “… the options students are not afforded, the perspectives they may never know about, much less be able to use, the concepts and skills that are not part of their intellectual repertoire” (Eisner,1985, p. 107).

Every drama teacher, every teacher, makes choices. Choose wisely.

Bibliography.

Karen Brooks, 2023, The Escapades of Tribulation Johnson, Harper Collins, Sydney.

The appendices list the plays mentioned and the cast of characters as well as providing interesting background material on development of the narrative. Brooks is an Australian author.

Drama Tuesday - Drama education shape shifting

/Reflection from the Drama Australia National Conference June 2-3 2023.

Drama is a shape shifter. Not quite in the dictionary meanings but in the sense that in drama when we take on role, we shift into the role.

I was struck by thinking about this during the Drama Australia conference over the weekend. It’s not necessarily a new thought but one to explore in this moment.

Drama teachers are adept share shifters.

When the drums of literacy beat, drama teaching shifts focus to bring to the foreground how drama supports language learning and use. When there is a focus on life skills, we assert the role of drama in building confidence. Drama claims a space in STEAM education with slick speediness. We hear calls for arts integration as the solution to the crowded curriculum and drama as a method. Feminist concerns remind us of the power of drama in raising issues. Similarly, as the currency of indigenous or First Nations inclusion increases, we need the reminders of the value of drama in that field.

That is not to say argue against a need for greater diversity in drama education.

Maybe this is a mechanism for coping with a search for reassuring relevance. Maybe it’s also politically savvy. In all of this soft shoe shuffling however, it is important to never lose sight of what drama is fundamentally and why it is a necessary part of a complete education. We need to remind ourselves that as each competing priority rings its bell, drama education is not just a vehicle for the topical or the passing educational pinup. We need to be alive to how the dominating voices are swamping or taking up all the available oxygen for arts education. We need to be true to the fundamental nature and purpose of drama education. In a world twisting and shaping itself to meet shifting educational fads, we need to plant our feet on the stage and deliver our lines with firmness.

Drama is wily. Drama is clever. Drama is political and social and cultural. Drama is all these things and we in drama education have learnt the lesson well. But drama education needs to be true to its purpose.

I know these can be seen as controversial thoughts. It’s not my intention to upset applecarts or to disrupt the parade. But sometimes these rebellious thoughts need a place in the conversation.

What do you think?

Drama Tuesday - Performing Arts Perspectives 2023

/For the 27th time, outstanding performances of students completing Year 12 courses in Dance, Drama and Music were showcased to a packed Perth Concert Hall.

It is always interesting to reflect on the topics that emerge in the drama performances.

In the Original Solo Performance Good Old Trip by Gia Mairata, a delightful elderly grandmother living alone with her parrot is given a gift of brownies made by her grand daughter special brownies laced with certain substances. Played for laughs with gusto. A crowd pleaser with the youthful audience.

Estella Glencross created The 20th of July Plot, focusing on the moral dilemma facing the plotters of an assassination attempt on Hitler. An interesting concept explored though I felt the physicality of the role was under explored.

Elijah Kanganas gave a spirited realisation of William breaking free from convention in Free Will.

The Tiger Mum by Madeline Kelly explored the dark world of dance mums with strongly recognised humour entertaining the audience.

Once again we saw trends towards 1) strong physicalisation fully realised use of space and time and flexibility in movement; 2) clever use of sound (though thankfully not every performance was bathed in sound); and, 3) use of humour (which can be a double edged sword unless well managed).

The three scripted monologues showed range.

Words of Advice for Young People by Ioanna Anderson performed by Charlotte Moody

Kailee Young performed med Richard III by William Shakespeare with paper cutouts for the murdered princes.

Actor by Steven Berkof was performed with amazing vocalised sound effects and physicality by Jack Hadlow (underpinning once again the power of voice used well).

As always, a Concert Hall venue is not necessarily the most suitable for actors and the use of miking and amplification, while better this year, produced reverberant tone.

Each year is a window into the drama mind of young students. And a tribute to those who created and sustained this annual event.

Drama Tuesday - Do you remember your first drama lesson?

/Critical Incident Methodologies for Future Practice

Robin Pascoe,

Honorary Fellow, School of Health and Education, Murdoch University. Immediate Past President IDEA

I don’t pose that question as an exercise in nostalgia. This is a serious question designed to stimulate reflective practice. Our first experience is drama teachers often shape us and leave indelible marks. Before you read on, take time to reflect on your first drama teaching experiences. What do you remember? What was positive? What do you back on perhaps with a smile or a cringe about your “mistakes”?

For me, my first drama teaching was in a different century, and we all know that the past is a different country, and they do things differently there.

Things were different then

The Department of Education in Western Australia, called for volunteers to work with young people from remote in regional Western Australian schools. The camp was run overlooking the sea in wartime wooden shacks. I was an apprentice to an experienced though chaotic drama teacher, then one of the few in schools. He had a wild looking mane of hair and wore the mandatory tie-dye T-shirt and jeans. But then it was what are sometimes referred to as the hippy 70s. I was a student teacher partway through a degree in English literature with a passion for drama and film. But I had not yet started on any drama pedagogy. I was full of enthusiasm that was only matched by my ignorance.

The camp ran for five days, and each day there were drama activities interspersed with sporting and social activities and visits to factories. The camp participants were of mixed ages. Some were aboriginal students, what we now call First Nations Australians, but mostly they were kids in remote areas of a state that has a Million Square Miles of distance. None of them had been into the city before. None had done drama before.

We began each drama lesson with a warmup. Lots of closing eyes lying on the floor. Giggles and restlessness. A huge reliance on words like trust, focus and concentration.

Sitting in a mandatory circle, two students would be blindfolded and armed with long lances made of rolled up newspaper or a pillow from the dormitory and set to stalking each other guided by voiced signals from the other students. Repeated endlessly. Each time one of the stalking pair would erupt in a frenzy of furiously swiping air swishing (a long way from trust building) and cheers and whoops from the circle of onlookers.

Looking back, it’s a fair question to ask : What was the point of the activity? What was the drama learning? Participants seemed to be having fun, but what roles were being explored (beyond being aggressor)?

There was another activity of having students stand on the edge of the classroom desk and fall backwards into the cushioning arms of the other students. That truly was a trust exercise. Again, it’s fair to ask about the purpose of the activity in terms of drama learning.

There were improvisation games. Spontaneous scenes set up randomly with occasional glimpses of the life experiences of the camp participants. Imagine you are in the city for the first time and you have lost your money and you need to ask for help. The participants stumbled through these situations in ham fisted ways with a mix of shyness and tongue tied skill.

The other spectacular activity revolved around a huge parachute or sail. It was enormous, at least fifty metres wide. Outside on the shore in the dusk all camp participants ringed the parachute with instructions about how to hold the fabric (thumbs under, not over, to avoid any dislocations). In the stiff afternoon onshore breezes, there would a collective sighing heaving shouting and then the parachute lifting and lifting as everyone ran. The aim was for the parachute to fly and lift some students off the ground.

There were heaving breaths and wind blown red faces. Lots of laughing. The stated purpose was the sense of collaboration and cooperation implicit in all drama. There was certainly a sense of fun and participation. But what was the drama learning purpose?

I didn’t teach any specific drama lessons. But I did carry from the experience the need for committing everyone to a shared experience. I learnt the need to provide structure. It would be a time before I learned more about the purposes of warmups but I did sense their importance in providing focus and concentration (noted in all the drama teaching textbooks). There was a sense of “breaking the fourth wall” between teacher and students. In the sweaty closeness of the drama classroom there is a different dynamic from the desk bound world of teaching English Lit. But above all, I did have a sense of wanting to commit to this drama teaching world.

There is a serious purpose to the questions posed beyond an exercise in nostalgia.

Things were different then. I was different then.

Drama teaching was not something I knew from my own schooling. There was none. Studying Shakespeare in school was reading Hamlet around the room desk bound. That activity was accompanied by the elderly teacher reading the Harley Granville-Barker Introduction to Shakespeare. It was mind numbingly deadly. At least I knew from my English teaching pedagogy that we would be focusing on understanding drama through practical exploration using voice and movement not simply cognitive note taking and regurgitation. So I was aware that drama teaching was committed to schooling that was significantly changed from my own schooling. It was a world of opportunity and possibility.

I was driven by what still drives me now all these years later: in drama we express and communicate ideas physically in time and space for others to share.

My drama teaching experiences on that camp were intense and memorable and thin on theory. There wasn’t much passing on of specific knowledge about the Elements of Drama. There wasn’t that much drama learning. But it was strong on enthusiasm, on the value of participating and risk taking. I don’t mean the risk taking of falling backward off tables into the hoped for arms of others. I am talking about stepping into an unknown, unscripted teaching space. I am talking about the riskiness of facing uncertainty, ambiguity, unknown unknowns. Drama teaching is not about following the prescriptions of those who have gone before us; there are no prewritten scripts, we are always improvising, stepping into the improvised space of making choices and facing consequences.

I didn’t recognise it at the time, but working on this drama camp was a springboard for a career.

It was also about making mistakes and living with the consequences of them. As the song goes, “mistakes, I’ve made a few”. In fact in my own teaching I wore as a badge of honour saying to students and teachers, one of the reasons I can talk about learning to teach is because if there’s a mistake to be made, I’ve probably made it. I remember, hearing or reading about Teacher-in-Role and being foolish enough to think I could try it. After all, I had done a bit of acting; it couldn’t be different could it? We might be humbled by our mistakes, but they only have meaning if we learn from them.

What is the best drama teacher education? Reflection and Reflexivity in action

How do we learn to become drama teachers? How do we become better drama teachers?

Drama teacher education is best modelled on our understanding of how we learn drama. We learn drama through practical, hands on and guided experience. With Vygotsky in mind, we learn reaching into our Zones of Proximal Development hand in hand with the Knowledgable Other.

In whatever form of learning to teach drama – university or community based, we keep several principles in mind. We belong to Guilds of Drama Educators. We serve apprenticeships. We are mentored. We make mistakes. We learn.

In my current work (semi-retired from the university but hanging about teaching one capstone unit) I teach about using Critical Incident Methodologies (Tripp 1993/2012). Critical Incidents in our professional practice are when, as the result of deep reflection on our theory and practice, we learn and we change our practice. Critical Incidents are not just any thing that happens in our day to day practice. They are not sensational, tabloid headlines or crises. Critical Incidents are created by our own minds seeing a problem that impacts on our professional practice.

Angelides (2001, Page 436 Table 1)provides a number of key questions to help us frame our perceptions/understanding of a Critical Incident.

Whose interests are served or denied by the actions of these critical incidents?

What conditions sustain and preserve these actions?

What power relationships between the headteacher, teachers, pupils, and parents are expressed in them?

What structural, organisational, and cultural factors are likely to prevent teachers and pupils from engaging in alternative ways?

In describing the drama workshop I have already posed some of those questions about the purpose and curriculum relevance of the activities. But it is also worth, probing deeper. Sometimes, looking back on drama teaching practice, it is possible to see signs of the drama teacher as hero. In the bland world of education, the colour and pizzazz of the charismatic drama teacher created mythologies. This prompts questions about who was the most powerful in the classroom. On the one hand, there was a focus on honouring student-centred ideas and experiences. Hand in hand there was the driving personality of the drama teacher. Drama teacher as cult leader or mystic or guru is a lingering question.

It is also possible to reflect about the valuing of drama by the school system. Drama was then seen as the sort of activity that was included on a school camp, but not in the mainstream curriculum offered to students. It was seen as “enrichment” for “disadvantaged” country kids. Drama had novelty not intrinsic valuing. It would take the length of my professional career in education to see the breaking down of these structural and cultural factors.

In other words, we need a more socially critical lens through which to reflect on the Critical Incident. “Only by attending to the values that are exposed by the incident that it is possible to achieve a sufficiently deep diagnosis to move beyond the practical problematic and into other kinds of professional judgement.” (Tripp 1993/2012, p. 112).

Professional growth requires both reflection and reflexivity. It is underpinned by the realisation that the creation of a Critical Incident from something that happened in my life, in turn creates something new in my life. It is change. It is transformational.

Bartlett (1990, in Joshi, 2018) presents some questions to be addressed while reflecting on personal critical incidents in a teaching career (adapted here to a drama education context):

Why did I become a drama teacher?

Do these reasons still exist for me now?

How has my background shaped the way I teach?

What is my philosophy of drama teaching?

Where did this philosophy come from?

How was this philosophy shaped?

What are my beliefs about drama learning?

What critical incidents in my training to be a teacher shaped me as a teacher?

Do I teach in reaction to these critical incidents?

These processes of standing back, looking at our practicer with aesthetic distance, serves to strengthen our drama teaching practice. Critical Incident approaches remind us of the need for what that Lincoln (1985) refers to perspectival shifts, for multiple views of the same phenomenon that may reveal multiple realities that are constructed by the participants in the same situation. There’s a need for going deeper into the taken-for-granted norms, to look behind the immediate, to interpret and make meaning.

It is important to note, that Critical Incident methodologies are not merely about describing something that happened. They rely on us identifying that there is an important, professionally significant problematic in the incident that stimulates reflection and reflexivity. In other words, the processes of analysis cause change of practice, rather than simple identification of an issue.

A practical example

Creating and analysing Critical Incident is a useful discipline for professional growth.

In 2013 I ran a workshop for DramaWest, the association for drama educators in Western Australia. It was based on the observations reported by my drama teacher education students that there was an indiscriminate and excessive use of Space Jump, one drama game. They reported whole class lessons being given over to this one game. Students loved it and demanded it as a way of avoiding other planned activities..

The principle of Space Jump is simple. A student inside a circle initiates an improvised drama action. The teacher, usually, calls “Space Jump”. The student freezes. Another student enters the scene and based on the frozen student’s image, initiates a different dramatic action that the first student must follow. In other words, the action is spontaneously jumped.

It is important to note that there is nothing intrinsically “wrong” with the Space Jump activity. It is the sometimes thoughtless and empty use of the activity that needs to be questioned. In the workshop that I ran, we explored ways of connecting the Space Jump activity to the Elements of Drama and the curriculum. By specifying which Element of Drama is focused on or by using the Space Jump to explore, say, specific forms and styles, it is possible to both engage with students’ enthusiasm for the activity and meet the need for specific learning outcomes.

Using Critical Incident approaches allowed for a questioning of practice and bringing about change.

I said at the beginning, sharing the question posed by this article, is more than an exercise in nostalgia. Celebrate our past with an eye to the future. There is always a little of that past me in my drama teaching today. All experience is still that “ arch wherethro’/ Gleams that untravell'd world whose margin fades. For ever and forever when I move” (Tennyson, 1842, Ulysses). The arc of time, as drama teaches us, is not measured in moments on the clock. Our practice, like art, is long.

All images by Robin Pascoe, 1976.

Drama Tuesday - The fibs we tell about arts education

/In my childhood, a fib with the little lie. It’s not an out and out dishonesty, not a deliberate untruth. It was a minor, bending of truth, sometimes to protect someone’s feelings, avoid embarrassment, or plaster over difficult situations.

In teacher education, we are often fibbing to our students that we provide sufficient arts teacher education. We perpetrate this mistruth with the best of intentions: we are making the best of a bad situation with the time we have available, we say. Or, we blame someone else – the managerialist system, the usual Neo-liberal, whipping boys! But deep down, we know that we are glossing over the truth.

There is the temptation to throw up our hands in exasperation, and to just give up.

But maybe we need some truth and reconciliation!

No one likes truth tellers. We as a society have a bad habit of punishing them. Or dismissing them as dissidents. But if we truly care about Arts education and its place in the education of all students, we have to call out the fibbers, the masters of misdirection, the sleight of mind, the liars and cheats.

There is a deeper issue: a deeper state of denial. If there are fibbers that are also these deniers. And deniers (such as climate change deniers!) are maybe worse. They cling to their articles of faith blindly. With bombast there’s a rather senior education department principals who maintains the faith and claims to me without even a twitch of irony that “the state of Arts education in schools is healthy”, adding for emphasis, “Teachers are well prepared for teaching the arts in their classrooms”. Later, ironically, over dinner, he’s outlined that his drama training consisted of a lecturer dictating drama games to write down.

If you are in a state of denial of course all in the garden is roses and there’s no manure.

The reality of arts education, and contemporary teacher education is that it is not healthy. Think about the courses where the arts are included in units about integrating curriculum. Without any sense of shame there are units that cover HASS/HPE/The Arts in one semester. There are teacher education courses that have 20 contact hours early in a four year degree course. This sort of practice reinforces the current pragmatics of schools that argues that all students need is integrated curriculum which is the panacea for time-poor teachers Or there is a focus on “doing things” in the name of arts learning ignoring the underlying purpose of arts curriculum.

At one level, fibs are inevitable. If we face too much truth telling, we might go mad. But maybe it’s time to stop shrugging our shoulders. Time to face up to a reality check.

What do you think!

Drama Tuesday - A Primer For Arts Education

/A quick Primer on teaching the Arts in schools

Sometimes it is useful to restate fundamental principles about teaching and learning the arts. You answer questions about:

1. Being clear about why you are teaching the arts

Teaching the Arts begins with a choice on your part: you choose to teach the arts so your students can know and understand the arts in their own lives and can use the arts to express their ideas and feelings and communicate them with others.

But your teaching always begins with a choice on your part.

While Curriculum Authorities can provide syllabuses and mandates, you need to ultimately see the purpose and value of your students following those curriculum mandates. You begin by answering a fundamental question: why am I including the arts in the priorities I make about what is important for my students to know, do, value and learn.

2. Being clear about what you are teaching your students to know, do and value in the arts

There are often misconceptions about what you teach in the arts.

Let’s start with the BIG IDEA.

You are teaching students to be artists and audiences for the arts in their own lives, cultures and societies. You are teaching students how they find their personal, social and cultural identities through making and responding to the arts.

To achieve that BIG IDEA:

You provide opportunities for students to experience the arts. They use their senses to see and hear and feel arts experiences. They experience a wide variety of arts immediately, directly and relate them to their own lives.

In that context, you provide students opportunities to make their own arts - to express and communicate ideas, feelings, experiences directly through the mediums of the art forms.

What you teach in the arts is therefore something more than singing a song or improvising a dance or drama or making a colour wheel, or recording a video – it might involve those activities but not on their own or in isolation. What is being taught to students is how the arts provide ways of expressing and communicating and why that is an important life value. They are applying their learning about the arts from experiencing the arts, to making the arts. They are being taught to be artists and audiences.

Another way of thinking about what students are learning is that the chosen arts activity for a lesson, is a vehicle for the broader learning, rather than just an activity to complete. For example, how does the song being song in the lesson, add to or develop what students know about the elements of music and the role of music in people’s lives. This is, after all, the question we ask ourselves as teachers about any learning activity in any curriculum area: how does this chosen learning activity contribute to students’ learning? The activity must always be the vehicle for the learning.

3. Being clear about how students learn in the arts

Learning in the arts is experiential, hands-on and practical.

Students learn the arts by making the arts, by experiencing and responding to the arts, by applying their knowledge and skills – what they have learnt – to their own making and responding in the arts.

Learning the arts is experiential. It is through direct hands on experiences of the arts as audiences, and as makers and artists, that students learn.

That does not mean that there are not times when you are directly teaching students about the arts. It might be that you are demonstrating a specific skill or technique. It might be that you are sharing knowledge about the history and cultural, social and personal contexts of specific arts experiences tracing continuity and change over times, places and cultures. These are the times when you, as a knowledgeable other share your knowledge to provide “zones of proximal development” (Vygotsky) with your students.

Learning in the arts is also progressive.

It is developmental, recognising that students learning needs are different according to their ages and their physical, social, emotional development. In choosing arts activities they need to be age and developmentally appropriate for your students.

It is organised and structured. Students learn in the arts through a widening spiral of experiences that provide increasing challenge. A spiral curriculum model that is not haphazard or random. Students have a clear understanding of how what they are learning today builds on what they have already learn – and which also is leading to further future learning.

4. Being clear about your role in in your students’ learning in the arts

Your role in your students’ learning is clear.

You guide. You inspire. You model. You share knowledge. You facilitate. These are overlapping not mutually exclusive roles.

You can sum up your role as the co-creator of learning. Your provide contexts, materials, knowledge as required, supportive and safe environments. You provide guidance. But, you are not the director of the show, the invisible hand wielding the brush, the composer of the music. You model your own creativity alongside your students as they create, but you given them voice and agency – while modelling your own.

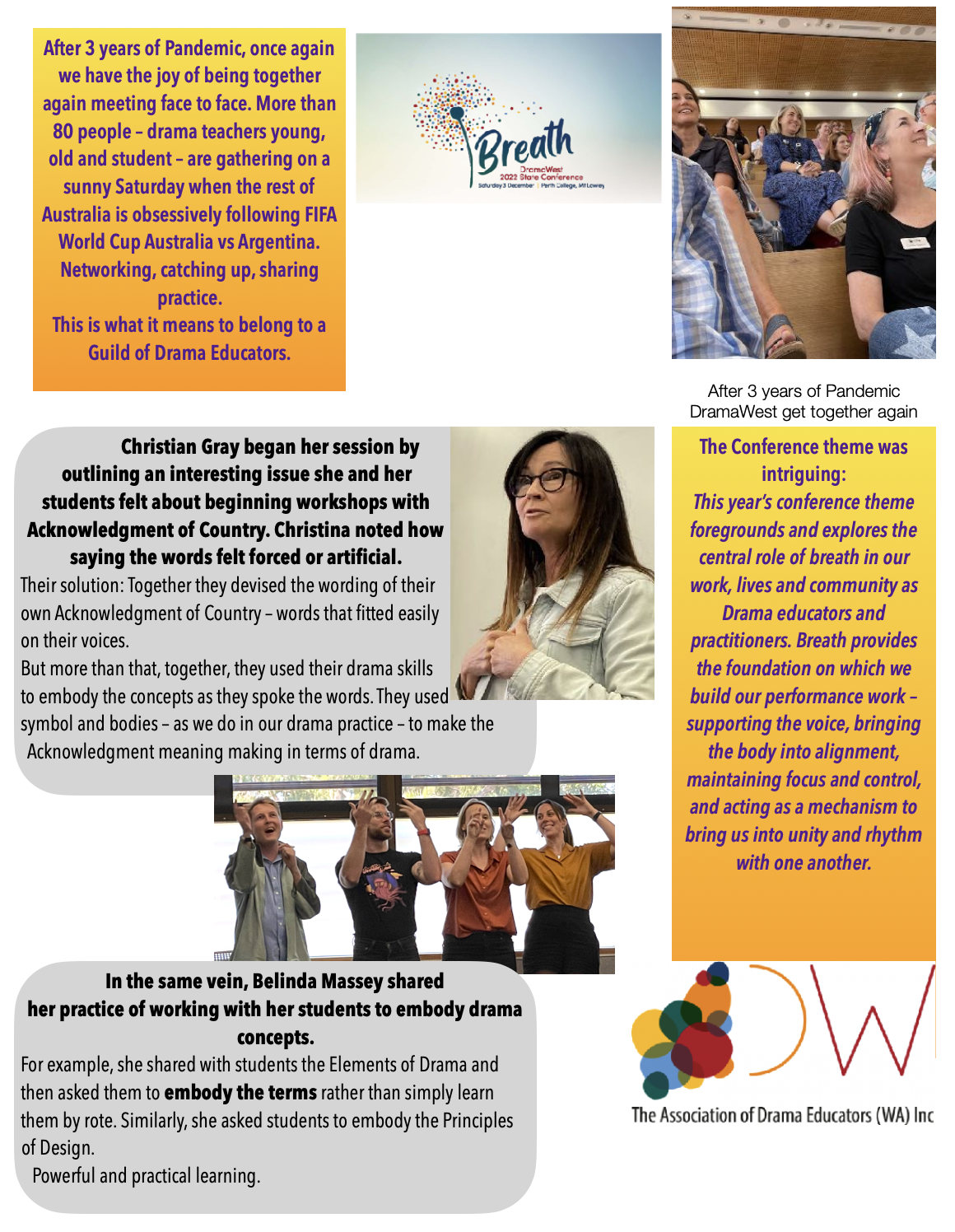

Drama Tuesday - DramaWest Conference 2022 (At Last)

/Planning drama activities that maximise student learning

The workshop by Danielle Miracle at the DramaWest Breath Conference provided a clear case for the need for drama teachers planning to link planning with stated student learning outcomes as set out in the mandated syllabus. The people around the table nodded wisely about the concepts of providing students with clearly articulated roadmaps for learning that made the connections with the syllabus. They seem in synch with the concepts of working from the “Big Picture”, using the “Scope and Sequence” providing a step by step “Layering of concepts progressively becoming more complex” (a “Spiral Curriculum”, though the term was not used) and ensuring that students were explicitly told the “Metalanguage” of the curriculum.

The workshop presenter then asked each group to work with a specific year group, specific syllabus, and talk through planning a unit of work. In doing so, she outlined how in her teaching in the UK, this sort of planning was linked directly to the teacher’s KPIs – Key Performance Indicators – and that your employment depended on planning delivering results. Schemes of Work are not just paperwork but accountability documents. That’s a significant shift in thinking about assessment – assessment and planning is usually considered as being about student achievement. On the other hand, this approach flips the focus to being on assessment of planning being about teacher performance. That clear sense of consequences is maybe something that is not built into local teaching in such clarity.

The group at my table began well: they identified that they would work with Year 10 and the form Youth Theatre. They added that they wanted to work with Brecht (foreshadowing the Upper Secondary course). They also agreed that the end point of the teaching unit would be a focus on a performance for a specific audience.

But the issue was: how to bridge the gap.

What are the steps - the layering of activities to get from the start to the end point?.

As I listened to the silence and the metaphoric shrugging of shoulders, it occurred to me that there was more fundamental issue: is there a lack of sufficient detailed knowledge about the form and the focus on Brecht. Teaching about Brecht has been simplified into a sort of shorthand: politics; a-Affect (because we don’t know how to say verfrumdungseffekt), don’t get emotional (not Stanislavsky), use posters/ captions/ placards, use song and dance, minimal sets, break the Fourth Wall.

They are valid points.

You can also do a quick scan of the Internet and find examples.

But how do you build connected teachable moments that at the end of the unit, leave students with enduring understanding to be able to apply Brechtian principles to their own drama creations?

Some ideas that might help with more detailed planning for this project

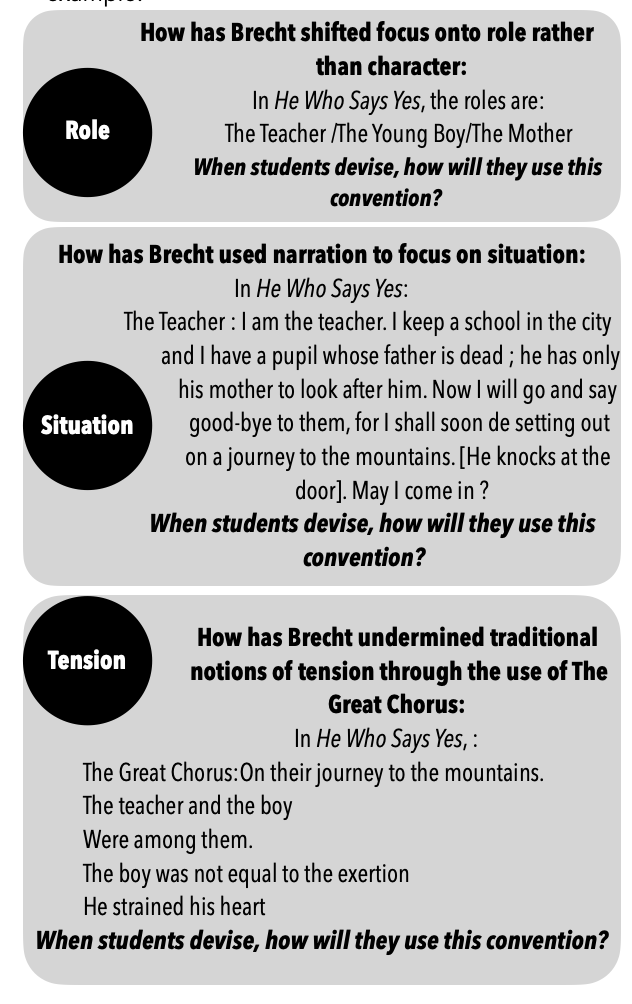

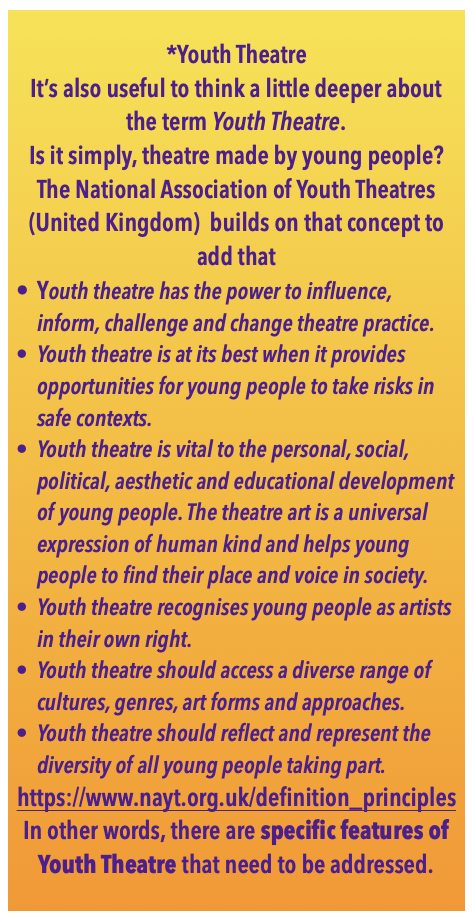

Brecht wrote a series of Lehrstücke. They would serve as useful role models for students. Working with plays such as He who says Yes and He who says No juxtaposed companion pieces side by side enables students to see how ideas are set up in dialectical oppositions. By looking at these as examples, we take the concept of some of Brecht’s ideas from the abstract to the specific – and particularly link to the concepts of Youth Theatre*.

Link the planned learning to the concepts articulated in the Syllabus. For example, it would be possible to build a layered exploration around the concepts of role, situation, tension, symbol, space, time (see the Elements of Drama identified in the syllabus). For example:

How could you build on these ideas?

How could some “Backward Planning” help?

State specifically what you want students to show in the Youth Theatre project as a result of your teaching in the unit. In other words, not a generalised objective but a specific one: in this Youth Theatre project students will show collaborative planning in generating ideas, applying specific principles of Brechtian practice including …

But it is important to also step deeper than just this one unit of work.

How do we respond to these questions?

How do we help drama teachers build more specific knowledge about the forms and styles named in the syllabus?

How do we help drama teachers build beyond generalised telegraphed and sometimes half-understood markers of form and style? (How do they know more than the headlines about Brecht, for example, to being able to deliver the sort of detail implied by the shorthand of curriculum documents?

How do we shift notions of accountability?

Who is being accountable?

What is it that teachers are actually accountable for? And, why does this concept freak out some teachers?